Arlo Mountford – The peasants are revolting

Peter Hill reviews the mid-career survey of multimedia artist Arlo Mountford

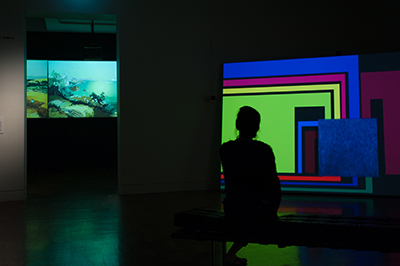

Image credit: Arlo Mountford, Deep Revolt, installation view.

Shepparton Art Museum, 2019. Image courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery Melbourne.

Photo: Emiliano Fernández

They are the signature motifs in Arlo Mountford’s extensive vocabulary of images and shapes. Flat, round-headed figures that look like they have escaped from a gender-specific toilet door, or a “green man” traffic crossing. They exist somewhere between the shock of early South Park and the banality of the Pack & Send courier logo. You don’t really realise how ubiquitous this figure is in Mountford’s work until you view his mid-career retrospective from start to finish.

The first work that you encounter is Portrait of the Artist as a Dead Man (2003), a vinyl adhesive emoji with crosses for eyes. When he made it – or rather, instructed a sign-maker to fabricate it – he was an artist-in-residence at Melbourne’s Gertrude Contemporary Studios. In it is found all the humour and violence, the simplification of forms and the expansiveness of vision, that marks his big-ambition art practice at all chronological points of its evolution. It is a good place to start.

Directly opposite this work is a series of album-sized circular vinyl paintings. They look familiar. That’s a Damien Hirst, and that’s a Bridget Riley, and with a little help from the room notes you locate a Marcel Duchamp. Each is identified only by the first name of the appropriated artist. The art-savvy viewer will quickly work out that Ugo refers to Swiss-born artist Ugo Rondinone, and Tanaka to Atsuko Tanaka from Japan. Mountford is playing games with us, and with the unfolding narrative of art history, as he has done with Bruegel and Andy Warhol before. His games cross continents as they do cultures and technologies. And as technologies advance so his art changes. The video animation is freed from being housed within a cube-shaped television and can now become a wash of colour across an entire gallery wall. The hand-drawn is usurped by the digital. But as Mountford remarked during his floor talk prior to this exhibition opening, “There is more hard labour involved when working with state-of-the-art technology than when working purely by hand.”

In an excellent catalogue essay, artist and writer Oliver Watts sums up the methodology of Mountford’s work when he says the artist “takes great joy in mashing up visual culture as a way of commenting on the contemporary world. Many of the videos begin with an art world conceit: commenting on the art historical canon; the place of the viewer within the gallery space viewing a gallery space; a joining of low and high culture.” This type of work is very much of its time and chimes perfectly with that of rising Scottish art star Rachel Maclean, whose Make Me Up (2018), aBBC-commissioned film she described to me in a recent interview as “a mashup of Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation (1969)series and RuPaul’s Drag Race.”

There is a satisfying narrative arc in this exhibition that takes us from Mountford’s 2003 Portrait of the Artist as a Dead Man through to the work 100 years (2016). As the room notes describe it, this is “an epic video installation tracing a century from 1915 to 2015, animating one hundred abstract works. Each work is given approximately one minute to take shape on the screen before it dissipates for the next. Beginning with Malevich’s Black Square, which has repeatedly appeared in Mountford’s films, 100 years gives time to key works in the movement but also to those less known or recognisable. Mountford says, ‘the work draws a line that does not respond to the canon, rather it dips in and out across the century’.”

This is the only work – and it is a major one, projected on a huge scale – that does not include any figures, or figurative content. It spans a century of intense human activity that included two world wars, famines, the rise and fall of empires, the moon landing and the destruction of the Twin Towers. These are all subjects you would think were ripe with possibility for Mountford’s earlier obsessions, not least overt violence mixed with a strong dash of black humour. Yet he covers the century with an endlessly morphing digital tapestry of the most aesthetic, cerebral abstractions.

