Reloading the Canon – Why it's time to acknowledge forgotten female artists

In 1971, ArtNews published Linda Nochlin's seminal essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ A clarion call to the establishment then, Nochlin’s essay still resonates in 2019. A rereading of her essay raises the question, who has history still overlooked? Who are the great women artists in history and who deserves to be acknowledged? VAULT asked a series of prominent female curators, artists and creatives to nominate a female artist or artists for whom recognition is overdue.

JOAN GROUNDS

One thing that has stayed with me about Linda Nochlin’s article is the need to be mindful of boosterism: some artists – men and women – have been neglected for good reason. That warning in place, I would pick American-born Australian artist Joan Grounds ( b. 1939) as someone whose work needs to be properly acknowledged by a major show or book. She works in installation, sculpture and performance; most of her work is ephemeral, amplifying its gentle intensity as well as its precarity. Her work is quite simply exquisite; she has the most extraordinary touch with materials. Joan is a serial collaborator so any survey of her work would need to take this into account. Some of my favourite works are collaborations: Familiaceae Obligatum with Sherre DeLys (for Swelter at Palm House, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 1999–2000), UT with Stevie Wishart (AGNSW, 1997), 40 Days and 40 Nights with NS Harsha (AGNSW, 1997).

SUSAN BEST is a professor of art history and fine art at Queensland College of Art, Griffith University. Her current book is titled Impersonality: Self and Other in Body Art and Performance.

Image credit: Ruby Spowart (b.1928), Ground effects - Moreton Island 1988, black and white photographic collage. Collection, Gallery at HOTA. Joint winner, National Women's Art Award Gold Coast Art Prize 1989.

RUBY SPOWART

Ruby Spowart is a Queensland photographer who is well overdue for re-evaluation. Her dynamic work was chosen for one of the two inaugural exhibitions at the Centre Gallery, Gold Coast (now HOTA) in 1986. In 1988, she featured in A Complimentary Caste: A homage to women artists, a major undertaking of women artists in Australia. Her career began when she was in her early 60s. So although her contemporaries were artists such as David Moore, Ruby’s work has a freshness that aligns more with a younger generation of photographers. Her constructed images explore collage and Polaroid techniques and have a clear tendency towards international photography practice in the 1970s. Now in her early 90s (!!), Ruby lives locally and is still active in national photography awards and exhibitions.

TRACY COOPER-LAVERY is Director, Gallery at HOTA, Home of the Arts, and leading the development of Australia's largest regional gallery; the new HOTA Gallery is set to open in 2021.

MIYOKO ITO

Last year (2018), while in New York, a friend recommended I see Heart of Hearts, an exhibition by Miyoko Ito, at Artists Space. So, on the last day of my trip, I caught the subway downtown to Tribeca. Ito’s paintings were magnificent, mostly made in the 1970s in Chicago, when the artist was in her 50s. Her use of colour was impeccable – luminous warm tones, subtle peaches, yellows and golds – often painted in gradation, at once appearing both strong and delicate. The works felt strangely enigmatic and familiar at the same time, and I think it’s this dreamlike quality that has meant I’ve been thinking about them ever since.

GEMMA SMITH is an artist. A survey exhibition, Rhythm Sequence, featuring more than 50 works by Smith, runs until June 1, 2019 at UNSW Galleries, Sydney.

SILVIA INES STANSFIELD and JULIE GOUGH

Through the evocative ceramics of Silvia Ines Stansfield, we are taken on an intimate journey through an extraordinary life. Embedded within her lifelong work are memoirs of her travels, encounters with inspirational people, her love of nature and, most importantly, the optimism and joy she has for life.

Silvia was born in the south of Chile and came to Australia in 1969. Throughout her career Silvia has continually developed her work, exhibiting extensively in solo and group exhibitions in Australia and internationally. She has generously shared her skills and knowledge with other artists, schools and community workshops, including teaching ceramics for 12 years at Tauondi Aboriginal Community College in Port Adelaide. I worked with Silvia at Tauondi from 1996 to 2006. She shared her skills and expertise freely and most generously with the students and has been instrumental in the development of many artists’ careers.

