Ten Thousand Suns with the Artists: Nikau Hindin

The 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, closed on Monday 10 June after a three-month run beginning 9 March. VAULT spoke to some of the artists involved with the Biennale’s visionary partner, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, through their landmark commissioning of 14 First Nations artists from around the world.

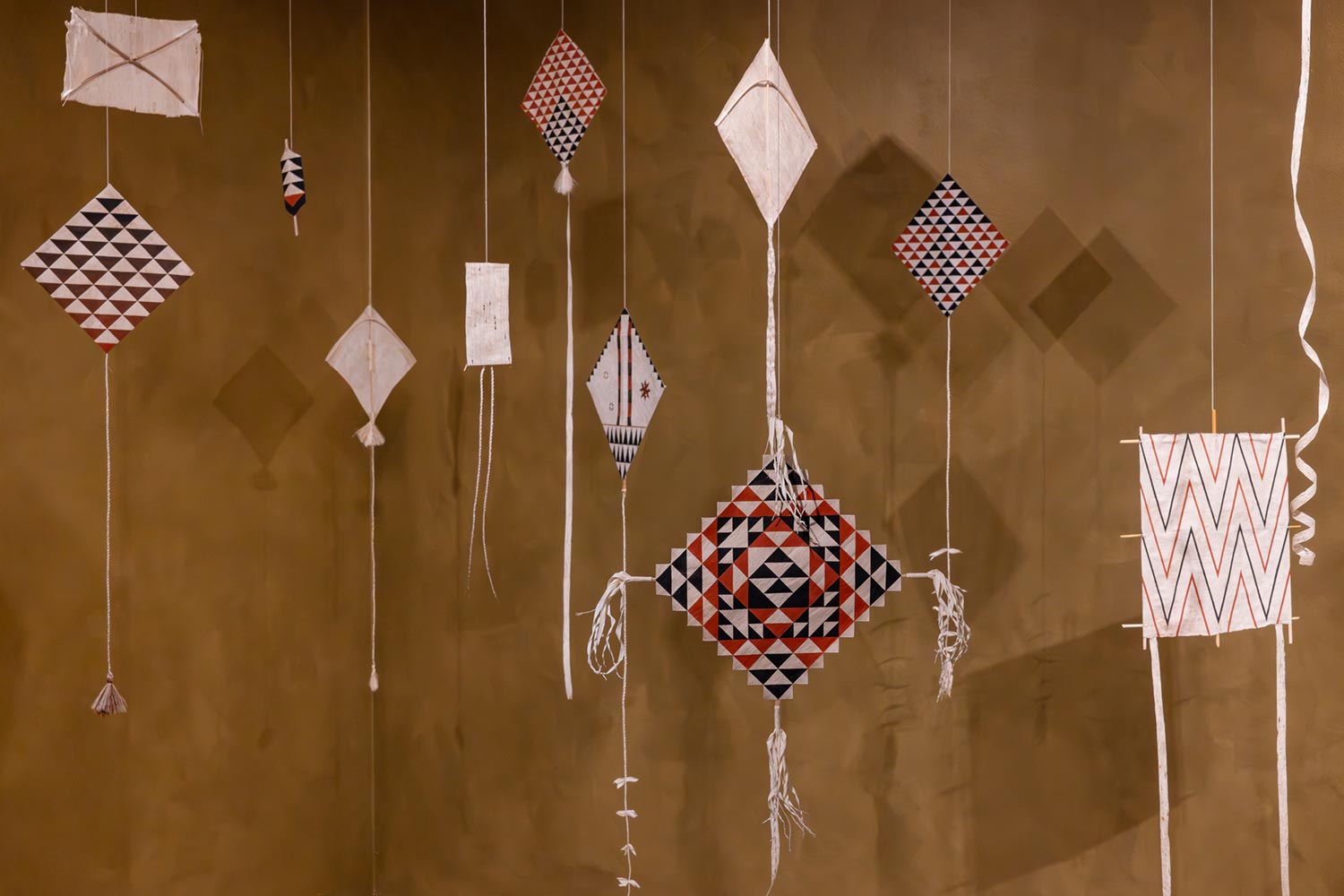

Image credit: Nikau Hindin, Kites, 2022, Installation view, Ten thousand suns, 24th Biennale of Sydney 2024, UNSW Galleries. Photo: Jacquie Manning. Courtesy the artist

Alison Kubler: Congratulations on participating in the Biennale of Sydney. Can you tell me a little bit about that experience and what it's like to be part of such a major survey?

Nikau Hindin: It was pretty life-changing to be part of this project. Fondation Cartier and the Sydney Biennale were really supportive of all the projects I was involved in.

