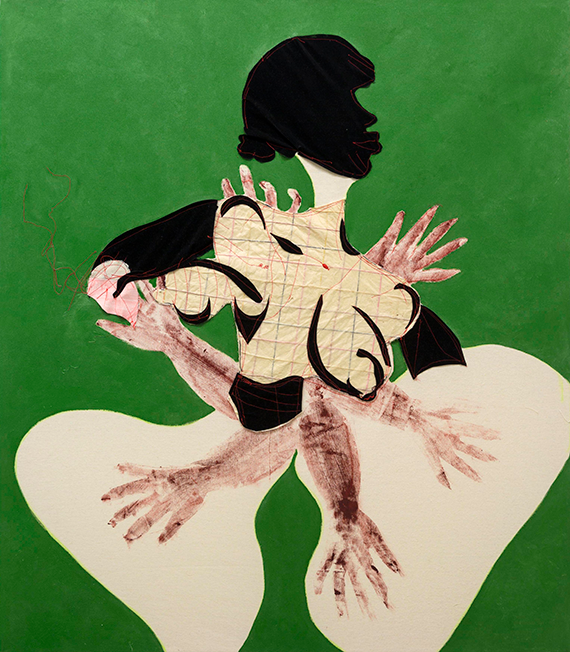

Tschabalala Self: Bodily Pleasures

Undulating with joy, power and erotic energy, the mixed-media paintings of American artist Tschabalala Self ingest the fantasies that cling to Black female bodies before exploding them from the inside out.

Image credit: Tschabalala Self, Get’It, 2016, acrylic, Flashe, handmade paper and fabric on canvas, 243.8 x 182.8 cm. Courtesy the artist, Thierry Goldberg, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

In March 2016, Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self held a solo show at Naples institution T293. It was Self’s first exhibition in Italy – the culmination of a residency – and it centred on the idea of a house party: a squelching, bubbling, ebullient space populated by multiple bodies and infinite interplays of gazes. Collages, paintings and sculptures commingled to forge a series of tableaus, in which exaggerated, prismatic characters looked at themselves and allowed you – or instructed you – to look back.

One work stuck out, to me at least. Get’It was a large painting that took over half a wall, its backdrop engulfed in a hypnotic, verdant green. In the centre of the canvas was a Black woman in profile, arms coolly tucked into what looked like the pockets of cream-coloured trousers, ballooning outward from her hips to gargantuan proportions. Emitting from her core was a writhing, energetic mass of body parts. Six hands and forearms splayed outward like a demi-god, their thirty fingertips touching strong, wide thighs and extending past her neck, reaching further out as if uncontained by the painting. They felt like a spinning wheel. They felt like a freeze-frame. They felt like a dance in slow motion.

On first reading – especially for those unfamiliar with Self’s work – these multiple hands might be confusing. You don’t know what you’re looking at, or the best way to look. Is this woman being touched, or doing the touching, or both? Spend more time with the painting and the inbuilt gender biases fade a little. Self’s women are not meek or unaware, not slapped or smacked without permission. They are a spectacle because they choose; they’re also too slippery to overtly pin down. Speaking to VAULT via telephone, the artist confirms Get’It’s woman is dancing, caught mid-movement, that every hand is likely her own. “It’s a painting that depicts someone touching themselves, and in doing that there’s the potential of being touched by another,” says Self. “It becomes a conflation of those three ideas: the freedom to move, that freedom turning into a decision to touch herself, the possibility [she’ll] allow someone else to touch her too. All those ideas centre on the character’s pleasure and her agency within her own body. I want people to think in a more complex way about sexuality and touching and performativity around the female body. Because a woman is allowing her body to be available, or to be seen, you have to allow the possibility that she is in control of the situation.”