She says about her work: “Clay became a canvas and my hands and mind came together to express my ideas. It is a full life to explore clay and all of its possibilities. I make many objects with different purposes, from the bowl thrown on the wheel to the enjoyment of exploring hand building to develop larger forms – all incorporating personal experiences of landscapes, villages, streets and people.”

Julie Gough is an artist, writer and curator who lives in Hobart, Tasmania. Julie is one of the hardest-working artists I have ever met. Julie’s research and art practice involves uncovering and re-presenting subsumed and often conflicting histories, often referring to her own and her family’s experiences as Tasmanian Aboriginal people. Current work in installation, sound and video provides the means to explore ephemerality, absence and recurrence. With sheer determination she delves into history that is dark, bleak and terribly disturbing; yet through installation, moving image and sound she reinvents it in a way that we as the viewer are able to engage and learn about it.

NICI CUMPSTON is Curator, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia and Artistic Director of TARNANTHI.

BARBARA MCKAY

Barbara McKay graduated from the National Art School in 1960. Her oeuvre is expansive and could represent one of the most enduring and significant abstract expressionist practices in Australia. American art critic Clement Greenberg once singled out a work by McKay from among her fellow Institute of Contemporary Art members – all of whom were male – at his visit to the Central Street Gallery in 1979: an event that initiated a 17-year correspondence and friendship between the artist and critic, who would later write to McKay, “So keep going. You most certainly have it.” McKay would go on to visit Greenberg and to work in New York among contemporaries including Larry Poons and Michael Steiner.

As is often the case for women artists, life, marriage to a successful artist, and motherhood did at times take precedence for McKay. Nonetheless she has consistently exhibited in Australia and overseas and has maintained a relentless belief in, and dedication to, her art practice. In July 2019 McKay will have her first major retrospective at New England Regional Art Museum.

RACHEL PARSONS is Director of New England Regional Art Museum.

NEW WOMAN

Despite the fact there is an increase in female artists’ exhibitions within institutions and a growing prominence [of women’s art] in international forums, today gender remains a critical global factor when assigning value to art. As a Director of a City Museum, my vision is to invest in sustainable practice and raise the profile of local artists through commissions, acquisitions and a diverse program. In September, Museum of Brisbane will launch New Woman, an exhibition that explores the enduring legacies of 70 of Brisbane’s significant and groundbreaking female artists over the past 100 years. The idea for this exhibition was inspired by leading 1920s artists and advocates Daphne Mayo and Vida Lahey, who set the scene for the vital role women played in gaining respect and investment for the city’s arts. Acknowledging the contribution of those who have come before us, New Woman signifies the vast changes in ideas of gender, artistic styles, subject matter and ways of seeing the world.

RENAI GRACE is Director, Museum of Brisbane

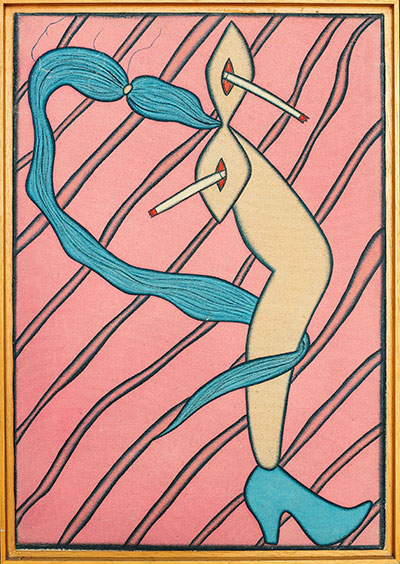

Image credit: Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih Berpesta di Bangkok (Party in Bangkok) 2003, Chinese ink and synthetic polymer paint on canvas, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Purchased 2019

