JAPAN SUPERNATURAL: Takashi Murakami and his scary monsters

A new major exhibition at Art Gallery of

New South Wales traces Japan’s fascination with

the Otherworld from the Edo period until now.

Portrait of Takashi Murakami

Features artwork at rear:

Takashi Murakami

Tan Tan Bo Black Hole, 2019

acrylic, Gold and platinum leaf on canvas mounted on aluminium frame

240 x 735 cm

Headpiece and Foot Casting: Amazing Studio JUR (Part of the costume for the 2014 Exhibition Opening at Gagosian New York)

Photo: Takuo Arai

Many of the most-loved children's fairytales across history are remarkably macabre stories, peopled by child-eating witches, evil queens, dragons and ghosts. Think of the Grimm Brothers stories, for example, or even Hans Christian Andersen's fables. Almost every culture has a version of these portentous tales but perhaps none are quite so compelling as those that have stemmed from Japanese culture.

Japan Supernatural, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales as part of Sydney International Art Series, features over 180 works by some of the greatest Japanese artists over the last 300 years and examines the rich tradition of the supernatural in art from the early Edo period through to now. The Art Gallery of New South Wales Senior Curator of Asian Art, Melanie Eastburn explains, �Japanese artists have used intricate narratives and powerful imagery to make the invisible world of the supernatural tangible.� The origin of the exhibition lies partly in Eastburn's childhood fascination with a book she had as a child called The Badger Woods (1977) by Iraphne Childs, a collection of Japanese folktales.

Known in Japan as yōkai, yūrei, bakemono and mononoke (expressed in artwork as animals, fiendish imps, monsters and ethereal spirits), evocations of the paranormal are everywhere in ancient Japanese folklore, but are still hugely popular today. Yokai often have animal traits and can shapeshift, as can bakemono; yurei are ghosts who left their human souls in tragic circumstances, by murder or suicide, and who exist in an in-between state, most often returning to their past lives. Mononoke are particularly evil spirits.

Popular horror film franchises such as The Ring emerge from these tales told for hundreds of years. The Hollywood version is based on the 1998 Japanese original Ring, which in turn is based on the 1991 novel of the same name by witer Koji Suzuki. Eastburn also points to the popularity of Pok�mon, with its ubiquitous trading cards. In Japan they are known as �Pocket Monsters.' Eastburn explains, �Each creature has unique traits and abilities, much like the characters in Japanese tales. They never were exactly the same characters but, say, when Toriyama Sekien made his 1770s compendium of monsters with drawings and descriptions of them, and included information on how big they were and what they liked to eat, et cetera, it is very much the basis of Pok�mon.� The exhibition provides an rigorous examination of the supernatural and a treasure trove of the weird and the wonderful. There are rare woodblocks and seminal artworks borrowed from collections all over the world, including the Broad Art Museum, the British Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Minneapolis Institute of Art. A key work is Toriyama Sekien's five-metre-long scroll, Night Procession of the Hundred Demons (Hyakki yakō zu, c1776), which depicts a parade of spooky characters. Borrowed from the MFA, Boston, it is something of a coup for Sydney. There is also Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's series One hundred ghost stories from Japan and China (Wakan hyaku monogatari, 1865) as well as Momotarō scattering beans for setsubun (Momotarō mamemaki no zu, 1859).

The exhibition brings together large-scale installations, miniature carvings, illustrations and ukiyo-e woodblock prints with work by the late manga artist Mizuki Shigeru and contemporary artist Tarō Yamamoto alongside important works by leading female Japanese contemporary artists Fuyuko Matsui, Miwa Yanagi, Tabaimo and Chiho Aoshima. From the British Museum is the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Mitsukuni defies the skeleton spectre conjured up by Princess Takiyasha (1845�46), a woodblock print triptych, which depicts one of Japan's best-loved horror stories, in which a terrifying giant skeleton, or ōdokuro, is summoned by a princess in revenge for the murder of her father. It is ghoulishly beautiful; despite their age the woodblocks and scrolls are richly vibrant, with all the immediacy of the era in which they were produced to be made apparent. They are the key to understanding so much of contemporary manga, animation and contemporary pop culture at large.

Significantly, the exhibition's centrepiece is a monumental installation of painting and sculpture by one of contemporary art's biggest stars, Takashi Murakami. In Japan Supernatural Murakami's work offers an entry point for a contemporary audience to the rich cultural tradition. Murakami explained to VAULT why he returns to these enduring Gothic tales in his work: �Monsters symbolize fear. Kaijū like Godzilla became as popular a symbol of fear as did religious demons and depictions of Satan. They come out of the experience of having tens of thousands of people blown up and vanish due to the two atomic bombs during the Pacific War. I am also depicting samurai warriors, who long existed in the environment where they could carry swords and chop people up. Instilled in their swords are both the fear of killing people and the envy for power. I feel that yōkai are the embodiments of such fundamental desires of people.�

