Amos Gebhardt:

Of Care and Kin

Amos Gebhardt’s poetic and profound video works are a love letter to the power of interdependence – while making space for multiple ways of being in the world.

Image credit: Amos Gebhardt, Evanescence (Salt # 3), 2018, archival inkjet pigment print. Courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Amos Gebhardt has been entranced by images for as long as they can recall. When the artist and filmmaker was a child, they were hungry for visual culture. They pored over photographs in magazines. They stayed up late watching cinema. They also noticed that certain pictures could leave an imprint on the body, charged by a strange and mysterious power.

“I always grappled with what made a particular image reach into my senses – what was it about the way light fell on a face, the way a composition was angled, that could grip me more?” says Gebhardt over Zoom. “It wasn’t until I began formal training that I started to really understand the myriad choices available to impact the emotional experience of viewing something.” They flash a megawatt smile. “[Then] there’s the remarkable miracle of putting one image in between two others and changing its context.”

In October 2020, Gebhardt, who is based between Melbourne and regional South Australia, showed a three-channel video installation called Small acts of resistance (2020) at the Samstag Museum of Art in Adelaide. The work is a lesson in resonance and congruence. A picture, as the saying goes, speaks a thousand words. But here, where images appear side by side, they multiply singular visions, exposing invisible threads that stitch disparate scenes together.

A highway bridges a river, dense with foliage. It’s flanked by armies of red crabs that scuttle across a forest floor, part of an annual migration that sees millions of crustaceans travel to the coast to breed on Christmas Island. Aerial views of the desert, surface pockmarked like skin, give way to a shot of Eric Avery, a Ngiyampaa, Yuin, Bandjalang and Gumbangirr violinist, returning to his ancestral Country. He sings in his father’s tongue and levitates into the sky. On either side of him, bats soar over a Melbourne dusk. The borders between nature and city dissolve, and humans and animals embark on parallel journeys: migrations, homecomings, becomings.

Enlightenment thinking separates people from places, creates divisions between species, traffics in fixed categories. So how do you find a visual language that speaks to the power of interdependence, to the web of connections that holds our world?

“We are at a very precarious time globally and it is high time we call into question power structures that aren’t serving all of us,” Gebhardt says. “The amount of biodiversity lost in the last 200 years correlates with colonial conquests of people and places. I’m interested in being able to articulate these efforts to survive and resist and coexist.”

Gebhardt studied law and screen production at Flinders University, and completed a Master of Directing at the Australian Film Television and Radio School. As a child, Gebhardt couldn’t see themselves in conventional cinema. “[It] has a very narrow representation of humanness,” says Gebhardt, who was drawn to the work of filmmakers like Chantal Akerman, Abbas Kiarostami and Carlos Reygadas. “I honed my career, in

a way, to form a critical resistance to some of the homogenisation that saturated my viewing experience as a kid.”

After graduating, the artist embarked on a successful trajectory as a writer and director. In 2007, Look Sharp, Gebhardt’s moody short film that revolved around the sharpie gangs of 1970s Melbourne and took cues from the work of Nan Goldin and Carol Jerrems, was part of the Saatchi & Saatchi New Directors Showcase. Then, they wrote and directed the ABC documentaries Heart (2008) and Carnival Queen (2011), and worked on critically acclaimed films such as Snowtown (2011) and Macbeth (2015). But they also became increasingly aware of filmmaking’s limits.

In 2014, Gebhardt won a Sidney Myer Creative Fellowship.

“I was asked to make work for a concert for Kate Miller-Heidke with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra, and showed video works at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) as an adjunct to that,” they recall. “I could experiment with my articulation of subjecthood and [ask]: ‘how can I create an energy that goes beyond plot lines and beneath the surface of things?’ For me, it was about having the courage to leave the safety of a script.”

Scripts shape the stories we tell ourselves – but they can also tether us. There Are No Others, a 2016 video work that debuted at MONA and showed, soon after, at Melbourne’s Gertrude Contemporary, depicts naked gender diverse bodies ascending and descending among the clouds, limbs outstretched as if reaching towards freedom. The figures are buoyed by chords that rise and swell, composed by multi-instrumentalist Oren Ambarchi. The nude, of course, has a fraught role in Western art, the object of gendered assumptions about power, sex and desire.

