Sally Smart: Piece by Piece

The output of prolific South Australian-born artist Sally Smart is a study in the radical nature of cutting as well as the poetry of moving parts.

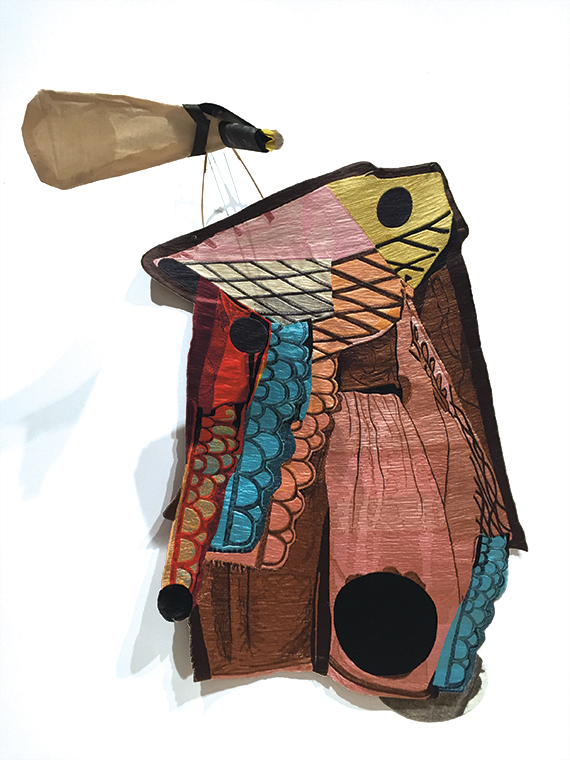

Image credit: Sally Smart, Assemblage Embroidery #5 (Sonia), 2016, synthetic thread and collage elements, 109.2 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York

We talk on the phone the day after Sally Smart arrives home from New York. “A lot of my practice has been pin, un-pin; pin, un-pin,” she explains. In her warehouse studio in North Melbourne, three long walls are dedicated to pinning, and a wooden floor has been installed over the original concrete to allow for comfortable movement as her private choreography unfolds. As with most studios, there is the necessary storage and office space, and the ongoing negotiation of “getting out of the office and into the studio…you do have to be a bit strict about that.” Smart describes working with ‘elements’ — the swathes and fragments of materials including fabric, paper, canvas and felt that make up her installations. “I have this constant [need] to work [with] the elements — rehearsing, constructing and documenting them,” she says.

Smart assembles, disassembles and reassembles these elements until they form assemblage images that occupy the boundary between rough and resolved. Over the years, her materials have been cut and pinned to walls in the form of pirate ships, human figures, trees, plants and furniture. Threaded through these tangible materials is a matrix of concepts, philosophy and politics developed throughout 30 years of artistic practice. These include choreography and movement, identity and history, and the theories and psychology of cutting. Once Smart is satisfied that the aesthetics and theories are perfectly tuned and attuned, each installation is packed up and shipped off for installation. At the time of writing, she is in the midst of a solo exhibition in New York and has just wound up a two-person survey with Entang Wiharso at the Galeri Nasional Indonesia.

The investigation of collage has been a constant throughout Smart’s career. Rather than simply anchoring her collages onto a traditional support like paper or canvas, Smart’s preference is to pin large-scale fragments directly onto gallery walls. Although each element is decisively placed, the effect is a sense of ephemerality, and no two installations are ever exactly the same. Smart’s compositions are a conversation with the floor, doorways, fixtures and ceilings of each space, and she has described her collages as being always “one pin away from changing.”

The act of cutting is implicit in collage. For Smart, this means cutting into a range of materials, each with its own distinct texture, density and resistance. Cutting can be a loaded act, and Smart refers to ‘the politics of cutting’ when talking about her work. Cutting is decisive and irreversible, and is at once destructive and constructive. It is divisive, in that a previously whole piece of material is fragmented. Equally, though, it is generative: multiple parts are created from a single whole. Psychiatrists coined the term ‘delicate cutting’ in the 1960s to describe a kind of self-harm that, according to research, was most prevalent in young, attractive women.2 The paternalistic implications of this term — wherein self-harm is gendered and made to sound quaint, feminine and decorative — appear to be countered in Smart’s work. The artist that cuts is an active agent, transforming the world rather than passively depicting it.

Smart’s process is made manifest in her series The Choreography of Cutting, which has been shown in various iterations since 2013 in Sydney, Adelaide, London, Canberra, Jakarta and New York. The centrepiece is a long, black-painted wall covered in a matrix of scrawled notes, arrows, string and taped fragments of cut paper and a video monitor. In one sense, it is quite academic, pedagogical even: the wall is a research tool, bearing the names of artists, choreographers and theorists; artwork titles; quotes and fragments of poetry; lists of techniques and actions. In another sense it is personal and intimate, as if we are entering the artist’s mind, with its moments of chaos, intensity, confusion and epiphany.

