Q&A:

Jordan Wolfson

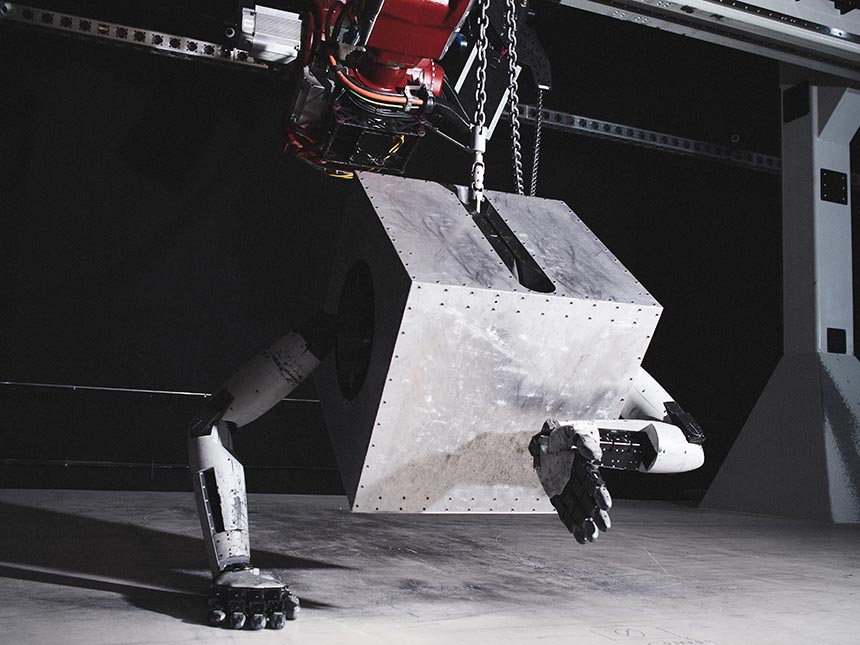

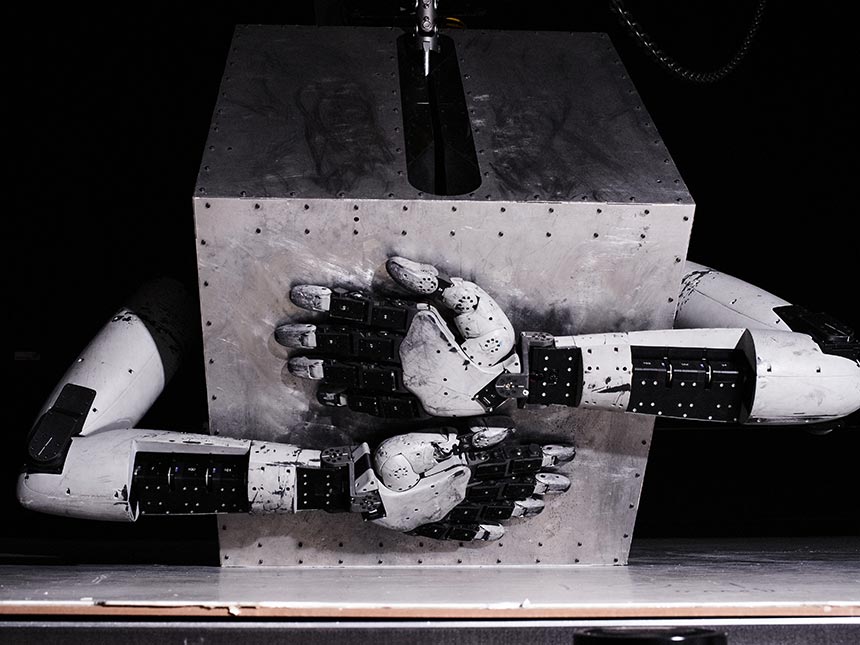

Jordan Wolfson wants you to like him, and well, it’s not difficult. He’s an excellent conversationalist, deeply curious, fastidious, ambitious and thoughtful. He takes time to formulate his answers. He thinks deeply. One of the most fascinating and provocative artists of his generation, Wolfson is ultimately preoccupied with what it means to be human, as explored through works of striking complexity and technological brilliance. Ahead of the unveiling of his new work Body Sculpture (2023) VAULT spoke to Wolfson about consciousness, Buddhist mindfulness and the positives of AI. Body Sculpture will be shown alongside works selected by Wolfson from the National Gallery of Australia collection, offering audiences further insight into the artist’s innovative vision.

