Melbourne’s Public Art: From Burke and Wills with AC/DC

In one way or another, every city has a story like this.

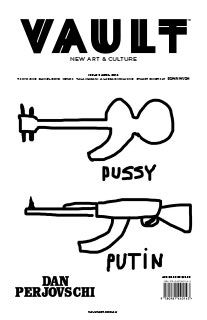

Image credit: Ron Robertson-Swann, Vault, 1978, prefabricated steel, 615 x 1184 x 1003 cm. Commissioned by the City of Melbourne, City of Melbourne Art and Heritage Collection

At the corner of Collins and Swanston Streets in central Melbourne is a mighty bronze sculpture by Charles Summers, which commemorates the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition through Central Australia. Unveiled in 1865, it has been shunted from one location to another, finally settling in its current site a couple of decades ago – but not before it was placed in the City Square with water cascading at its base. Someone must have twigged to the irony and eventually the water was gone. During its interregnum, it never made it to Royal Park – that’s where the expedition actually started out. Instead, there’s a precarious-looking cairn inset with a brass plaque.

Ron Robertson-Swann’s Vault – a great work of abstract formalism – was installed in Melbourne’s City Square in May 1980. A year later it was cast-off to a park. It had won a competition, an expensive one. The City Council got what it commissioned and decided to hate it. The controversy is now legendary, with boorish tabloid fervour dubbing it the ‘yellow peril’. In retrospect, it was an understandable, last-gasp expression in the wake of Australia ditching the final remnants of its White Australia Policy – interlopers not welcome – in 1973. It was also the year Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles was purchased and, of course, accompanied by hissy fits from the tabloids.

So why such a long gap between controversies? Why no fascination, let alone resistance, in what we don’t know and might eventually understand and develop a genuine affection for? Perhaps it’s because public art now has its wardens. Governments create bureaucratic, committee-driven commissions. The private sector has consultants. The results are usually as unimaginative as they are boring – tweely giving expression to a prescriptive brief.

The great American critic, Clement Greenberg (1909–1994), wrote an essay called ‘Avant-Garde and Kitsch’, which claimed modernism and the avant-garde was the bastion of taste and prevented art from collapsing into kitsch. But what happens when a reincarnated and faux avant-garde produces kitsch masquerading as something beyond its self-evident blandness? Yes, that’s much of Australia’s public art.

Australians remain largely uncurious about art, architecture and the built environment. We react to inconvenience, and only occasionally rail against artists. Usually it is architects whose work fails to lower its intellectual standard to that of the most dim-witted observer. Most public art is a sinecure for pre-set imaginations. The exceptions are rare, but quite wonderful when we find them.

By any stretch of the imagination, public art that is likely to make an enduring contribution to civic life is thin on the ground – or just above it (why do so many commissioners still think public art should be vertical?). Impeccably manufactured and large plonk art on a plinth, too, often becomes the demonstration of modest ideas writ large.

Melbourne’s much-debated Docklands development at the western edge of the city has public art as part of its community responsibility. It’s a mixed bag. Other nearby places like Yarra Boulevard and its bridges are also dotted with public art.

These sites raise serious questions about the very term ‘public art’. In itself, it suggests a reciprocity that ought to exist between the public and what’s commissioned. Part of this must be long-term public benefit. For centuries, great public art has defined ideas and moments in art history, revealing aesthetic greatness in every unfamiliar and radical permutation. What we tend to get now are designer affectations whose mystery ends when we read the accompanying text. The problem is not so much that the art is inherently bad, but that it’s unimaginative and humdrum – that there’s no compelling reason for it to have happened in the first place. Most are to the visual arts what Cuisenaire is to mathematics.

Sandridge Bridge is a cast iron heritage relic that crosses the Yarra River near Crown Casino. Most larger cities have ‘sculpture zoos’ (a term I first heard from British sculptor, Antony Gormley) at the edge of their CBDs. The Sandgate Bridge has a group of boldly declarative sculptures called The Travellers – 10 figures that represent migration to Australia since 1788 – spread across its span. It’s by an artist called Nadim Karam, who has never been exhibited in Australia and is unrepresented in all Australian public collections.