Three months later, at Kate Werble Gallery in New York, Self took part in the smart, self-reflexive group show, Sexting, which examined our growing dependence on smart-phones and the ways they relate to sex, sexual self-portraits, our own bodies. Alongside works by Melanie Schiff, Burt Barr and Sarah Wright, Self presented Big Red, a deliciously garish wooden sculpture that looked like a giant cardboard cut-out, with its cartoonish legs and rounded buttocks and the explicit curves of a vagina. One leg was propped against the white wall, the other extended out into the gallery, forcing the audience to reroute their path, to consider the half-body as they moved. “Hello!” it shouted. “I am busy! I am having fun!” The detached legs were painted red all over, in bright acrylic spray. Self believes this hyper-charged hue was vital to the work’s success: “I wanted to achieve that kind of aggressive presence in the space. That shape, I would say leans toward a ‘feminine’ body type, even though I think there are elements of it that are gender non-conforming. I wanted it to be flamboyant, happy, taking up space in the gallery. The colour helps communicate some of that authority, that desire to be looked at.”

Get’It and Big Red are denotative of Self’s broader practice, which employs various techniques (painting and collage, sewing, binding, drawing, sculpture) to depict the Black female body in states of pleasure, both sexual and non-sexual. Her partially fragmented characters – sometimes pictured with lovers – are painstakingly made from drawings, then built up with swatches of fabric and ink, from paint and imprints of hair. They strut, sneer and smile. They finger themselves. Sometimes they look right at the audience, if only to remind us how our voyeurism plays out. Kate Sutton of Artforum describes Self’s distorted, swelling body parts acutely: they are “an army of swooning calves, nipples like ten-galleon hats, and pussies like peach pits amid voluminous hips.” These avatars – as Self is prone to call them – absorb tropes imposed upon the Black female body and they deflect them, all at once.

Since graduating from Bard College in 2012, and later, from the Yale School of Art in 2015 with an MFA in Painting/Printmaking, Self has been steadily preoccupied. In 2016 alone, there were two solo shows and 13 group exhibitions; for her solo show at Sydney’s COMA Gallery this year she’s hoping to present sculptural and two-dimensional pieces. She questions herself constantly, honing in on conceptual weak points from old work, finding formal elements that could be pushed further. “Am I communicating something that’s helpful, healthy and new? Most importantly, something that’s sincere? There’s a lot of noise that’s in my head, in the heads of Black artists. You have to be really on top of yourself not to let that noise drown out your true intentions… considering the political climate, this is not a time to be conceptually lazy about your work – so much more is at stake.”

What Self’s work attempts to redress is the lack of mainstream imagery and intellectual space given to promoting Black love: affectionate embraces, families, images of the body that are erotic but not sexualised, that aren’t synthesised or flattened. “There’s a huge disconnect as to how the average person of colour – probably all people of colour – visualise and imagine themselves, and how they are depicted to everyone else, how they’re consumed by everyone else,” Self says. “People are looking at you in a very colonial, voyeuristic way, looking at you as being other and as one that can be possessed and understood… At some point, people of colour start to reproduce the same kinds of images of themselves. People only have so many ways of communicating basic ideas. If the idea of blackness – in terms of iconography – [is reduced] to images of degradation and over-sexualisation, to a white gaze, when people attempt to communicate ideas of themselves, they’ll unfortunately sometimes default to the normative, because it’s the fastest way to get the message across, even though it might not be the most sincere or accurate.”

Tschabalala Self, By My Self at the Baltimore Museum of Art continues until September 19, 2021.

Tschabalala Self is represented by Pilar Corrias, London and Eva Presenhuber, NYC.

artbma.org

pilarcorrias.com

presenhuber.com

tschabalalaself.com

Image credit: Tschabalala Self, Untitled, 2016, fabric, Flashe and acrylic paint on canvas, 142 x 162 cm. Courtesy the artist, Thierry Goldberg, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

Image credit: Tschabalala Self, Big Red, 2016, acrylic spray paint and Flashe on wood 121 x 177 x 2 cm

Image credit: Tschabalala Self, Sapphire, 2015, oil and pigment on canvas, 84 x 60 cm. Courtesy the artist, Thierry Goldberg, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 18 (April – June 2017). Click here to Subscribe