In his eloquent opening remarks, director of Buxton Contemporary Ryan Johnson, a long-time advocate for Mountford’s work, said “These adventures involve a vast supporting cast including Marcel Duchamp, Jeff Koons, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Patti Smith (among many others), while the scenarios they enact are lifted from, or are inspired by, a diversity of sources ranging from Northern European Renaissance painting to 1980s horror movies. Previously unrelated events collide, and the history of art unfolds again and again in new and surprising ways. These films are always very funny, and almost always just as violent. In Arlo’s practice, everyone – even the viewer – loses their head.”

This last observation brings me to what I think is one of the most successful works in the show – and it is an early work from 2005. It has a simplicity and a circularity that I think the artist should consider returning to occasionally. A series of these works would look fabulous in any international museum. Wedge for S/elective Viewing (2005) mixes video animation with a highly pragmatic constructivist sculpture. It is one of his first animations and is framed by what could be a crazy piece of IKEA furniture. The audience is literally ‘captive’, as the wall text explains: “The viewer is stuck inside the work, their head and body removed from one another, and cannot simply walk away from it.” Inside, the spectators – for this work accommodates two people at a time, standing on wooden platforms – watch a video animation about a decapitation machine being constructed. The idea comes full circle when one realises that this is the very “machine” one is standing inside, and the blades of the guillotines are about to slice backwards through the necks of its conjoined audience. It contains all the laughter and screams of the fairground ghost train, alongside the Tom and Jerry cartoon deaths of our shared childhoods.

2005 was a very good year for Mountford and shows why a mid-career retrospective is so important and appropriate. It is also the year he created Murder in the Museum (2005). Again the catalogue is informative and to the point. “This work is a killer. Taking its cues from Friday the 13th Part 2 in the style of horror films from sleepovers past – Mountford’s protagonists are stalking their victims and mercilessly slaying them one by one, of course in the most iconic museums across the globe, and in front of some of the most recognisable works in art history.” As someone who for the past 25 years has been working on a project called The Art Fair Murders (1994–present) with a similar theme of “serial death in the art world”, I can totally understand where he is coming from. But it is where he is going that leaves me far behind.

Despite the violence, Mountford’s work is nuanced and subtle when he wants it to be. And it can be shockingly beautiful, as in The Folly, a three-screen tribute to Pieter Bruegel the Elder, full of sublime, quiet passages. In front of it, one experiences the stillness of looking at a painting, of entering another world. The left-hand panel appropriates perhaps Bruegel’s most famous work, Hunters in the Snow (1565). I first saw it in Melbourne’s Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP) several years ago, and was immediately transfixed – nay, mesmerised. It has a hypnotic slowness to it. For a long time, it seems as if you are looking at a backlit still image. Then you see a bird, slowly circling in the Northern European winter sky. Eventually – and this is a moment of epiphany – the hunters themselves enter stage left and tramp collegially through the snow, while on another screen, in a different season, the peasants who will later revolt against their overlords dutifully cut and stack corn. A wonderful work, in a beautifully curated exhibition. It makes me wonder, with intense anticipation, “What comes next?” – although there is more than enough work here, appropriating many different styles and media, to keep us anchored to the present and the recent past.

This survey originated at Goulburn Regional Art Gallery and will tour to several venues, but its Shepparton installation is its only Victorian one. The Folly is a very welcome addition to the Shepparton exhibition, and I hope it travels to other venues too; it gives a balance to the survey, like the pole used by a tightrope walker, while all around death and destruction are only a single slip away.

Deep Revolt runs until June 10 at Shepparton Art Museum. The exhibition is developed by Goulburn Regional Art Gallery and toured nationally in partnership with Museums & Galleries of NSW, alongside additional key works by Arlo Mountford.

Arlo Mountford is represented by Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

Image credit: Arlo Mountford, Deep Revolt, installation view.

Shepparton Art Museum, 2019. Image courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery Melbourne.

Photo: Emiliano Fernández

... Subscribe