Each work represents a theme like “Melbourne Beauty – The Gold Rushes” or “Butterfly Girl – Asian and Middle East Migration”. It’s instructively corny. Memorialising history and its specific moments must inevitably be subordinate to the real experience it seeks to commemorate. There must be another way: to stop presumptuous egos unnecessarily interleaving with our daily experience. Exceptional talent is no longer a prerequisite. Discreet written, oral and pictorial accounts compete with well-intentioned, constructed magnificence that interrupts public places, sometimes wonderful vistas, too.

To strike a poignant register with history or contemporary experience does not necessarily require annotative three-dimensional oomph. David Moore’s Migrants arriving in Sydney (1966) is a 30.5 x 43.5 cm photograph, resonant in emotions of nervous anticipation and uncertainty. Or there’s a press photograph of Princes Pier – A friend gives Miss Clarice Faravoni a hand to welcome her fiancé LAC Ken C. Fisher on arrival at Princes Pier on the Athlone Castle. These are but two examples where modesty of scale and artistic intent easily surpass hyperbolic and permanent commemoration.

Australia has a fabulous history of exaggerated bigness. If we think of popular bigness, regional emblematic forms like Nambour’s Big Pineapple or the Big Banana at Coffs Harbour spring to mind. They have no inherent nobility beyond banal grandeur and a knowing silliness. We regard urban public art as being in a different league, certainly a higher intellectual plane. Well, maybe – just. Much of it signifies nothing beyond the obvious, whose easy meaning reduces far too many commissions to immaculately fabricated unimportance.

The Big Bull near Wauchope, New South Wales was demolished in 2007. It was a massive cement Holstein bull and you could walk into it and visit the gift shop and a display about beef. John Kelly’s tonness-of-bronze sculpture, Cow up a Tree, is at Docklands. There are wordy accounts of its greatness and it garnered huge media attention when it was exhibited on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées. One imagines a cow up a tree in Paris might well have that effect. The cow is based on William Dobell’s war work as a camouflage artist, where he made fake cows, the iconography of the eucalypt and a flood. In the early 1950s, Nolan took photographs and produced a group of paintings of carcasses in trees on a visit to Central Australia.

There’s a fine line between humour and over intellectualised folly, which seeks to give a personal historicised account of Australia and its culture. No matter how much generosity one brings to its interpretation, it appears to us unmistakably as something wrongly relocated from a children’s playground.

Not far away, at 757 Bourke Street, is neon text that reads ‘ON THE BEACH’. It’s by Janet Burchill and is an unpretentious, intelligent work. The typeface and constructed frame subtly evoke the period from which the title is taken. Nevil Shute’s 1957 novel later became a film by Stanley Kramer, which was made on location in Melbourne. The declarative neon On the Beach (there’s no beach nearby) is also a well-worn Australian colloquial one-liner, sometimes a three-star coastal motel promotion. When it’s first sighted, its incongruity is not immediately apparent: but Kramer’s film is about lives in the wake of nuclear catastrophe.

Corporate collections and art for new commercial building projects are more plentiful than many people might realise. There’s loads of consultant-driven, corporate-looking art – cultural retirement homes for once high-profile names whose art no longer attracts critical interest.

Deutsche Bank is one of a few conspicuous exceptions, here in Australia and abroad. It collects, commissions and makes public the results of what is essentially a dispersed museum collection, assembled with the intellectual rigour of a public institution. GOMA in Brisbane is currently exhibiting a massive installation, Falling Back to Earth by Cai Guo-Qiang. It’s from Deutsche Bank’s collection.

Some recent commissions are like museum works in public places. Highpoint is a massive shopping complex a few kilometres northwest of central Melbourne. A new addition to the existing commercial behemoth has doubled its size. Kerrie Poliness is one of Australia’s most interesting artists working in the conceptual and abstract genre, and is best known for her large wall drawings. Here, she reveals that it is possible to cite something specific, but not allow it to collapse into an illustrative didactic. In eight vast wall drawings at Highpoint, her largest and most ambitious project to date, Poliness has taken the flow and rhythms of the local river, the landscape and its geological forms as her conceptual foundation and created works which can be read as autonomous in themselves.