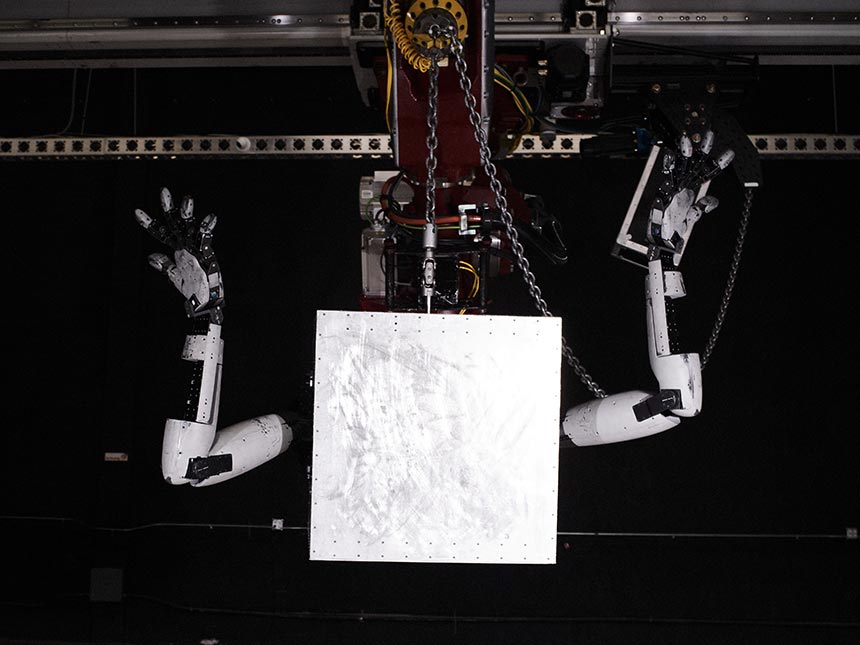

Image credit: Jordan Wolfson, Body Sculpture, 2023, National Gallery of Australia Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019 © Jordan Wolfson.

Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner

Photo: David Sims

Are you very jet-lagged?

I’m pretty tired.

Is it your first time to Australia?

Yeah.

And are you now realising why people come here for more than three days, because it’s a really long way?

Yeah, I’m very tired.

You feel like it’s going to be a good home for the sculpture?

I think this museum is so beautiful. It’s very cool. I didn’t know how dramatic the museum itself was going to be.

The architecture is pretty amazing.

Yeah, I didn’t understand how dramatic the architecture was. I knew that it was a dramatic building, but I didn’t know the scale of that.

Let’s talk a bit about the sculpture and the length of time you took to make it. And I believe the ship is here. Is that right? And it’s ready to be unpacked?

From what I understand, it’s arrived, yeah.

So, what is that like for you? Are you going to be here when it’s unpacked and at what point do you finish and hand it over? How do you know when to stop?

The artwork will be installed more or less without me. And then I’ll arrive probably in the middle of November, and I’ll work on this group exhibition from the collection. And then I have a little bit of polishing to do on the sculpture itself. And then I will work on the choreography of the viewership of the sculpture. And then I’ll oversee the exhibition probably a week after the show opens to the public to make sure everything’s running smoothly.

How many things are you working on at any one time aside from this work?

I was able to have a few side projects but as the completion date came closer and closer, I cut out all distractions. I can’t work on more than one thing at a time so when I do split up the time I’ll section off days or half days and jump between different tasks. With Body Sculpture, initially there was a lot of delay and waiting so I was able to produce other work, and even shows, while the vendors and fabricators were busy. When we got close to completion, I was still able to work on other things and I’d be called in to look at stuff. At the very end though, I cut out all the other work almost ritualistically to just focus on Body Sculpture, but somehow that wasn’t completely productive because it created a lot of nervous energy and gaps of nothing to do while I waited for the technicians to be ready for me.

How do you arrive at new ideas or new work?

I don’t actually get new ideas while I’m working on a big project like this, which I’ve always found strange. It’s like my mind is closed. I heard David Lynch talk, and he said the desire for an idea is like an invitation for the idea to come, so when I’m busy with a work, particularly at this scale, new ideas aren’t welcome and I’m only really creative in relation to the work in front of me. There aren’t sudden drops or downloads of new ideas.

