On being alone, not Lonely: The Solitude of Roni Horn

Roni Horn is one of the most interesting artists working today. Her career spans a multitude of forms and media, often exploring the connections between language and imagery, nature and humanity. Horn has an intimate connection to Iceland, which she has visited and made artwork about since the 1970s. Her latest book, Island Zombie: Iceland Writings, is a mediation on that place.

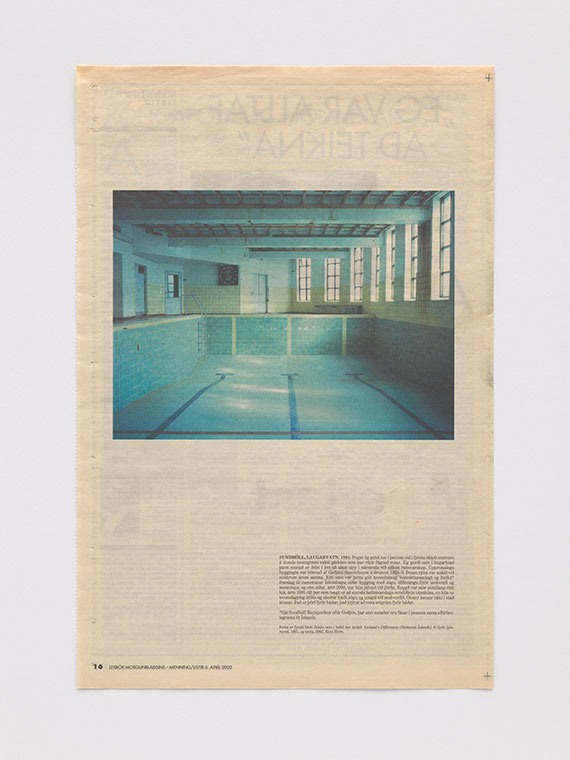

Image credit: Roni Horn, Iceland’s Difference: Lesbok No. 1, 2002, (p. 192). Courtesy the artist and Hauser& Wirth: Ron Amstutz, New York © Roni Horn

Island Zombie begins, “I’m often asked, but have no idea why I chose Iceland, why I first started going, why I still go. In truth I believe Iceland chose me.” Place and the notion of Country, which is so central to Australian First Nations peoples, has been on my mind a great deal since the pandemic began. So many have been displaced and so many have been trying to return to their ‘place’ since it began. You are someone used to moving between two opposite places often – New York and Iceland. Which

of these is your ‘place’? How important

is place for you?

I guess I’ve always thought of myself, in regard to Iceland, as a permanent tourist. So, it has this paradoxical quality of a place that you know you’re going to go to, but you also know that you’re not going to stay. You know you’re going to leave. So that is the ammo that I work with in Iceland. I’ve had a studio there and I did consider living there at one point, but then I backed off. I thought maybe I could make a move towards Europe where most of my audience, or at least my opportunities, are. I do have an affinity for European culture in general. But somehow I was drawn back to the city (New York). I never spent more than six months in Iceland.

You obviously haven’t been to Iceland this year, or have you?

Well, life, my life, has shifted a lot. When

I was really doing Iceland, which was during the ’80s and the ’90s, I would go once or twice a year. I was constantly coming and going. It wasn’t like I planned it. It was just like … I would have some agenda, I had to photograph something,

or I wanted to research important landscape or just go hang out there. That’s what my research is, hanging out in places that just are ‘food’. They’re so fulfilling. But two things have changed since 2008. For one, the economy in Iceland went through the floor. That was, I think, a heavy lesson for the country. But also, they turned to mass tourism. And in my opinion, a very destructive form of it. And I hope they’re going to turn it around. I don’t know.

I can’t get lost anymore. And it wasn’t that I wanted to get lost, but I welcomed the possibility because it’s that edginess that I am always attracted to. That was part of my relationship with Iceland. And then, I decided that I was going to live by the sea and I bought land in Maine. There’s no comparison between Maine and Iceland, but it definitely gives me some of what I get from Iceland. It gives me the weather. It gives me this violent ocean, which I love. And it gives me the space from humanity. Those are the three big factors about Iceland that I’m drawn to. None of that’s changed. It could have been that I wound up buying land in Iceland and hunkering down there, but I felt shy to do that because I felt that I would lose something. You know, the first time you see something it’s a unique experience, you cannot revisit it. But I get that with Iceland every time I go there. I think I’ve been almost everywhere in Iceland. You did ask a question about how Iceland is relative to New York?

And there is a complimentary relationship; neither of them really has trees.

That’s true.

In fact, when I was growing up, one of my favourite things was old trees. But then, I think I could be in Iceland and never miss a tree because there’s something there fulfilling the same need. I was going to go there (in 2020) and hang out in this one location that I love, which also happens to be where my friend (the artist) Ragnar Kjartansson has a house. And I got all excited but then this new mutant COVID-19 strain came on and I don’t feel adequate to keeping it away from me.

