Tony Albert

On Being Seen

As Tony Albert’s survey Visible concludes at Queensland Art Gallery, VAULT examines his career to date.

My first studio visit as a young arts professional was approximately 10 years ago with leading Australian artist Tony Albert. I was an undergraduate student at the time, I had seen the artist’s work in galleries prior to the visit, and I remember feeling excited about meeting the artist in his West End studio in Brisbane. I gazed around the space looking at works and materials in various stages of production as Albert shared his experiences of art and life with us. He commented on various aspects of his practice, focusing on the challenges of operating in the art world as an urban First Nations artist. As a non-Indigenous Australian who was just beginning to enter the contemporary art industry, I greatly benefited from this early exposure to First Nations art and I was grateful to Albert for his generosity and candour with us that day. Today, Albert’s studio has grown in size and is now based in Carriageworks, Redfern, Sydney, but his ability to openly communicate challenging issues to a wide audience has not changed.

It is apparent that Albert has had a relatively quick rise to fame, and this success can be attributed not only to the work itself but also to Albert’s deeply embedded role

in the arts. Since his undergraduate days,

he has continued to have a strong connection to community, through platforms such as Brisbane’s Indigenous art collective ProppaNow, and through his mentorship by Brisbane-based senior artist Richard Bell. These beginnings set the artist up with a strong founding base to then go on to major exhibitions, residencies and awards. Some of these recent achievements include being awarded the 2014 Basil Sellers Art Prize and the 2015 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award. In 2015 his major public artwork YININMADYEMI Thou didst let fall (2015) was commissioned to commemorate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who had served in the Australian Army, and was erected in Sydney’s Hyde Park. Following on from this in 2016, he won the Fleurieu Art Prize. Alongside these awards, Albert has been engaging in other aspects of professional development including a residency at the International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP) in 2015, and Asialink’s 2014 Arts Residency Laboratory in Artback NT in Alice Springs and Cemeti Art House in Yogyakarta.

Visible, curated by Bruce Johnson McLean, Curator, Indigenous Australian Art at QAGOMA, is the culmination of the last 10 to 15 years of Albert’s practice. This exhibition marks the artist’s career trajectory, and is placed in conversation with newer commissions by Albert for the exhibition. As the title suggests, Visible is engaged with themes surrounding identity politics for First Nations Australians,

and the exhibition has a strong focus on the role of young Aboriginal men in particular. Albert was born in Townsville in 1981 and was raised in Brisbane; he identifies as Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku Yalanji First Nations peoples. Albert is known for his commitment to hard-hitting, politically charged works and exposure of histories and present-day realities for Indigenous Australians. His work is communicated through a range of media including text-based sculptures, installation, film, photography and community projects.

The exhibition includes a slew of the text-based works for which Albert is well known, including Sorry (2008), Headhunter (2007) and whiteWASH (2018). Each of these works is large in size, constructed from matt black text backgrounds layered with collaged Aboriginalia, creating another physical and metaphorical layer to the works. In an online interview with the artist on QAGOMA’s website, Albert elaborates on the work Sorry (2008).

He explains that the work was originally commissioned by QAGOMA on occasion of its exhibition Optimism (2008–2009). It was made by the artist in response to the Australian government’s 2008 apology to Australia’s Indigenous people, made by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. However, since 2008 Albert has actively reflected on the role of ‘the apology’ and what he describes as a lack of follow-through by the government in creating real change in Indigenous policy. In light of

this for Visible, he has changed the format of the work so that the text ‘Sorry’ is displayed in reverse. Through this inversion of the text Albert highlights the insincerity of the statement.

