Dale Harding: The creek is nourished by many sources

Dale Harding’s multilayered works draw upon connections between modernism and Aboriginal culture to propose a new model of practice.

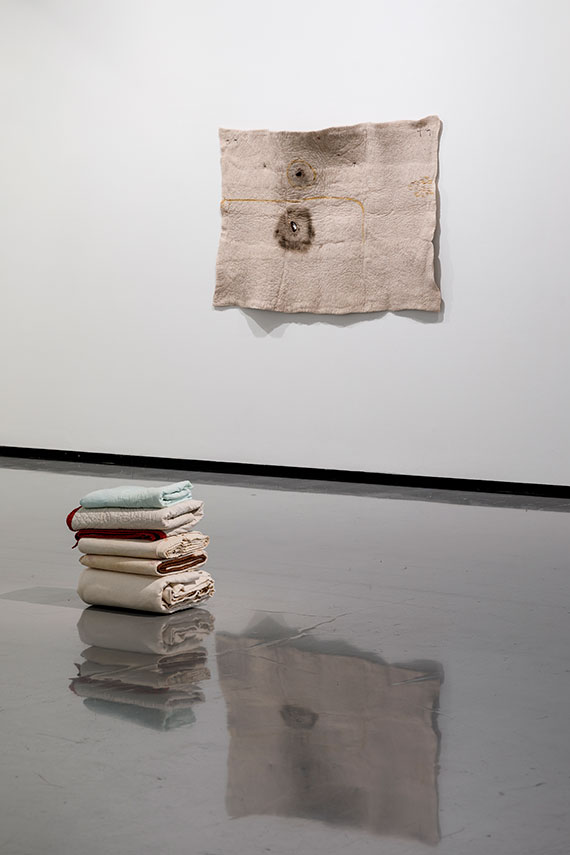

Image credit: Dale Harding, Extractive painting 2, 2021, Dale Harding: Through a lens of visitation at Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

At the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), there is a fascinating collection hang tracing the survival of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural practice over more than two centuries of dispossession and displacement.1 Among several displays of historical objects is a series of carved and incised hardwood clubs from the late 18th century, attributed to unknown Murri (Queensland Aboriginal) artists. Their elegant, monochrome forms are echoed in an adjacent installation by Dale Harding (born 1982), a Queensland artist of Bidjara/Galangu/Garingbal ancestry. Harding’s Body of Objects comprises a series of similar nulla nullas (clubs), as well as boomerangs and spears, although his contemporary versions are cast in black silicone. The flaccid forms of Harding’s objects are draped over the edges of plinths of varying height and dimensions, referencing the topography of Carnarvon Gorge in central Queensland, his mother Kate’s Country.

Made in 2016 and subsequently expanded upon for the artist’s presentation at documenta14 in Athens and Kassel the following year, Body of Objects is a formative work in Harding’s oeuvre that also foreshadows the artist’s increasing focus on the reinvigoration of culture. Having majored in sculpture at the Queensland College of Art (he is a graduate of its prestigious Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art program), Harding’s practice has evolved in recent years to encompass wall drawings and works on canvas made using natural pigments and Reckitt’s Blue, the powdered laundry detergent popular in Australia during the colonial period. Harding’s use of the material recalls the domestic labour his matrilineal ancestors were forced into under Queensland government control. His drawings on gallery walls can be seen as a continuation of the informed traditions of his forebears, who created artworks on the sandstone rock of Carnarvon Gorge and surrounds.

In addition to documenta14, Harding’s work has been curated into significant international exhibitions including the Liverpool Biennial 2018: Beautiful world, where are you?; Surface Tension, Sharjah Art Foundation, United Arab Emirates, 2019; and the 15th Lyon Biennale: Where Water Comes Together With Other Water, France, also 2019. Harding’s work has been acquired by major collections including The Art Institute of Chicago and the Tate, Britain in conjunction with the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. One of the reasons that Harding’s work has resonated so strongly in a global context is the way in which his practice explores aesthetic connections between modernism and Aboriginal culture. Two recent institutional exhibitions illustrate how Harding is both documenting these transcultural connections, as well as positing a new mode of practice that draws upon the artist’s Aboriginal heritage and connections to Country, as well as his Western art education.

His most recent exhibition, Through a lens of visitation (2021) at the Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), considered Harding’s relationship to his mother’s Country around Carnarvon Gorge. Curated by Hannah Matthews, the project comprised three distinct parts, reflecting the artist’s collaborative and research-based approach. This included a selection of new and recent works on canvas, as well as felt and glass objects. For Extractive painting 2 (2021), one of two new works made for the exhibition, Harding saturated a linen canvas with dry red ochre pigment and gum Arabic. The resulting monochrome features variated segments of ochre, the darker sections indicating where the pigment has been thickly applied. Extractive painting 2 exemplifies what Harding has termed generative art, for which he provides the following definition: “What can I do, that can grow more?”2 By applying a brush and water, Harding can reconstitute the ochre and transfer it to another canvas or board, thus generating another work and another and so on, until he has exhausted the pigment. In this way, Extractive painting 2 evokes the process of mining pigments and other natural resources, and embodies the conceptual and performative nature of the artist’s painting practice.

