Naked By the Window: Mythologising the Highs, Lows, Lives and Deaths of Artists

In the wake of revelations dispelling conventional wisdom on the death of Van Gogh, VAULT explores our want to speculate on the lives and deaths of art’s most famous figures.

Image credit: Vincent Van Gogh, Self-portrait with bandaged ear, 1889, oil on canvas 51 x 45 cm

Call it ‘art world biographical mythology’, or just call it ‘the goss’ – either way, our fascination with the lives, loves and deaths of artists has never been keener.

Renaissance artist, writer and architect Giorgio Vasari called his insider account of the Renaissance Lives of the Artists and gave us everything from Uccello’s fear of melted cheese, to Leonardo da Vinci’s myriad practical jokes, which included frightening his visitors by gluing wings on to lizards, and using bellows to inflate the intestines of a cow in the room next door.

Closer to our own times, we are told in Geordie Greig’s wonderfully readable book Breakfast With Lucian that Lucian Freud painted Kate Moss naked, that infamous English gangsters the Kray twins threatened to cut off his painting hand over bad gambling debts, and that he was officially recognised as father to 14 children by numerous partners (three were born to different mothers within a few months of each other), but the unofficial tally could be as high as 40!

Jorg Immendorff, the German Neo-Expressionist painter, also put it about a bit. Only his friendship with German Chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder, saved him from jail when he was caught in what the European press called, “The Orgy of the Year”. As London’s Independent newspaper reported at the time, “Police discovered Mr Immendorff lying naked on a bed, surrounded by nine prostitutes, in a suite at Dusseldorf’s Steinberger Hotel. In a Versace ashtray on a bedside table, and in the artists’ atelier nearby, 21.6 grams of cocaine were found. Officers had been tipped off by a prostitute who had apparently been rejected. The artist admitted holding 27 other similar cocaine parties over 30 months.”

What Australia’s Adam Cullen got up to in hotels in not well known. However, he has the rare distinction of having The Cullen Hotel in the inner Melbourne suburb of Prahran named after him. You can wander around inside and see almost every piece of available wall space decorated in his trademark primary colours, or you can hire a Smart Car for a day ($50) and drive around town with a Cullen painting of a policeman on a donkey airbrushed onto the door panels. For a real taste of his ‘abject survivalism’ (The Cullen Hotel’s entertaining website uses his quote, “Endurance is more important than the truth”) Erik Jensen’s tell-all biography Acute Misfortune is the go-to book for the enduring tales about pigs’ heads, shooting incidents, motorbike rage and pharmaceutical abuse. In one of Jensen’s early chapters, he quotes Cullen, ever the self-mythologiser, as saying, “Everyone loves a car crash, but they stare at a safe distance. I get up close.”

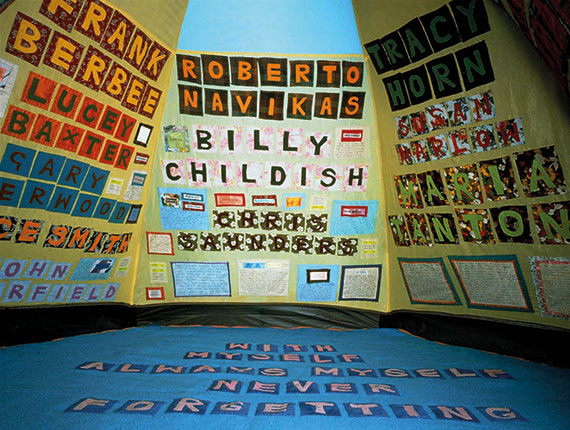

On the other side of the world, Tracey Emin gave us a tent embroidered with the names of Everyone I’ve Ever Slept With (including her mother and grandmother, amongst the laddish mix of lovers and abusers in Margate and London), while American Pop painter Larry Rivers’ memoir What Did I Do? – billed as an “Unauthorised Autobiography” – is described by Publishers Weekly as “exuberantly hip and sexually freewheeling, [it] displays his relentless, almost exhibitionistic candour… Born in 1923, he was raised in the Bronx by a hypercritical mother and a father reportedly guilty of bizarre sexual improprieties with children. A bebop jazz saxophonist with a heroin habit, Rivers abandoned his first wife and their sons in 1947. He later married his Welsh housekeeper, a ‘deliciously unique female’… Rivers is most emotive when discussing his ‘romantic fling’ with poet Frank O’Hara.” He also brings an artist’s inventiveness to his many extreme forms of teenage masturbation.

So much for the mythologising of sex and drugs. Where things get really interesting, and dangerously speculative, is when we turn our attention to death, suicide and murder. Erik Jenson begins his aforementioned memoir of Adam Cullen with the sentence, “Coffins weigh more than you expect”, and it is a good way into the book and to the topic of ‘death and the artist’ in general. No doubt it will enter the listings in Books: One Hundred Great First Sentences. I

n its December 2014 issue, Vanity Fair rekindled a several-years-old proposition that Van Gogh did not in fact kill himself, but was murdered by two local schoolboys. The nub of the story is that he took a fall for them, so that they would not be tried for his injury and death. The two authors, Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, had already won Pulitzer Prizes for their earlier biographies, notably that of Jackson Pollock, so they came with recognised investigative talent and some art historical authority. And this was no rushed job. The two men spent over a decade visiting and revisiting the Van Gogh Foundation archives in Amsterdam. They were given access to all his letters, and made copies of everything to take away for translation.