So, I nixed that idea.

Your Icelandic works describe place and location very often though absence. You’re obviously photographing what seems to be absence, though you are present in the taking of the images. When I look at those images of Iceland in Island Zombie, they’re almost horrifying because they’re so opposite to where I live in the subtropics with many trees, animals, birds and chatter. Iceland to me seems like this very static, cold place.

I totally get you. Particularly people who grow up in warm places have a really hard time acclimatising to something else. Iceland is still so much about the weather and the landscape, the rocks and the simplicity of everything around me. It’s just … I never get used to it. Every time I go, it’s (like) the first time. Partly because the weather has hidden so much of Iceland over the years. It used to be very rainy, and the clouds often sit so low to the ground that you can’t really see much. And I’ve spent months in weather like that. And then sometimes you go back and you’re in the same place and you see everything.

While you’re known as a visual artist, you’re also someone who writes, and you’re very connected to and interested in writing and poetry, Emily Dickinson specifically. Can you tell me a little bit about that connection of, very basically, words and images?

Well, I guess I walked into that. I’m not sure I’m a visual artist. I’m not sure that’s an appropriate term for me because I never felt that what I was after was purely visual. I always felt it was experiential, which allowed me to pull together aspects of the visible with aspects of the abstract – language, for example. It allowed me to look at the type of experience that reading something versus looking at something (brings) and ask, “Can we have that all together, please?” – distilling the experiences that I like to work with. But I was forced to pick an identity in a way, or it was forced on me. And that identity was visual artist. Which means nothing to me, honestly. And I don’t mean it disrespectfully, because I love visual artists. I’m equally committed to and interested in writing and literature. Journalism is really an important part of my sense of place. That practical observation of the current moment fascinates me as much as a fictional account of war. Right now, I’m reading a book called Stalingrad (1952) by Vasily Grossman.

Obviously what you’re making exposes ideas around environmental concerns. Do you think of yourself as

an environmental artist?

No, I don’t like to add any conditions to my identity. So no, I’m not environmental or artist or a feminist or a colourist or a formalist. I’m none of these things, but I do use some of the languages involved with these various fields, they all sometimes get incorporated into what I do. So as far as environmentalism goes – or, I guess, climate change – Library of Water (2007) is the body of work that I think most people think is based in environmental commentary. Well, of course it has that content in it, but I also wanted to have a visual experience that was very close to air, in the sense that it was invisible or colourless. And so, it’s water inside glass, in a room with an exquisite relationship to the outside. But now the glaciers that I collected (the water) from are gone, but the water (in Library of Water) is still there.

You must have seen an enormous change in Iceland over the years that you’ve been going there.

Yes, that’s a whole story in itself. And what’s funny, Ragnar pointed out that I started going to Iceland the year he was born.

The changes I have seen in Iceland are truly radical. I don’t think they’re unique to Iceland, but it’s the example that I’m aware of. They didn’t really finish paving the major ring road around Iceland till the late 1990s, early naughts. That immediately gave access in a way, and encouraged the use of cars for travel. Up until then it was just a painful experience to try and get around in Iceland.

This new book then, Island Zombie, is it a love letter to Iceland? And I mean, it’s all a love letter to Iceland, isn’t it, in a way?

There’s definitely a lot of love there. A lot of deep, deep … not gratitude, but pleasure in the process of this island. Really, for decades I was going there without any interest in the culture, but that eventually came and I have some very, very dear friends there, which changed the world for me, but it was not really a social experience.

It was a solo experience.

It was very self-reflective, mirroring nature, or I don’t know … I was getting confused at what was the mirror, whether it was me or the nature. Being alone in places like Iceland is not at all like being alone anywhere else in the world in any other way.

Can I ask, why do you want to be alone?

It’s probably pathological, who the hell knows. I have a very high tolerance for just being. Do you know what I mean? Not having to be active or do something, and with (other) people you’re always ... it’s not exactly an agenda, but there’s a quiet, tacit, “Let’s do something.” It’s a distraction really. I never liked to travel in Iceland with anyone for that reason, because it adulterated my experience. I mean, I guess I’m a very selfish person that way. But I wouldn’t change a thing. The first time I really thought that I was betraying my solitude was when Artangel came to me and wanted to do a project in Iceland.

The big thing was trust and it really worked out well. I wouldn’t have necessarily done Library of Water because it involved me working in Iceland with Icelanders. And it wasn’t that I had a problem with that (working with others), but it was just not really what I wanted

for my time in Iceland. Once I got over that, it was an amazing production process because I got to go into parts of Iceland that are completely inaccessible, except with the most skilled drivers – into the interior, into the glacial zones.