It is commonly accepted that landscape design can be high art. The Italians, French, Japanese and Chinese have recognised this for centuries. In Australia, the created landscape in urban environments too often appears as a last thought necessity. Planter boxes edge entries to buildings, gaps in pavements frame perpetually undeveloped vegetation whose relationship with its surroundings is often out of kilter.

A Grand Arbour along South Bank, South Brisbane opened in 2000 and is a wholly synchronised ensemble of materials, form and flora. Designed by Denton Corker Marshall it is a one-kilometre walkway edged by steel tendrils and a canopy of exuberant bougainvillea. It is an expressive spine which intersects an entire precinct that is edged by a thread of commercial and cultural buildings and public spaces.

The new eastern precinct at the Australian War Memorial by Johnson Pilton Walker is, for all intents and purposes, an amenities precinct. It is austerely elegant, quietly monumental yet perfectly legible in its function and without a skerrick of affectation. There’s no attempt to compete with, let alone trump, the respected dominance of the adjacent building. It includes a memorial for National Servicemen, and it’s not a work of vertical triumphalism.

Public money is now firmly part of public art. Few complain, many should. It’s a hit and miss arrangement. Colloquial, folksy popularism versus so-called high art will inevitably cohabit public spaces. Stadia sculptural tributes to sporting greats in dark bronze placed religiously high on plinths – it’s not going away and even living legends look posthumous. At a distance, all that knotted frozen action reminds us of old black and white photographs of charred human silhouettes, victims of wartime bombings. And the endless legacy of 1960s anthropomorphic neo-abstraction – vertical silvery forms that look like big surgical instruments.

Interpreting memory from aspects of our own generation’s history is fraught. People’s relationship with historical experience is usually personal, often deeply so. Attempting a generic representation of events as artistic expression – on our collective behalf – seems a deluded indulgence.

When we watch AC/DC’s music video, It’s a Long Way To The Top (If You Want To Rock ‘n’ Roll) (1975), we see the band playing on the back of a tray-truck cruising down Swanston Street. It goes past the Town Hall where, in 1964, The Beatles waved to the adulation of a massive crowd. The truck moves on past the City Square, long before Vault was commissioned, or the Burke and Wills sculpture found its final home. On the other side of Swanston Street is the old Capitol Theatre, designed by Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marion. Next-door is the Buxton Building where Roberts, Streeton, McCubbin, Conder and others held their now celebrated 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition in 1889.

Recalling history happens in all sorts of unexpected ways, and triggers reflection, which is often unable to be encapsulated by clichéd memorialising.

AC/DC Lane, off Flinders Lane in Central Melbourne, is a narrow, gritty, graffitied, cobble-stoned alleyway. AC/DC had no connection with it. It’s like public art as the perfect readymade. Tourists flock to it because of what the ambience represents – bars and music. It evokes memories unencumbered by creative intermediaries.

Likewise, The Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial, and the tomb for an unknown Australian soldier. It contains his physical remains, which were removed from a cemetery in France and returned. It’s a tomb: that’s it. Anything more would be superficial and unable the match the emotional depth of the private thoughts of visitors.

If we believe public art has a value to civic life, we ought to cease vapid grandiosity and think more imaginatively about how we give expression to the things that are important to us. When we err with public art, we live with its consequences. At least public galleries have a storeroom.

Image credit: NADIM, The Travellers, 2006, stainless steel. Photo: VAULT Magazine

Image credit: A friend gives Miss Clarice Faravoni a hand to welcome her fiancé LAC Ken C. Fisher on arrival at Princes Pier on the Athlone Castle. Photo: Argus Newspaper Collection of Photographs. Courtesy State Library of Victoria

Image credit: Janet Burchill, On The Beach, 2007, neon. Image courtesy Lisa Blas

Image credit: John Kelly, Cow up a Tree, 2000, bronze, oil-based paint, 800 cm (overall height). Courtesy City of Melbourne Art and Heritage Collection

Image credit: Installation view Kerrie Poliness, Wave Drawings 1-8 at Highpoint Shopping Centre, Melbourne, 2013. Courtesy the artist

Image credit: South Bank Grand Arbour, Brisbane. Architect: Denton Corker Marshall, 2000

Image credit: A poster of Angus Young, AC/DC Lane, Melbourne, 2010. Photo: Nick Carson

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 6

Click here to Subscribe