Probably your brain is full while you’re working on something.

Yes, I’m not open to any new ideas unless those new ideas relate to what’s in front of me. pertain to my focus.

And then I guess with something like this, which is different again to the other sculptural iterations, the technology is extreme. Can you talk a little bit about that process? Is it sort of superseding itself as you are doing it?

In the case of this sculpture, we had the technology from 2020 up until 2023. It hasn’t changed that much, but we’ve written a lot of software to support the choreography. This work is pretty sophisticated and a lot of what I wanted wasn’t possible and a lot of what I thought would work formally didn’t. But I wasn’t disappointed, just forced to veer in different directions constantly and sometimes I thought I’d be sad but actually I was relieved when things failed, or sort of tickled by it, because you think you’re having a battle with technology, but you’re really just having a straightforward dance with art which is totally classical and formal and the same as with any other artwork. The illusion is that it’s different because of the technology, but it’s not. That was the lesson knock me over the head.

It’s that interesting thing about when you drive by a new car and then you drive it off a lot and it’s almost immediately redundant, it’s already lost its value – which is not to suggest your sculpture has. But that thing about putting something in place with all this technology but it’s changing so quickly. Will it have the opportunity to grow and change as a sculpture? To upload its technology, as it were?

I don’t know. Potentially yes, I think so. It’ll need to have that. But I’m mostly just consumed with the present moment, which is probably a little selfish and unprofessional of me.

No, I think that’s interesting. Anything to do with technology is so rapid.

If someone said to me, would you be worried about no one remembering your art after you’re dead …

I was going to ask you that question.

Well, the answer is no, I’m not concerned with that.

Why? Because you will be dead?

No, because that’s ego. It’s just silly and kind of laughable. I want to enjoy myself right now. Also the future is bright and there will be 3D printers running on AI that will help me print any part of this sculpture in the future.

Obviously, your work is very experiential. I read something where it was described as ‘event art’, which I thought was just about the worst phrase you could use to describe anything. But it does have an interactive element. Can you talk a little bit about that performative aspect?

Sure. I actually don’t like interactivity.

I think there’s a part of our brain that’s for listening to music and looking at art. And there’s something about those two activities where the viewer becomes passive. There is another part of us that tells us to perform or serve others. I find that we switch between these roles. For whatever reason, I’ve found that interactivity shuts down this passive side in the viewer and they become stimulated in a pragmatic way, like how you might feel speaking to the operator on the phone or finding directions. It’s all pretty convenient if you think about it, but I don’t like interactivity for that reason, it removes the viewer from their witnessing state and over-stimulates them.

“I think there’s a part of our brain that’s for listening to music and looking at art. And there’s something about those two activities where the viewer becomes passive. There is another part of us that tells us to perform or serve others. I find that we switch between these roles. For whatever reason, I’ve found that interactivity shuts down this passive side in the viewer and they become stimulated in a pragmatic way, like how you might feel speaking to the operator on the phone or finding directions. It’s all pretty convenient if you think about it, but I don’t like interactivity for that reason, it removes the viewer from their witnessing state and over-stimulates them.”

So the way then that your sculptures perform, as it were, is that sort of how you think of them?

What do you mean by ‘think of them’?

Image credit: Jordan Wolfson, Body Sculpture, 2023, National Gallery of Australia Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019 © Jordan Wolfson.

Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner

Photo: David Sims

I think I just anthropomorphised the work. Do you do that too? This is probably how robots will become sentient?

I try to bring the work where I feel it. Mostly it looks clunky and dull to me and I try to push it to become alive, or something other, but I don’t see it as alive initially, and I’m not tied to it emotionally – but maybe the results would be better if I were. It’s just hard, because I’m looking at everything so critically all the time, and everything must be activated all the time, and if it’s not, I’m frustrated.

How do you move past that then?

As an artist you have to reground yourself over and over again and simply find out what works and what doesn’t. It’s like every artwork has its own alphabet and you need to relearn and write a song or poem with it. Or, instead, maybe each artwork is like a broken car that’s delivered to you, and you have to invent a way to fix it. It’s endlessly difficult and annoying and demoralising. It’s insanely hard but the feeling of getting it trumps all the suffering and then in hindsight the suffering was really good.