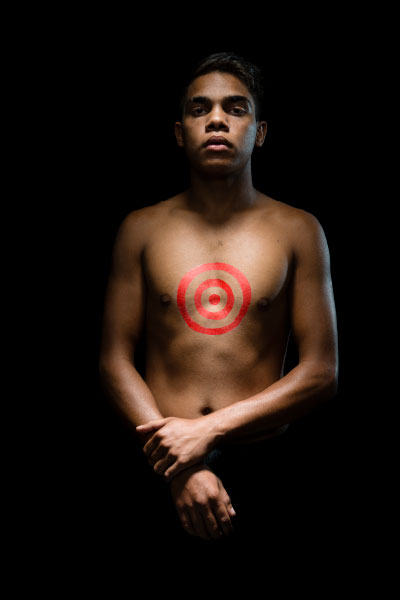

Visible also includes the recent photographic series called Brothers (2013), which depicts 25 photographs of young Aboriginal men who have been inscribed with certain marks or targets on their chests. Albert explains this work was a response to a 2012 police brutality incident in Sydney’s King Cross, and the subsequent protest that followed the act. This work is a visual response and almost a memorial or homage to the protest marks that were self-inscribed by young Aboriginal protesters that day. A more recent extension to this series is the work Moving Targets (2015), which explores the same issues through a multimedia approach. The work is a large installation featuring the shell of a battered car. Inside the vehicle, screens display a dance piece that reflects and refers to the 2012 incident. This work was co-produced with Bangarra Dance Company Theatre Director Stephen Page, and is a sobering, yet rich visual experience. Other highlights of the exhibition include the artist’s extensive collection of Aboriginalia (collected from 1988 to 2018) exhibited in a grand salon-style hang, featuring an array of kitsch objects, from a pinball machine centrepiece to other items such as cups and tea-towels. Through these accumulated pieces, Albert brings attention to the racist histories of offensive ‘folk art’ and instead actively reclaims them as his own.

Albert actively draws from his success as an artist to lift others up with him, and his collaboration We Can Be Heroes with the children of Warakurna is further evidence of this. This project is QAGOMA’s Children’s Art Centre’s project, and is a series of works that are co-presented by children from Warakurna, a remote Aboriginal community in Western Australia. We Can Be Heroes includes the photographic series Warakurna – Superheroes (2017) and a series of paintings featuring Mamu, a spirit found in Warakurna. At the media preview for his exhibition, Albert explained that he had invited the children from Warakurna to the exhibition opening, and furthermore, he had ensured that they were actively remunerated and credited as co-producers of the work.

In Visible, we witness Albert’s agile combination of ongoing commitment to practice, placed in conversation with meaningful community outreach. The topics he covers in his work span from the collective to the individual; it is an exhibition with pointed politics yet with an approachable attitude that assists the artist in connecting to a wide audience. Reflecting on my early studio visit with the artist, it is apparent that his openness to discuss the issues that matter to him with a range of people is a strength that will see Albert called upon again and again to call for change in contemporary Australia.

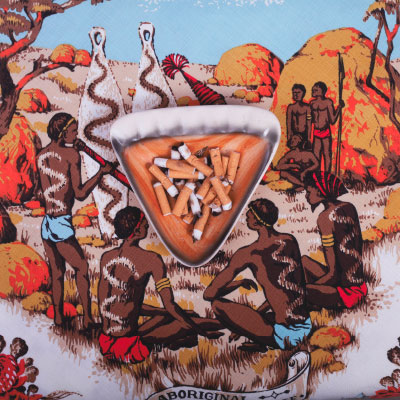

TONY ALBERT

Boomerang and Spears (from Mid Century Modern series), 2016

pigment print on paper

100 x 100 cm

TONY ALBERT

Ceremony (from Mid Century Modern series), 2016

pigment print on paper

100 x 100 cm

TONY ALBERT

whiteWASH, 2018

vintage ashtrays on vinyl lettering

dimensions variable

TONY ALBERT

Brother (Our Past) (from Brothers series), 2013

pigment print on aluminium with

acrylic paint

150 x 100 cm

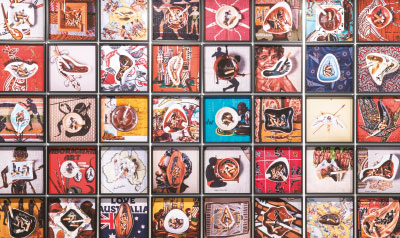

TONY ALBERT

Mid Century Modern (series), 2016

pigment prints (24 works)

100 x 100 cm (each)

TONY ALBERT

Headhunter, 2007

synthetic polymer paint and vintage Aboriginal ephemera

110 x 370 cm

Courtesy the artist, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

... Subscribe