MURNI

With an unswerving vision, I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih (1966–2006), known as Murni, painted compositions of contorted body parts, and bizarre creatures engaging in taboo subject matter and enacting vivid fantasies. Equally grotesque, explicitly sexual and humorous, Murni’s works celebrate the power of female-led eroticism as a feminist framework and tactical guide for herself, and others, in combating gendered oppression in everyday life. Symbolic forms were used as transgressive tools against the Indonesian government’s promotion of the Panca Dharma Wanita (Five Duties of Women), thus exposing normative roles as products of systemic conditioning. More widely, Murni worked for equality on creative, psychological and physical terms, trailblazing a new painting style that radically altered the male-dominated genre of Balinese Pengosekan painting. As part of an organised response to the contemporary reverberations of Linda Nochlin’s call for institutional and educational change, the NGA has acquired several of Murni’s paintings for the national collection, with a forthcoming exhibition of her work in Contemporary worlds: Indonesia set to open on June 21, 2019.

JAKLYN BABINGTON is the Senior Curator, Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

ALICE NEEL

I first came across Alice Neel when I was at art school in the ’90s and I was struck by the honesty and empathy in her work. Her portraits depict the gamut of human vulnerabilities, emotions and attitudes. When figurative painting was unfashionable she was someone I deeply admired for her unshakeable vision. Nochlin called her work “portraits of a universal existential anxiety” and they resonate through time and are more relevant than ever.

FIONA LOWRY is an artist.

Image credit: Bonita Ely, Murray River Punch, 1980, performance documentation, 15:38 duration

BONITA ELY

Bonita Ely is an artist whose work is so pertinent it deserves a major reconsideration. Since the late ’70s, she has been making work about the Murray River and the impact of human exploitation on its fragile ecology. Her performance Murray River Punch with its deadpan delivery could not articulate more clearly the problems that have hit the headlines again in the past few months. In her work, which focuses on oral history and storytelling, she brings together Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives. She was included in the last Documenta, arguably the most important global exhibition that takes place in Germany every five years. For this exhibition, Ely expanded the theme of trauma resulting from environmental damage to that caused by the horrors of war and its impact on displaced peoples. Her work demonstrates how artists can powerfully articulate the key issues of our times.

ELIZABETH ANN MACGREGOR OBE is Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

LUCIA MOHOLY

As we celebrate in 2019 the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus, it would make sense to look at female artists who were part of the famous German art school in the 1920s and who experimented art in an innovative way. Lucia Moholy (1894–1989) or Anni Albers (1899–1994) were both artists who played an active part in 20th-century modernism yet who have long been overshadowed by their husbands: artists and theoreticians Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers, both considered as forerunners of modern art. However, few people recognise the importance of their wives. It was not until 2018 that a major retrospective dedicated to Anni Albers took place at the Tate Modern in London. Lucia Moholy hasn’t reached this recognition yet. Married to famous artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in 1921, Lucia Moholy explored photography from the first day the couple arrived at the Bauhaus, and initiated her husband into photography. We know from her that the first photograms were made together. Lucia Moholy’s photographs played an important part in the way the school advertised photography, and built its identity. However her experimentations in the darkroom and with the camera were not recognised, and the history of photography has only remembered her husband’s name, despite the fact that in 1972 Lucia Moholy wrote a book (Marginalien zu Moholy-Nagy), to reclaim her own work. It is necessary today to study more carefully the contribution of this artist to 20th-century photography.

NATHALIE HERSCHDORFER is a curator and art historian specialising in the history of photography, and Director of the Museum of Fine Arts Le Locle, Switzerland. She has been working as a curator with FEP (Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography) for several years.

Image credit: Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Iran b.1924, Lightning for Neda (detail), 2009, mirror mosaic, reverse glass paiting, plaster on wood / six panels: 300 x 200 x 25cm (each); 300 x 1200 x 25cm (overall).Purchased 2009 by the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery. Image courtesy the artist