So then is the ‘robot’ – that term feels not quite enough to describe it – an avatar for you, something other?

No, it’s not an avatar for me. I had these experiences with a stimulus that was moving from a very early age. And I probably have a kind of aptitude for things that move or making things move, for whatever reason, I don’t know. I remember when I was 11 or 12 standing on a small concrete river dam in Connecticut where I grew up. The water flowed over the dam so smoothly and perfectly it almost didn’t seem real, and I remember pushing my hand into the water and manipulating it, rolling over my hand, and I think I stayed there for an hour or so just making variations of this completely hypnotised by this perfect movement. It’s hard to explain but this was incredibly profound for me and either something woke up in me or something changed during this experience, and it has remained one of my strongest memories from being a kid. I felt it relate to me in a way before I knew I would be an artist and I still think about it all the time.

This sounds like a ridiculous question, but if you could make a robot of yourself, would you?

No.

No?

No.

I just realised yesterday for the first time that I’ve never actually ever used ChatGPT. Everyone around me is using it, and as an editor and writer and curator, it was such a strange realisation. Do you use ChatGPT, or is it something that you are exploring?

I’ve played around with ChatGPT, and I’ve used DALL-E and other AI image generators in my work. I like it and there’s a certain gestalt to both the images and text it generates that is sort of charming but already that feels old to me, that it has this kind of generalised voice or generalised perversion that feels like it will get stale very soon and simply become the ‘robot eye’. I think the trick will be not relying on it aesthetically but using it as a bridging tool to bring different technologies or tasks together. But just like movies were in the ’90s, and then the internet in the 2000s, AI will be the next illustrator of our collective unconsciousness. And I’m positive that, like all those previous trends showed us, looking directly into the eye of that thing only bears fruit temporarily.

Yeah, I think it’s very interesting because I’ve got three kids, teenagers, and they’re sort of interested in this thing and simultaneously completely disinterested. It’s such an interesting thing to see it from their perspective. I find they’re going more analogue, which is interesting to me in terms of how they want to do things, like read books or listen to music or whatever it might be. They’re choosing that much more analogue method. So perhaps, I agree with you. It’s all science fiction, all the things that I think we fear about it until such time as they do rise up and kill us in our sleep. But with this work that you’ve made, in terms of the programming, I know it was an incredibly complex process, wasn’t it? You have worked with scientists and engineers, and I know there’re some experts from the Australian National University who are going to assist as well with various programming. Tell me a bit about what that process is like for you as an artist. Is that something you just relish, that opportunity to work with people outside your field?

Yes. I relish it. There is something about working with people outside of the field of art that forces me to be on my best behaviour. It’s like meeting your girlfriend’s parents. It’s important to make a good impression and continuously create a productive and novel experience with them while at the same time carefully choosing what to reveal and what to hide in terms of the sacredness of the art practice. Also, it’s important to establish boundaries. If you do this correctly it can be great; if you fail it will be a disaster and incredibly painful and humiliating. There needs to be a sense of unity and mutual respect and also distance and in a way, you give them the opportunity to become like an actor working with you as a director and the ultimate gear becomes trust between you both.

Just kind of telling them what you’d like to achieve or … ?

Yes, but it’s more of trying to get them on board to experiment with me and for them to understand that the process is about the discovery rather than me being able to say exactly what I want. Throughout the work I kept explaining that we needed to make tests upon tests and that I’d know what to do ‘when I saw it’. Once they accepted this, they fully supported me because the expectation was set.

In terms of the things that Body Sculpture does, can you talk a bit about those things and what you want it to do?

I guess looking back at it, the work kind of attempts to talk about how it feels to be a person and all the primitive qualities about ourselves.

The base level.

Right. You know that there’s a type of pleasure within us, instinctually, to be at once the audience and the performer. Like anything, it couldn’t exist without its opposite and needs to flip between the two. So, the artwork tries to show that. Good and bad, light and dark, and audience and performer.

Because the work literally points someone out, doesn’t it?

Actually, it doesn’t do that anymore.

It doesn’t do that anymore, okay.

No. We could have done that, but it just felt wrong. It didn’t feel right to do that. It felt interactive in a negative way.

As you were speaking about before.