Eastburn explains, �For Murakami, there's his interest in the works of the Edo period; these are quite direct connections. And then taking those characters like the Oni from children's stories [oni are a kind of yōkai best described as an ogre or troll] and making them giant.� Murakami has two enormous sculptures in Japan Supernatural, these include Embodiment of A and Embodiment of Um, both from 2014, which relate to the Oni. She adds, �Murakami is looking both at the modern Japan Edo period, but also at manga and anime from the 1960s. His connections are quite circuitous; they're sort of complicated because they're an individual's experience.�

The exhibition also looks at the legacy of Japanese animation house Studio Ghibli. In 2013, Murakami premiered Jellyfish Eyes, the story of a lonely child who stumbles upon a strange jellyfish-like creature called F.R.I.E.N.D. VAULT asked him if he had considered making a film in the same vein. �Right now I'm making an animation work. It is basically a nightmare: it is a financial drain and I can't control people involved. I just completed the seventh episode of my TV animation series and we have the completion party after it airs, but I can't simply celebrate because the production has been costing me so much.�

Murakami and the American artist KAWS � who is featured in this issue too � are mutual fans and regularly appear on one another's Instagram; like KAWS, Murakami is something of an enigma. He has had a long association with Australia, exhibiting as part of the original 1996 Asia Pacific Triennial at Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art with an early version of his now iconic �Mr DOB' character, And then, and then and then and then and then (1994). Since then Murakami has had, like KAWS, an impressive career � he is a Japanese artist with a truly global profile. This is in part due to his hugely successful collaboration with French luxury house Louis Vuitton, which began in 2004 under the creative directorship of Marc Jacobs, who invited the artist to reinvent the company's famed logo.

Louis Vuitton has collaborated with many artists, but none has been as fruitful or commercially successful as the Murakami project, which revolutionised the coalescing of art and fashion, and sparked a global phenomenon. He developed in-store sculptures and installations to house the products that Jacobs himself described as a �monumental marriage of art and commerce.� Murakami later reappropriated his work with Louis Vuitton, incorporating the paintings and sculptures he produced for the house into his solo practice.

Murakami cuts across culture, melding high and low, fashion and art. One of the biggest music artist today, Billie Eilish � who regularly wears Louis Vuitton � has also in turn collaborated with Murakami, he explains how the pairing came about. �I saw Billie's picture wearing a great outfit on Instagram, so I wrote �Cool' in the comment and our communication started. She subsequently came to Japan for a music festival and our various projects started.� Murakami made an animated video for Eilish for her darkly feminist anthem, �You Should See Me in a Crown', that was accompanied by a limited-edition doll of Eilish. It is super kawaii and super creepy. It is also reminiscent of any number of yūrei in the exhibition. Eilish and Murakami also collaborated on a range of clothing, which has unsurprisingly sold out.

Japan Supernatural runs at Art Gallery

of New South Wales until March 8, 2020.

Takashi Murakami is represented by Galerie Perrotin.

His solo exhibition Baka is at Galerie Perrotin, Paris until December 21.

artgallery.nsw.gov.au

perrotin.com

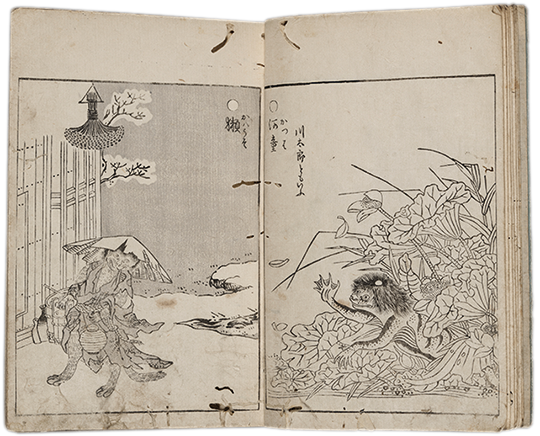

Katsushika HOKUSAI

The ghost of Kohada Koheiji, from the series One hundred ghost stories (Hyaku monogatari)

woodblock print; ink and colour on paper

26.3 x 18.5 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art, gift of Louis W Hill, Jr

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art

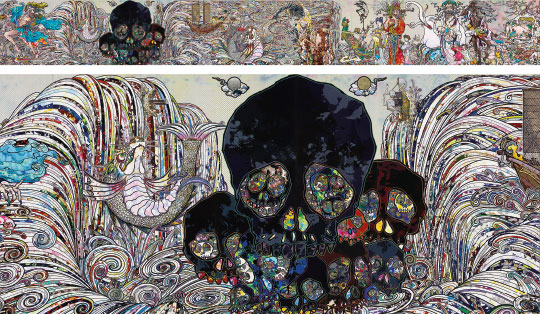

Takashi Murakami

Embodiment of �Um�, 2014

Photo: Joshua White

Takashi MURAKAMI

In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow, 2014

acrylic on canvas mounted on wood panel

300 x 2500 cm

The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles

Photos: Kaikai Kiki

Night procession of the hundred demons, 1776

illustrated (Gazu hyakki yagyo-) woodblock-printed book

22.4 x 15.7 cm (overall)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs Jared K Morse in memory of Charles J Morse

Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

... Subscribe