Nicole Eisenman: Myths and Misconceptions

Artist Nicole Eisenman makes contemporary history paintings for now.

Image credit: Nicole Eisenman, Dark Light, 2017, oil on canvas, 323 x 266.7 x 4.4 cm. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer. Courtesy the artist and Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Nicole Eisenman made some major strides in their career in 2019, creating significant new work for inclusion in two of the art world’s most eagerly anticipated exhibitions: the 58th Venice Biennale, entitled May You Live In Interesting Times, curated by Ralph Rugoff (director of the Hayward Gallery in London), and the 2019 Whitney Biennial, in its 79th iteration, curated by Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley.

VAULT Editor Alison Kubler chatted to Nicole Eisenman and unpacked the layers of their career and work in the midst of this remarkable year for the artist.

Where the Venice Biennale casts its eye across the diaspora in an attempt to present a global perspective on the times in which we live, the Whitney Biennial takes the temperature of America quite specifically.

At the time of writing, Eisenman’s contribution to Venice is unclear; for the Whitney they are working on a large-scale multifigure sculptural installation – a tableau of monumental figures – for the museum’s sixth-floor terrace. It’s fair to say Eisenman’s dance card is full.

Significantly, this will be the artist’s second inclusion in the Whitney Biennial; their first inclusion was in 1995 and that exhibition proved something of a catalyst for their significant career to follow. Eisenman has been at the forefront of contemporary art practice in America since the 1990s, and their inclusion in two such seminal concurrent surveys some 30 years later is evidence of their work’s enduring quality. In 2016 they were the subject of a major survey at the New Museum, New York, entitled Al-ugh-ories; in 2015 they were awarded a MacArthur Fellowship; and more recently they were selected as the winner of the 2020 Suzanne Deal Booth/FLAG Art Foundation Prize, worth US$200,000. Eisenman is arguably one of the most significant painters of their generation. They may in fact be the painter.

And this is important because their work seems to argue a case for the longevity of painting, as well as figuration – not to mention history and allegorical painting.

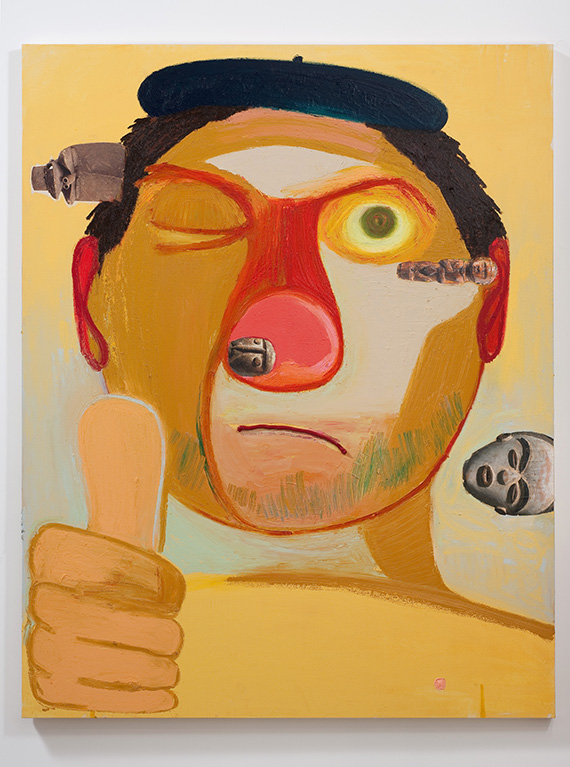

Their considerable oeuvre might be seen as a love letter to the history of art, imbued as it is with references to painters and movements, and yet it remains implacably contemporary. They have developed a style and a language that is almost unmistakably their own. Eisenman’s work eschews realism for atmosphere; their works pays homage, perhaps, to painters such as Philip Guston or George Condo by adopting those artists’ exaggerated human forms, bulbous bodies and cartoonesque features; but then at times, they veer back to classicism with paintings that are decidedly delicate and fine in their rendering by comparison. Eisenman’s paintings are variously grotesque and humorous; they are not a polite painter. Their palette, too, is a riot of nonsensical tones, by turns childlike and garish.