I took that out, but that wasn’t something that I could anticipate being negative. I anticipated it being generative and then it was subtractive. If felt sticky and bad and blah. It was one of those funny moments where you toss out an idea you’ve been committed to for five years in five minutes because you just see it finally come together for the first time and it falls flat. I did get it to work in one way, but it ultimately wasn’t technically possible, so I made do and dropped it.

Your work is incredibly ambitious in scale, but is Body Sculpture different again from Colored Sculpture, for example?

They are relative in size actually. The thing is that I have this delusion that if I have an idea for something, then it must be possible, or some version of it must be possible. And, for better or worse, it’s this thinking that has led to this scale of production and complexity.

So, I guess then the question is does it match your original ambition? Maybe only time will tell.

I never had large-scale art ambitions, mostly I had romantic ambitions of the life of an artist but once I left painting and moved into video art, I saw that an artist could be a kind of scientist and I had a rough plan of being a sort of cultural critic scientist, but never at this scale. It feels like this all just happened by accident. It’s one of those ‘don’t look down’ moments because once you do you lose your grip and fall to your death.

Image credit: Jordan Wolfson, Body Sculpture, 2023, National Gallery of Australia Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019 © Jordan Wolfson.

Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner

Photo: David Sims

What does the creative process look like for you? You clearly take your influences from a wide range of things. You said ideas come to you in blank spaces of time?

It’s all really intuitive. It’s just like listening with my body and not my mind because my mind is really just trying to keep me out of danger and protect me and help me survive. But when I listen with my body, things can just happen really, really quickly. And I need to be able to trust that and have a mastery of knowing when an idea is good. And it (the artwork, or idea) is not good because it ticks a bunch of boxes, it’s good because it carries a kind of frequency and feeling. And being able to trust that frequency and trust that feeling from that idea and then executing that idea with a high frequency.

A frequency that you can hear, that is for you.

That I can feel, and I can trust. And that took a long time for me to learn, and I’ve also forgotten it and had to relearn it.

That’s very interesting, learning how to trust the feeling and the first thought you have and try and realise it.

For me, it’s like looking at myself as a maker in the present moment, from a completely uninhibited non-judgmental perspective, and hoping my mind stays open just long enough for something productive to happen. Then when my mind closes, I look at myself from outside of myself, remembering the quality of the feeling I had when I was in that open state and trusting that – no matter how much fear, doubt and insecurity I feel. It’s like going on a journey knowing where you are, remembering you know, then getting inevitably lost, then remembering that you once knew and just trusting the memory of remembering. Trusting the calm mind. That’s all.

Do you think of yourself as something of an autodidact??

I don’t know how to do a lot of things. Most things I can’t do but I’m good at communicating with people who can do those things. And that’s something I’ve taught myself.

Because it’s a collaboration?

Sure. I’ve been able to develop my work and become comfortable doing my work through the support of other artists or technicians and et cetera.

In terms of your influences, are you influenced by other artists or books?

Sure. So much.

Do you read a lot?

I try to read or listen to books constantly. I love podcasts that aren’t opinion based but more information based. I’m influenced by so many things, and a lot of times I’m just amazed at other artists’ ability to formally solve problems in ways that I couldn’t have imagined. For example, the way a film ends, or a film begins, or the way a song starts.

I always think about that with songs, how do they know when to start it?

I was listening to this song by R.E.M recently, it’s called ‘The End of the World’. And the first line of that song goes, “That’s great,” and then it goes:

“It starts with an earthquake.

Birds and snakes, and airplanes

And Lenny Bruce is not afraid.”

And I just thought, wow! Starting a song like that, “that’s great,” how formally interesting.

It’s sort of a serendipitous thing, but it just works.

“That’s great …” I want to play it for you, so you just know it.

What a great band.

And then the lyrics go, “Lenny Bruce is not afraid.” There’s no rhyme or reason – it’s just about a feeling.

Listen [PLAYS SONG]. And then he goes, “Lenny Bruce is not afraid.” And then he mentions Lenny Bruce again in the song.

You should ask him why.

But there’s no reason, it’s just about a feeling.

That’s the best kind of art.

There’s this need to perform and be the performer and be the audience.

Do you feel like that now? I mean you are Jordan Wolfson.

What do you mean by that?

Well, you are a famous artist now. How does that fame sit with you?