It’s not that I’m against social experiences. It’s just that I’m not a very social person by nature. I almost never feel lonely. People always ask me, “Are you lonely?” If I have a beautiful tree in front of me, I don’t miss anything. You know what I mean? Much less if an animal or something wanders across the scene. That’s so thrilling, and I never had a domesticated animal. I don’t know that I will, but I love the presence of animals, both in their beauty and their threat, all of it. Looking back, it’s very clear that I was partly drawn (to Iceland) because there was nothing. I could go there as a woman, although not necessarily obviously as a woman because I’m so androgynous. I could go there and know that I wasn’t going to have to deal with threats or physical violence. There were some weird experiences, but they were more spiritual. It was more like the energy in a place didn’t suit me. And that can be an interesting fear that comes out of something more complex than you know. Nothing happened to me in the place. Sometimes I’ve had experiences in places I thought were weird and mentioned it to friends and they’ve said, “Oh yeah, that place is haunted.” You know what I mean? There may have been something weird that happened, or a lot of people go there and feel that it’s weird too – there’s no actual event that makes it so. But when I was camping, I would sometimes feel the energy. And even though the sun was going down and I was just sitting there,

I knew it wasn’t the right place for me.

What is your life in New York like then? Do you have a similar solitude?

I tend to make commitments and cancel. I really do wish to see what or whoever, but then I’m, like, onto something else and it’s a bad moment for me to leave. And it happens so much that I stopped making commitments because it’s rude.

I did want to ask you, if I may, about your interactions with Félix González-Torres, who I admired so deeply.

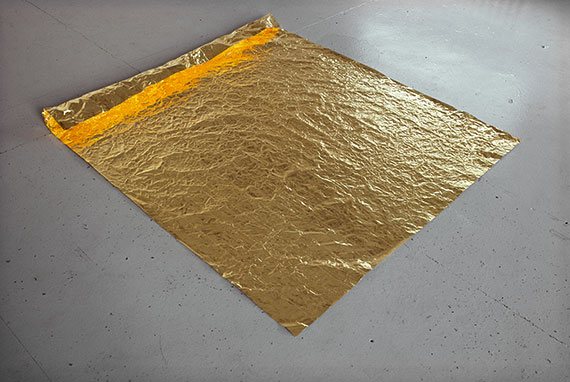

You know, at the risk of distorting that reality, Félix and I were not best friends or anything. We were very friendly when we met each other in 1991 or ’92, somewhere around there. And then we became close, but it wasn’t ... we’ve left a legacy that makes it seem a certain way. I don’t want to distort it and I’m always nervous to talk about it. But I’ll just say that the origin of our friendship started when he and his boyfriend Ross visited a show I did at MOCA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) in 1990, which was the first museum show I’d ever done. And it was the first time I showed a work that I’d actually finished. I’d actually executed the work in 1980 or ’82. And that was Gold Field. And I never had the opportunity to really show it for 10 years. What came back to me was Félix’s love for that piece. He was very expressive about it to me in a way that was really, really special because he triangulated me with Ross, his boyfriend. He was always saying, “Oh, Ross and I, we went to MOCA, we saw ...” And Ross had passed away. In my eyes, I felt like Ross was alive when he was talking to me. And then (Félix) did this work, a placebo (“Untitled” (Placebo – Landscape – for Roni), 1993), which he dedicated to me and then I turned around and did Gold Mats, Paired for Ross and Felix (1994/95). The light comes between the gold sheets (in the work). It’s a really beautiful metaphor for who Félix was and his relationship with Ross, which for me is only imaginary because I never met Ross.

It’s just a beautiful story. It’s a very special and unique thing that happened.

I think I would say that our relationship was really unique and it was very real.

There was no bullshit in it. We were ... Yeah, I really loved Félix.

I tell you what, I really want to go to Iceland now.

Yeah. Well, I take 10% of the tourist income from there.

Roni Horn, A rat surrendered here is on show at Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France until 24 October, 2021.

Roni Horn is represented by Hauser & Wirth, New York and Xavier Hunfkens, Brussels.

chateau-la-coste.com

hauserwirth.com

xavierhufkens.com

Image credit: Roni Horn, When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes, No. 1695 (THERE IS A SOLITUDE OF SPACE, 1993), solid aluminium and black cast plastic, variable length from 108 to 178.4 cm. Photo: Stefan Altenburger. Courtesy the artist and Hauser& Wirth ©Roni Horn

Image credit: Roni Horn, Vatnasafn / Library of Water (Iceland), 2003-07, View shows: Water, Selected. 24 glass columns, each holding approximately 53 gallons of water taken from unique glacial sources throughout Iceland. Each column 304 x 30.5 cm. Overall: 93 m2 You are the Weather (Iceland). Solid rubber with rubber inlay text. Each tile 3.2 x 122 x 122 cm. Overall: 139 m2. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth ©Roni Horn

Image credit: Installation view Roni Horn, Gold Field, 1980/82, Artist’s Space, New York, 2013, 99.99% pure gold, 1245 x 1524 x 0.2 cm, 0.8 kg. Photo: Daniel Perez. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Roni Hornn

This article was originally published in

VAULT Magazine Issue 33 (Feb – April 2021).

Click here to Subscribe