There Are No Others unburdens the nude from the weight of this history.

“I’m interested in the naked body as this incredible archive of our personal stories,” Gebhardt says. “It has etched onto it our scars and sites of trauma and aspects of shame, as well as a vast ability to sense

and express.”

But There Are No Others is also interested in liberating the body from religion and patriarchy, recasting it as a portal to the sublime. “I wanted to allow these figures who are refusing dominant gender norms to have a heroic quality to them,” they muse. “They are carving out non-conforming pathways even though this can be injurious and take a lot of labour. That is a transformative act.”

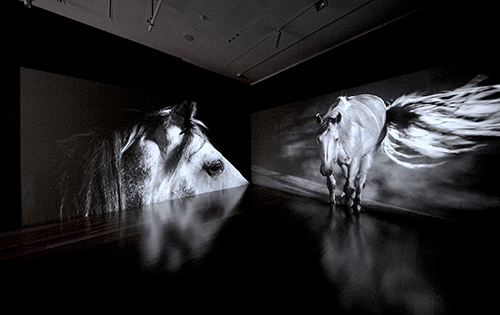

In Evanescence (2018), a four-channel video installation that showed at the

2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art,

40 naked bodies – spanning different shapes, ages and cultural backgrounds – move in endless cycles amid landscapes that range from Boorong Country in Victoria to Barkindji, Mutthi Mutthi

and Ngyiampaa Country in south-west New South Wales. In the work, a collaboration with choreographer Melanie Lane, the figures dance in unison. The geological formations – an ancient rockface, a waterfall, the desert – feel alive, imposing. Like bodies, they are the keepers of unsaid histories.

“I’m interested in the way landscapes, like the body, hold histories and phenomena of and beyond the human register,” Gebhardt explains. “I wanted to cast people who reflect the many personal histories of arrival in this place – from diaspora and the seeking of asylum to colonial invasion. And yet this remains contested land, Aboriginal sovereignty was never ceded. With all its complexities and injustices, we collectively hold the story of being here.” They pause. “There are moments of accord with the landscape and each other. But there are these moments of rupture, where there is violence and brutality as well.”

In Small acts of resistance, the red crabs march across rocks and roads and highways, the fact of their spectacle securing temporary protection from humans. Beyond the frame, Australia detains refugees at the Christmas Island Detention Centre. Near the beginning of the work, queer Fijian-Indian performance artist Raina Petersen dances in front of a squat bungalow, typical of Australian suburbia. Their dance is interspersed with shots of family artefacts – a bowl of rice, a kangaroo-shaped toothpick holder. Assimilation and erasure are forms of violence that are ongoing, but their body is a dissenting force.

For Gebhardt, however, dissent is only one part of resistance. The work also features five members from House of Slé, a ballroom collective and vogueing community comprising queer and trans people of colour in Western Sydney. Bhenji, Jamaica, Taimania, Kilia and Eliam appear underwater, held by elemental forces that shimmer around them. Two fathers, Kelly Lovemonster and Spencer Dezart-Smith, huddle together over their baby, surrounded by diverse members of their chosen family. They appear in triptych, framed by the lush tropical jungle.

But this picture of devotion and care is free from religious duality. Here, love isn’t confined to blood kin. It extends beyond the human body, part of the fragile web of connections that hold our world together.

“It’s important to me that ideas of love and kinship are celebrated, so that they can form powerful counter-narratives,”

Gebhardt says. “Sometimes resistance can

be really small and deeply personal – but

it matters.”

Amos Gebhardt, Spooky Action (At a Distance) shows at The SUBSTATION, Melbourne from February 11 to March 27, 2021 as part of PHOTO 2021.

Amos Gebhardt is represented by Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne.

Image credit: Amos Gebhardt, Family Portrait, 2020, archival inkjet pigment print, 119 x 174 x 6 cm (framed). Edition of 6 + 2 APs. Bowness Photography Prize 2020 finalist. Courtesy the artist

Image credit: Installation view Amos Gebhardt, Lovers, 2018 at Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Divided Worlds, 2018 Samstag Museum of Art, University of South Australia, Adelaide. Photo: Saul Steed

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 33 (Feb – April 2021). Click here to Subscribe