Fame doesn’t really sit anywhere with me. It’s useful, until it’s not. I think being preoccupied with fame and status as a serious maker is impossible because as a serious maker you’ve got to shed what doesn’t matter. So, the idea of being famous is kind of amateurish … but instead I’d like to think of myself as a serious person who is still ‘new’.

That’s a nice thing to say. When you say that, do you mean just the act of being an artist, that it’s making art and everything’s new?

In Buddhism they teach this idea of having a beginner’s mind, and on a good day I have that. And I’m just like, I’m not cynical, I’m excited. I want everyone here at the gallery to like me and feel good. Do you know what I mean? I want to do my best job. I want everyone to like me but not at the expense of me doing my best work. So, when I’m clear, everything still feels new to me. Every relationship personally feels new, professionally, everything just always feels new to me.

It’s a great way to go through the world.

It’s a practice. I don’t always feel new.

We just spoke briefly about Matthew Barney. He’s so interesting to talk to. His work is so complex, elegant and obscure. It all makes sense in his head. It’s all there. And then he constantly has to explain it, which is probably what I think you must feel like too. But he’s trying to explain to you something that makes complete sense to him. As a viewer you just want to get into it, but on some level you’re never really going to get it. But it’s such a delight to talk to him because he’ll describe at length, finding a tree and casting it in bronze. It just strikes me that in a way you are not concerned how the work is received, are you? You don’t want to control its reception.

I’m amazed that Matthew enjoys that, and I appreciate it, but I just don’t have that kind of intellectual or historical unpacking of my work. I really don’t care about anything specifically, except the quality of the experience – not that Matthew doesn’t, but he must get to it in another way than me. But I do care about how it’s perceived because I am a sensitive person and I’m human and have an ego, but I try to talk to myself and talk myself out of caring too much or spiraling. I say things a lot like, “I’m just feeling self-conscious,” or, “I’m just afraid,” or. “I’m tired that’s why I’m paranoid.”

Image credit: Jordan Wolfson, Body Sculpture, 2023, National Gallery of Australia Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019 © Jordan Wolfson.

Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner

Photo: David Sims

It’s hard being an artist. Do you like the process?

There’s always a moment when I’m working and suddenly I’m like, “Oh my God, making art is so hard.” And I say that and people at my studio just laugh at me, and I say it and they’re just like, “What’s he talking about?” I’m like, “Making art is so hard.” But also, by saying that in a way you celebrate it because if it wasn’t hard, it wouldn’t be worth it. It’s crazy hard. And when I decided to become an artist, I didn’t know how hard it would be to make a professional career of it, and I didn’t know how hard it would be to make it, not make ‘it’, but make art. Making art is so difficult.

Yeah, it is though, right?

It’s so difficult. It’s so difficult and painful. And there’re some people who love it and they really enjoy working. And there’re some people where it hurts to do it. And I’m one of the people where it kind of hurts and I wish I could be the other, but I don’t know how.

But maybe you wouldn’t be happy if it was easy.

I think some people enjoy the making and it’s very soothing, but for me it’s not at all soothing.

That’s interesting. You’re kind of in this epic battle with needing to make things that cause you great anxiety.

They don’t cause me anxiety. It’s like you’re wrestling with something that you have to surrender, to set free and watch it accelerate.

Yeah, and that’s interesting, isn’t it? We go into galleries and museums and look at the artwork, but so much of the work is the process that no one sees. The actual artwork is the process, the whole making.

The joy of it is the making and that joy is the suffering. It’s like being in love with someone and the joy is all the pain and all the pleasure and all the laughing and all the crying and that’s the journey.

When you look at Colored Sculpture, do you want to change things, or can you just say that is that?

Wow, I don’t know. I don’t really ever want to change anything. I just sort of look back and when I see those works, I’m kind of talking to the version of myself who made it.

You probably remember the songs you were listening to at the time, what was going on.

It’s more like being an athlete and then seeing an athletic performance from the past. And then I get very insecure wondering if I’m as good as that athlete was in his 30s. In my 40s am I as good as I was in my 20s? And then I can become quite insecure and paranoid about that. So, I try to engage as a kind of artistic technician, to support those works rather than looking back and engaging in them.

And yet it is this unique kind of thing because it’s the thing that leads you to the next thing, to make the next thing. Do you know what you’re working on next?