Smart’s influences are spread across this Beuys-esque blackboard, mapping the trajectory of her practice and placing herself in concert with those who have informed her work over the years. She researched choreographic notation, and found that where an artist may make a preliminary sketch on paper, the choreographer sketches a movement with their body in space, making the final notation when they are satisfied that it is perfect. Historical links were found between Laban’s system of choreographic notation, educator Rudolf Steiner, Dada luminaries Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hannah Höch, and avant-garde choreographers Pina Bausch and Martha Graham. The blackboard reveals connections between collage and choreography, cutting fabric and cutting space.

These artists crop up again and again for Smart, and threaded throughout these Western influences are references to Javanese wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) and the work of contemporary Javanese textile artisans. Exhibited alongside the blackboard are works that combine these two worlds: Smart’s Ballets Russes assemblages. She has digitally cut up the costumes created by Picasso, Matisse, Delaunay and others for the Russian Ballet between 1909 and 1929. This imagery is then recreated in embroidery by Indonesian artisans, and the final pieces are assembled by Smart, incorporating various collage elements including metal and cane. The resulting works approximate bodily shapes but could never actually be worn. As a result, she vividly recreates the tension between artistic vision and functionality that dogged the Ballets Russes costumiers.

Multiple trips to Indonesia over the last three years, including a residency at Entang Wiharso’s Black Goat Studios through Asialink in 2015, have enabled Smart to engage in ongoing cross-cultural discourse. This has played out most recently in Conversation: Endless Acts in Human History, a two-person survey featuring Smart and Wiharso. Its first iteration, in early 2016 at the Galeri Nasional Indonesia in Jakarta, was an organisational and curatorial collaboration between the artists. Smart suggests that creating work together could have been a simple proposition, but that working together to stage the show — going through each others’ back catalogues, liaising with curators and gallery staff — led to fascinating conversations, collaborative problem-solving and enriched cross-cultural understandings.

The experience of growing up in an isolated pocket of South Australia underpins Smart’s significant European and Asian influences. In earlier works, including Shadow Farm (2001), Smart depicted this rural setting through her typically ghostly, notational silhouettes. Generally, though, her subject matter is outward looking: the history of female pirates, the Ballets Russes costumes and the history of choreographic notation. Smart’s early geographical isolation perhaps goes some way to explaining her independent research drive, and this desire from early on to link in with a broader international discourse. She describes, incredulously but proudly, trying to track down information on Höch before books on her work were even published in English, let alone available in Australia.

Smart sent me images of past work including a full-length portrait; hands curled around the control bars of a marionette. The doll, made by the puppeteers at the University of Connecticut where Smart was artist-in-residence in 2012, is a veritable doppelgänger of Smart at one-third scale: same fire-red hair, long black dress and pale green Mary Janes. The facial features of Smart’s doll are exaggerated, the skin more pallid, but it is unmistakably her. She tells me that Albert Einstein had a puppet of himself made by the Yale puppeteers. “You can take that however you like in terms of my motivations!” she says. This uncanny dual self brings to mind the binaries of private and public identities; what we choose to reveal and conceal. In public we perform proxies for our ‘real’ or total selves, and I imagine that this doll could be a way for Smart to be present without revealing too much. As if confirming my theory, Smart explains that the puppet was a secret project, and she surprised a Connecticut symposium audience with its arrival in her stead.

With her career focused increasingly on the international circuit, Smart admits that working out “where I want to put my energies, in which parts of the world, and where I want to live, where I want to be, and when I need to be there” is a work in progress. She is an Honorary Senior Fellow at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, so wherever she ends up, her links to Australia will remain strong. The limits of space and time may mean that Smart’s puppet-doppelgänger makes an appearance

for her from time to time. A surrogate for her own body,

a fragment detached and dislocated at once.

Sally Smart, Choreographies (The Artist’s Ballet) continues at Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert until May 23, 2021.

The following events coincide with the exhibition:

Artist Talk, May 14, 2021, 10AM – 11AM & 4PM – 5PM

In Conversation: Sally Smart and Rachel Kent at the MCA May 15, 3PM – 4PM

Sally Smart, The Artist’s Ballet continues at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney as part of The National: New Australian Art until August 2021.

Sally Smart is represented by Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert, Sydney, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne and Postmasters Gallery, New York

gallerysallydancuthbert.com

sarahscoutpresents.com

postmastersart.com

Image credit: Sally Smart, Pedagogical Puppet (Self Portrait), 2012 digital photograph, 203 x 111 cm. Courtesy the artist, Postmasters Gallery, New York and Galeri Nasional Indonesia, Jakarta

Image credit: Sally Smart, Assemblage Embroidery #3, 2015–16, synthetic thread, pins and collage elements, 121 x 91 x 31 cm. Courtesy the artist, Postmasters Gallery, New York and Galeri Nasional Indonesia, Jakarta

This article was originally published in VAULT Issue 14, MAY 2016.

Click here to Subscribe