“Van Gogh himself wrote not a word about his final days,” they write. “The film [Vincent Minelli’s Lust for Life] got it wrong: he left no suicide note – odd for a man who churned out letters so profligately. A piece of writing allegedly found in his clothes after he died turned out to be an early draft of his final letter to his brother Theo, which he posted the day of the shooting, July 27, 1890. That letter was upbeat – even ebullient – about the future. He had placed a large order for more paints only a few days before a bullet put a hole in his abdomen. Because the missile missed his vital organs, it took 29 agonising hours to kill him.”

René Secrétan was the 16-year-old ringleader of a group of lads that would taunt and tease the misfit artist living in the midst of the town of Auvers, outside Paris. He was a bully who hero-worshipped Wild Bill Cody, dressed like him in buckskin and cowboy hat, and bought himself a pistol. He’d seen the cowboy’s travelling stage show in the capital just the year before. “René let Vincent eavesdrop on him and his friends when they imported ‘dancing girls’ from Paris,” the authors write. “He shared his pornography collection. He even posed for some paintings and a drawing. Meanwhile, he conspired with his followers to play elaborate pranks on the friendless tramp they called Toto. They put hot pepper on his brushes (which he often sucked when deep in thought), salted his tea, and sneaked a snake into his paint box.”

Would they go as far as to shoot him? Perhaps. The shot was to the middle part of the body, not a potential suicide’s first choice. And all the talk about suicide was apparently stirred up by the rival painter Émile Bernard in a letter to a critic he was trying to impress.

The myth of Van Gogh’s suicide was so strong that few people at the time of publication would take seriously the notion of their favourite tortured artist having been murdered. The Vanity Fair article can be read online and it updates their research through the reflections of one of the world’s leading forensic experts on gunshot wounds, Doctor Vincent Di Maio. His conclusion (spoiler alert) is that, “It is my opinion that, in all medical probability, the wound incurred by Van Gogh was not self-inflicted. In other words, he did not shoot himself.”

So there we are. It will probably forever rest in the liminal area of ‘what ifs’.

There is also another myth-busting theory doing the rounds that Van Gogh did not cut his ear off, but lost it in a duel with Paul Gauguin, with whom he had set out to build a utopian painters community in the South of France. Gauguin himself has his own fair share of myths circling like coffin flies. There’s the one about how he tried to commit suicide in Tahiti by drinking arsenic on top of a hill, but became so ill that he spewed it all up and survived. What if, I’ve often wondered, Gauguin had committed suicide and Van Gogh had survived that gunshot? How differently would we then read the lives of both artists?

My own favourite contemporary tale of art and murder, brilliantly described by Robert Katz in his page-turner of a book Naked by the Window, describes the death of artist Ana Mendieta when she fell from the balcony of sculptor Carl Andre’s 34th floor apartment in Manhattan. They were married, kept separate apartments and had been heard having a blazing row shortly beforehand. It begins like a Lawrence Block crime thriller: “Mike Connelly and his partner John Rodelli had been working the Henry-Ida sector of Greenwich Village that hot and muggy, and unusually quiet, Saturday night, when at five-thirty Sunday morning, September 8, 1985, they got a call about ‘a jumper down at 300 Mercer Street.”

It concludes with the trials and re-trials of Carl Andre for Mendieta’s murder. And at the beginning of the book, as if it is a play, there is a list of characters. So divided did the art world become over this scandal that the personae are divided into “Ana’s Friends” (Dotty Attie, Leon Golub, Sol le Witt, Nancy Spero, and many others) and “Carl’s Friends” (Claes Oldenburg, Barbara Rose, Frank Stella, and Lawrence Weiner).

And one of the first steps in the mythologising of this terrible event was in the late 1980s when the Dutch collective of Superfiction artists known as Seymour Likely produced a floor piece called Never Marry a Railroad Worker (Carl Andre once had such a job). Modelled on Andre’s Equivalent VIII (a work that provoked so much ire when bought by the Tate Gallery), instead of being neat rows of firebricks (120 in a cuboid shape), it was made up of a similar number of books designed to look like a Gideon’s Bible, but with blank pages, and the name Seymour Likely on the cover. The mythologising had begun.

Image credit: Adam Cullen Smart Car Cullen Hotel, Melbourne. Courtesy Art Series Hotel Group

Image credit:

Adam Cullen, Kelly Hunter, 2009, relief print, 70 x 70 cm. Edition of 30.

Courtesy Michael Reid, Sydney

Image credit: Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, 1995, appliquéd tent, mattress and light, 122 x 245 x 214 cm. Courtesy the artist and White Cube, London

Image credit: Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (detail), 1995, appliquéd tent, mattress and light, 122 x 245 x 214 cm. Courtesy the artist and White Cube, London

Image credit: Vincent Van Gogh, Wheatfield with crows, 1890, oil on canvas, 50.5 x 103 cm. Courtesy Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 10.

Click here to Subscribe