I have a new piece that I’m working on and hopefully a string of shows at European institutions.

Do you get tired?

Yeah, I get really tired. I’m really good at not working.

What do you do when you’re not working,

Not work. I like nature, and I have a dog. I love coffee.

Do you see movies? Do you kind of look at art?

I’m not into new American movies, but I like some new cinema and I like historic stuff like Fassbinder, Bergman, Buñuel, etc. I love looking at art but since Covid-19 I’ve stopped visiting museums as much.

I like to look at old art now.

Yeah, I love old art.

Which sounds terrible because I obviously like to look at yours too, but I actually really do like looking at old art. And I wish I could go back and be young me, doing art history again, and just study the Renaissance and just pay more attention at the time.

Yeah, as a young person I found all of that art really boring, and it was just a burden sometimes to learn about it. But then as I got older, I started caring more about Caravaggio than I did about whoever from the 1980s. My mother just died and what was interesting about that is my inability in my mind to understand that this person who was so alive, charismatic, had a voice, looked through her eyes, looked into my eyes, looked at me, that she’s gone. What I’m basically saying is this idea that her consciousness has been extinguished permanently or has gone somewhere else. What’s so profound is this idea of consciousness and the representation of consciousness. And so, if you see a Caravaggio, it is radiating with the consciousness of the person who made it. And for us human beings, for whatever reason it’s hard for us to really reconcile that someone was conscious hundreds of years ago because we’re like, “Well, but I’m conscious now and I can be the only consciousness.” But you don’t understand that consciousness was then, and consciousness is in the future, and the only difference is ours is in the present. And it’s the same thing if you see a dog express shame or embarrassment, you’re reminded that you’re not the only one who has this. It’s the representation of consciousness.

Not much has changed. It’s just that we forget to talk about it because we don’t live in a world that encourages intellectual discussion anymore about things, like what it means to be alive, just to be alive.

I think there is a lot of discussion about it, it’s just not practical and there’s a lot of separatism with those discussions and it’s more useful to dissect art for its topical qualities.

In the art world we live in right now, there’s this thing that art has to be about something all the time. It’s got to relate to something or have a political agenda. I know you are not so keen on that kind of prescriptive notion of what arts function might be. It’s not something that you care too much about.

I don’t know. It’s just that in my experience, art could be made from anyone. And if it’s good, it’s good because it expresses consciousness and expresses the conditions of being human. And how it gets there doesn’t really matter.

There’s an authenticity. I was thinking about when you played me that song just then. There are so many great songs in the world. I always say to my kids, “If you only ever wrote one good song, one really good song, you should be so delighted with yourself.” But some people write lots of good songs and then some people only write one good song, but one good song is the best. You’ve just done something amazing. It’s a bit like art. I haven’t heard that song for a long time. I forgot how much I liked that song and how well that song holds up. It really holds up. That’s kind of the challenge with art, isn’t it? How things endure.

Well, you can’t really think about it.

No. Is it like luck?

No, it’s not luck. It’s sad, because if you give the maker the right conditions, they can continue to be creative and have formal successes over and over again. But if the conditions are bad, like drugs, ego, bad advice, etc., then the artist won’t have the opportunities to successfully create any longer. It’s about self-mastery and commitment and resilience. For me, I’ve been almost swallowed up multiple times along the way. It’s most important to remember that the success of the work isn’t the success, instead it’s the freedom. Freedom is the success.

That’s very true. It’s a very powerful thing.

Yes. It’s about the freedom that is delivered and the freedom that is delivering. It’s about being free.

How old are you?

42.

I just turned 50. It’s quite a moment. That’s like half of a 100 years. How did that happen? It’s great if you can get to that point at 42.

Oh, yeah, I’ve been at this for a while. But it’s a practice, not some enlightened state … I try to be free and find success in that and I just want to be kind, to other people and me. And I just want to enjoy being in the world and to feel new, like we said. And yeah, I practice trying to be free. I can only imagine how other people feel or don’t feel. I can’t speak for anyone else but myself.

That’s beautiful. We can end it there.

All right, end it there.

Body Sculpture shows at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra from December 9 to April 28, 2024.

nga.gov.au

Jordan Wolfson is represented by Sadie Coles HQ, London; David Zwirner, Los Angeles; and Gagosian, New York.