MONIR SHAHROUDY FARMANFA

My nomination goes to an artist whose work I, happily, first discovered here in Brisbane while walking the rooms of the Gallery of Modern Art. I still remember the first time I gazed upon the deftly articulated reflective surfaces of her work Lightning for Neda (2009): a spectacle of light and impossibly intricate geometry; a contemporary mosaic of mirror, reverse glass, paint, plaster and wood. Persian artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian created this exceptional work. Layered with cultural references and political nuance, Farmanfarmaian’s work explores the nexus between traditional Iranian architectural decoration – specifically the technique known as aineh-kari, an artform dating back to the 16th century – and the Western philosophies of minimalism and abstraction. After creating for over 75 years, Farmanfarmaian is still very much a practitioner at the ripe age of 96. Except for her appointment to exhibit within the Iranian Pavilion at the 1958 Venice Biennale, awards and accolades have been few; it is only recently and very late in her long and active career that she has been internationally noticed. In 2011 Hans Ulrich Obrist authored the eponymous book, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Cosmic Geometry. In 2014 the first museum retrospective of her work was curated by Suzanne Cotter at the Serralves Museum in Porto, Portugal before touring to the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York (2015). Most recently, in 2017 the Monir Museum in Tehran, Iran was opened in her honour. Of the Portugal and New York exhibitions, Farmanfarmaian said, in a 2015 interview with Artforum International, “These recent shows have been a remarkable time in my life because for so long I was really a nobody. Little by little, I’ve become… I don’t know… better known? Certainly, the Guggenheim wasn’t giving me a show until now.” [Editor’s note: Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian died on April 20, 2019.]

NATASHA SMITH is Principal Curatorial Leader with Urban Art Projects (UAP).

THE BEST IS YET TO COME

The best is yet to come. Though there have been countless injustices in regard to the recognition of female artists and designers throughout history, it is rewarding to see how these wrongs are being redressed to create a different future. It’s particularly inspiring to see women artists in their 80s, 90s and 100s finally being given the recognition they deserved. It resonates with the ‘Nevertheless, she persisted’ movement. Artists such as Yayoi Kusama, Carmen Herrera, Hilma af Klint and Beverley Pepper have endured injustice but have stayed committed and true to their vision. Many of these artists are now able to witness a victory of due acknowledgement and celebration of their achievements in their lifetime. They stayed true to themselves and worked their entire lives on their true, authentic creative course. Sites such as @repaint.history on Instagram are also bringing awareness and recognition to forgotten female artists.

LIANE ROSSLER is an artist, designer, curator and creative advisor who has spent the last decade focused on projects that intersect art, design and the environment. Alongside her solo creative practice, she is founder of Superlocalstudio, which inspires collaborative, socially engaged cultural and creative projects for diverse audiences.

SIMONE WEIL

Simone Weil existed always on the threshold of the church – she was never baptised; she was not a Christian. In 1928, French philosopher Simone Weil (1909–1943) came first and Simone de Beauvoir second in their entrance examinations at the competitive École Normale Supérieure, Paris, both topping a class of 30 men. Attente de Dieu / Waiting on God is a collection of essays published posthumously in 1950. It comprises Weil’s most profound meditations on the relationship of human life to the realm of the transcendent, a spiritual autobiography (a self-portrait) couched in non-ecclesiastical form and in biting expression. I have read it many times, with my heart first and my intellect second. It holds some of the most profound allegorical statements on the practice of art that I have come across. Weil’s philosophy of prayer might stand for art.

Weil’s concept of attention is the thread that links the act of prayer and the act of creating and experiencing art. Though her writing on attention is linked to Christianity through the powerful analogy of attention in prayer – a metaphysical movement of the soul in the direction of God – attention is, first, a fundamental part of the physical and mental structure of man.

Weil’s work dissolves the gulf between the physical and abstract world. Within her thought that which is worldly, base and human connects with the abstract and unseen in a concrete way. It is through attention that the most abstract of spaces can be transformed into penetrable, tangible form. In light of this narrowing and illuminating effect, it is possible, through attention, to bring into the physical world manifestations of experience that are vastly abstract. This notion of collapsing conceptual and corporeal realities translates fluently to the construction of art, where we seek to diminish the space between concept and representation.

DR LISA COOPER is an artist and florist.