Alongside Harding’s work in the exhibition was a series of quilts by his mother Kate, an accomplished textile artist. Having previously made domestic, functional quilts based on American and Scandinavian traditions, Kate Harding has recently shifted focus to address her own Country and family history, using ochre dyes and Aboriginal techniques. As a child, Harding was taught to sew by his mother; his first solo exhibition comprised a series of needlepoint embroideries and textiles have continued to play an important role in his work. Showing together for the first time, strong formal and familial connections were made evident.

The exhibition was accompanied by a publication featuring newly commissioned texts by art historians Deborah Edwards, Ann Stephen and Nancy Underhill exploring the connections between modernism and the history of the Gorge, including artists Sidney Nolan and Margaret Preston who both visited in the 1940s. As Stephen notes in her essay addressing Harding’s relationship to minimalism and conceptual art, “Harding’s abstraction is never purely aesthetic, being socially invested in Indigenous culture and history.”3

Stephen’s observation also speaks to the objects and materials Harding is presenting in There is no before at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth until mid-August 2021. Alongside an Extractive painting, the artist is debuting a suite of small monochromes on glass panel made using store-bought red ochre, an acknowledgement of the pigment’s status as a commodity that is mined and traded. In addition, Harding is showing a new textile work, a 10-metre bolt of couture-grade silk that the artist has dyed using tannins from the beefwood tree found on his family’s Country in central Queensland. Red dyed textile work (2021) has been suspended from the Govett-Brewster’s curved concrete walls, spilling onto the floor. Both sculpture and textile, it’s another iteration of the artist’s ongoing experimentation with the codes of minimalism as well as traditional materials and processes.

For the artist’s first solo exhibition in Aotearoa New Zealand, curator Megan Tamati Quenell has also sourced 18 clubs – many from central Queensland and of the same lineage as the objects currently on display at QAGOMA – from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Harding has installed the historical objects above standard height, affording them the elevated status normally given to artworks. Conversely, a selection of the artist’s studio materials, including Reckitt’s Blue, Lapis and red ochre, are displayed in museum vitrines. There is no before challenges traditional categorisations of contemporary art and cultural practice, showing them to be equal parts of a greater whole.

Viewed together, these recent projects demonstrate Harding’s inclusive and pluralistic approach, one that seeks to share knowledge and emphasise connections across Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cultures. As the artist notes in his poetic introduction to the Through a lens of visitation publication: “The creek is nourished by many sources.”4

Through a lens of visitation will tour to Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney in February 2022.

Dale Harding is represented by Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

milanigallery.com.au

1. I, Object, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art,

Brisbane until August 20, 2021.

2. Interview with the artist, May 6, 2021

3. Stephen, Ann, ‘Beyond trauma narratives,’ Dale Harding:

Through a lens of visitation, Monash University Museum

of Art, Melbourne and Powered by Power, University of

Sydney, 2021, p. 53.

4. Harding, Dale, ‘Bidjara Garingbal Karingbal,’ Dale

Harding: Through a lens of visitation, 2021, Monash

University Museum of Art, Melbourne and Powered

by Power, University of Sydney, 2021, p. 1.

Image credit: Installation view, Dale Harding, Extractive Painting 1, 2020, in There is no before, 2021, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Aotearoa, New Zealand. Photo: Sam Hartnett. Courtesy the artist and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Aotearoa, New Zealand

Image credit: Dale Harding, There is no before, 2021, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Aotearoa, New Zealand. Photo: Sam Hartnett. Courtesy the artist and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Aotearoa, New Zealand /p>

Image credit: Installation view, Dale Harding, What is theirs is ours now (I do not claim to own), 2018, Reckitt’s Blue, ochre, dry pigment and binder on linen, 2 parts, each 180 x 240 cm, 180 x 480 cm overall in Dale Harding: Through a lens of visitation, 2021 Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis

Image credit: Installation view, Kate Harding, Birth and ten-year-old quilts, 2021, textile and wadding, displayed folded, dimensions variable; Dale Harding, Cloaks (mortua and mortuus), 2018, gum arabic and powdered pigment on cotton blanketing, displayed folded, dimensions variable; Dale Harding, Repression cloak (ceremony for a gay wedding), 2018, synthetic powdered pigment, ochre, gum arabic, abrasion and pressure on cotton blanketing and nails displayed folded, dimensions variable; Dale Harding, Untitled cloak, 2018, dry pigment and gum arabic on cotton blanketing and nails, displayed folded, dimensions variable; Dale Harding, F1 (Saddler’s contract), 2020, wool felt made by Jan Oliver, gum arabic, yellow ochre, scorching and nails, 104 x 162 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett. Courtesy the artist and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Aotearoa, New Zealand

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 35 (August – October 2021). Click here to Subscribe