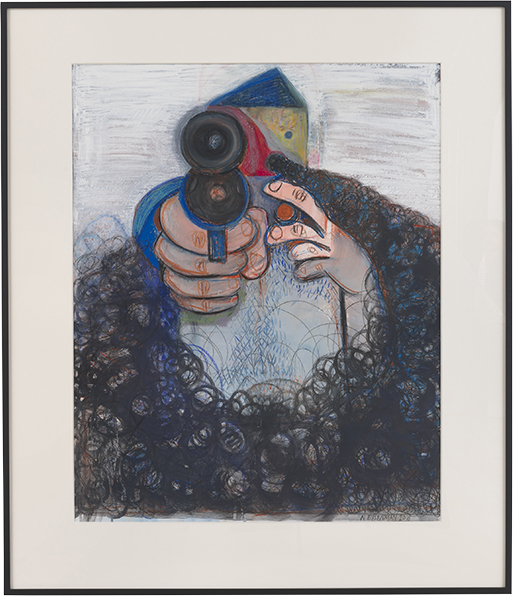

In terms of subject matter, they do not distinguish between the private and the public. Much of their work can be read as autobiographical: mundane, even, in its domestic detail of the artist’s everyday life; but the subject matter is also often political in tone. Their paintings describe their queerness but refuse any kind of virtue signalling but chooses to subvert gender norms. When they tackle history painting, yes, there is the obvious implication that they are subverting a masculine history painting tradition, but their work’s strength comes from its unwillingness to be overly didactic. Eisenman assumes their audience is up to speed. Perhaps the most overt they get is with a series collectively entitled Shooter, variously depicted in ink, charcoal, oil, acrylic and pencil. For an audience outside of America they read as a comment on a nation irrevocably wed to violence, at the whim of a powerful gun lobby. The Shooter (2018), for example, casts the viewer as victim but also as complacent observer, as though Eisenman is suggesting, you can’t have it both ways.

Dark Light (2017) offers an ode to religious allegorical painting, a favourite genre of the artist. It depicts four men in the bed of a ute – or as Americans might say, a pickup. One figure stands upright shining a torch into the gloom; he wears a red cap suggestive of Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ merchandise – although Eisenman stops short of painting the logo – and camouflage gear. Behind the characters a giant orifice spews oil out, a reference to the American practice of “rolling coal”, in which the engine of a diesel vehicle such as a pickup truck is modified to allow more fuel to be injected into the engine by the driver, in order to release a cloud of toxic exhaust. It is a strategy used to harass cyclists and has been used to disrupt environmental demonstrations by right-wing opposition, too. Against this background the scene takes on a menacing air; something sinister is afoot, or is it? Is the painting a contemporary parable, an ironic reappropriation of William Holman Hunt’s Pre-Raphaelite painting The Light of the World (1851–53)? Is the man in the red cap illuminating the darkness for the ignorant left who have rejected Trump? MAGA hats always remind me of the bonnets rouges worn by the French revolutionaries; they are worn with the same righteous belief in the disruption of the status quo and the rise of the working class; and yet they have come to symbolise right-wing ignorance and white privilege. Although the spectre of Donald Trump looms large, the artist has stopped short of painting him, although they have drawn him many times in other works. It is as though they deem the subject unworthy of the gravitas of painting.

Dark Light featured in the exhibition of the same title at the Vienna Secession, Austria in 2017 alongside another grand allegorical work, Going Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass (2017). Stylistically it is a very different painting, rendered in finer, flatter detail. The work depicts a man playing a flute, accompanied by a sailor and businessman, sailing in a boat made of a jawbone on a pea-green poisonous river towards a perilous waterfall. The protagonists are seemingly unaware of their imminent doom – fiddling while Rome burns.

Recently Eisenman has been gaining recognition for their sculptural work, to which they returned in 2013. In 2018 they staged their first solo exhibition in Germany at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, with a focus primarily on sculpture. Their works in the sculptural realm move across materials and dimensions, from bronze and aluminium with paint to plaster, a favoured material. Their sculptures are a brilliant departure from their paintings: awkwardly physical, they describe their very own making in the chunkiness of the material and largely reject the weightiness and permanence of traditional sculpture.

For the 2017 Skulptur Projekte Münster, Eisenman made Sketch for a Fountain,

a tableau of figures around a pool of water. Two of the five figures are rendered in bronze; one stands inside the pool, water cascading from various body parts, a human fountain, and the other reclines. Another three figures, genderless and larger than life, recline around the pond, cast in plaster. Subject to the elements, they offered a meditation on permanence and impermanence. Their precarious nature meant, too, that one of the works was decapitated, its head souvenired. Another work was defaced with a swastika. The artist declined to repair the work: a gesture that speaks to their preparedness to let the work be a vehicle for difficult conversations. This recent foray into sculpture further cements their place in contemporary culture.

Nicole Eisenman, Giant Without a Body is currently showing at Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, until August 29, 2021.

Nicole Eisenman is represented by Suzanne Vielmetter Projects, Los Angeles, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth.

afmuseet.no

vielmetter.com

antonkerngallery.com

hauserwirth.com

Image credit: Nicole Eisenman, Guy Artist, 2011, oil and collage on canvas, 193 x 152 cm. Courtesy the artist and Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Image credit: Nicole Eisenman, Sketch for a Fountain, 2017. © Skulptur Projekte. Photo: Henning Rogge

Image credit: Nicole Eisenman, The Shooter, 2018, ink, charcoal, oil, acrylic and pencil on gessoed paper, 129.5 x 111x 5 cm. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer. Courtesy the artist and Vielmetter, Los Angeles

This article was originally published in VAULT Issue 26, MAY 2019.

Click here to Subscribe