ANNE WALLACE

One need only explain the eerie image of Anne Wallace’s 1996 painting Damage, held in the Queensland Art Gallery collection, with a few succinct words to conjure the image in one’s mind: Lynchian scene, dripping blood, alabaster flesh. Wallace painted the work aged 26, and it is no overstatement to ascribe a prodigious ability to her highly accomplished figurative paintings. Wallace has an uncanny ability to tap into a shared psyche, with the interplay of meaning and associations that draw upon the language of pop culture; and like any good ‘story’, there is sexual and social confusion, vulnerability and violence, alienation and loneliness, feelings of the abject, or fantasies of power and revenge. She has maintained a consistent and highly recognised style for over three decades – through times when the figurative genre was considered hidebound. Surprisingly, despite seeing an increasing interest in this genre, there have been no major institutional survey shows of Wallace.

Image credit: Anne Wallace, Damage, 1996, oil on canvas, 134 x 165 cm

VANESSA VAN OOYEN is Senior Curator of the QUT Art Museum and William Robinson Gallery.

eX DE MEDICI

eX de Medici has been at the battlelines of political art in Australia since the 1980s. From the 1990s, she has worked almost exclusively in the genteel and unforgiving medium of watercolour – making exquisitely beautiful, forceful and often enormous statements (some of her watercolours measure over seven metres) about power and politics. They lure you in with their seductive detail, then smack you in the face – to quote Doug Hall, hers is “an iron fist in a velvet glove”. While de Medici’s work has been collected by almost every state institution, and a large overview of her work is held at the NGA – de Medici is one of Canberra’s own – she is yet to receive a survey at a state institution. Her solo at the ACT’s Drill Hall Gallery drew record crowds and was testament to the impact that this artist has had on generations of artists, especially in the ACT. She is one of the most intelligent and insightful commentators of our times, and now more than ever, this work needs to be seen.

JOANNA STRUMPF is co-director of Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney+ Singapore, a contemporary gallery which she founded with Ursula Sullivan in 2005.

BONITA ELY

Bonita Ely (b. 1946, works in Sydney) has been active since the early 1970s with an interdisciplinary practice that includes performance, photography, video and sculpture. Her work has been seen extensively internationally, most recently in documenta14. In Kassel, Interior Decoration (2013–) explored the intergenerational consequences of post-traumatic stress disorder as an outcome of war, with an uncanny domestic space constructed from her parents’ bedroom furniture. In Athens, Plastikus Progressus: Memento Mori (2017) imagined a dystopian futuristic museum display documenting new taxonomies of genetically engineered, plastic-eating flora and fauna. The warning of impending environmental crisis in Ely’s 1970s works is now remarkably prescient. She remains absolutely committed, recently climbing into polluted waters at Menindee to be photographed surrounded by dead fish. The resulting image is redolent of John Everett Millais’s painting of drowning Ophelia (1851–2), currently on display at the NGA! Yet, she’s not had a major art museum survey in Australia or a monograph publication.

ANGELA GODDARD is Director, Griffith University Art Museum, and a board member of Sheila: A Foundation for Women in Visual Art.

JENNIFER HERD

In the last few years, Jennifer Herd has created strikingly beautiful and yet horrifying works from large sheets of white Aquarelle Arches paper, each carefully changed by thousands of pinpricks. The perforations depict Aboriginal shield designs from North Queensland, and in the accumulation of small gestures – each one an act of violence – Herd allows us to consider the truth of Australia’s frontier wars, where warrior shields could not withstand bullets. Herd has family ties to the Mbar-barrum people. She is a founding member of the artist collective ProppaNOW, and she taught at the Queensland College of Art in Brisbane from 1993 until she retired in 2014 from her role as Convenor of Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art. Since moving to Brisbane, I have met so many artists and art workers whose eyes invariably light up when they speak of her deep influence in their lives, and I know of her impact during periods in which we worked together. I am so pleased that Griffith University Art Museum has acquired four works, titled Diamond series II (2016), and I would so like to see the breadth of her practice brought together for a major survey, charting her work in the fields of dramatic arts and costume through to her vocation as an artist and her position as an extraordinarily well respected senior leader and thinker.

NAOMI EVANS is Curator, Griffith University Art Museum.

... Subscribe