I represent two lineages in my work. The first is I whakapapa back to toi Māori, and toi Māori is our art form. I stand on the shoulders of amazing artists like Rangi Kipa, Brett Graham, Robyn Kahukiwa, and Mataaho Collective, and a highly developed lineage of Māori art forms that come from our land, from our observations, and from our relationship to our whenua, our land.

These all manifest in our patterns, carving, weaving, design systems, our waka, and our oral literature – even our architecture! I think our conceptual thinking is highly developed, and we can trace our ancestry back to the beginning of time, but our conceptual thinking extends as far forward as it does back. Where I stand is that intersection of where the past and the present meet.> My role is to create and draw ideas that already exist from the void and bring them forth to show our belief systems.

I think the Biennale of Sydney was an incredible platform to show our Māori world view, and I was supported to scale up and really push the boundaries of what I thought was possible. And that's what the Biennale of Sydney and Foundation Cartier really facilitated. They recognised that it's really important at the moment to bring Indigenous artists to the forefront because our perspective is so important, especially now.

AK: So beautifully expressed. Is this the most significant work you've made to date?

NH: Yeah, it is the most ambitious work. It was really challenging.

AK: Can you describe a little bit how you make the bark cloth?

NH: It is made from the aute plant, and you take off the bast or the bark and you peel the outer bark and then you get this sappy bast and you beat that and scrape it and clean it and you kind of cleanse it of all of the sap inside of it.

The beating process expands it into cloth. We use this cloth for kākahu, adornment, clothing, wrapping precious taonga, or wrapping those who have passed away. So, it has a lot of transitional significance to our people.

It is very labour intensive, and the planning element for each of my projects has to happen way in advance because you have to cater to the season, the harvesting, soaking, and beating of the bark, as well as harvesting all of our pigments. I use ochre, red ochre and ngārahu, which is soot ink, and they all take time to prepare.

Aumoana>, the installation at White Bay, actually involves four other island nations: Ebony Fifita from Tonga; Kesaia Biowanua from Fiji; Hina Kunobo from Hawai'i; and Hina Teakolombani from Tahiti; and my apprentice, Rongomai Gerber-Coskins.

We each made different pieces to create this installation together, which is Aumoana, representing our ability to have radical hope for the collectivisation of our island nations. Oceania, the Moana Nui Akiwa, makes up one-third of the world's surface area. Before colonisation, there was much more of a relationship between all of us. It's a huge, vast, expansive space that we could navigate and travel between islands.

We had highly developed technology, which enabled us to do that and have those relationships with other islands. Now, there are borders, we're colonised by different people, and there are language barriers between us. My hope was to bring makers with a shared genealogical connection to this bark cloth together so that we had the opportunity to experience joy, work together, exchange knowledge, and facilitate a cultural exchange that will have long-lasting impacts within our communities.

AK: It sounds remarkable.> It's so ambitious in terms of the scale you're working on, bringing all these different artists together. It is extraordinary, really. It feels like a very generous project where you're all sharing things.

NH: Yes, the project's foundation was to extend this opportunity beyond myself and Te Ao Māori and foster relationships with other cloth makers. >Also, I'm very conscious of bringing up apprentices and younger bark cloth makers within my practice.

AK:> How did you learn to make bark cloth?

NH: I was really fortunate to be taken under the wing of Verna Takashima, a kapa maker in Hawai’i.

I have pretty strong relationships with Hawaiian cloth makers. I must acknowledge the revitalisation or reinvigoration of the Hawaiian kapa practice as a foundation for my learning. Because of it, when I came back to Aotearoa, I had kind of the tools and basic knowledge to investigate our plants and to find processes that were in alignment with the stories and the research on Māori Aotea in Aotearoa.

We have a framework within Māoridom, which is called tūakana teina. The tūakana is the older sibling and the teina is the younger sibling. It’s a fundamental foundational idea within our culture. It's also definitely played out within Aomoana because different cloth makers are at various stages of their cloth making journey. And then there's Fiji with an unbroken lineage of cloth making. They have never stopped making cloth, they have a solid foundation of knowledge and processes and technology that they've retained. Also, it's still massively used within their ceremony and their everyday. It's the same in Tonga.

So, there were a lot of different tūakana teina relationships within the group. But overall, we were held by a Māori value system that enabled us to come together and wānanga. It's wonderful.

AK: I imagine there are so many stages. I want to see your hands!

NH: Oh no, my nails. I just harvested this weekend. But because it's gotten a bit cold, we're at the season's closing, so it was tough.

AK: So, what's next for you, based on this beautiful collaboration you did for the Biennale?

NH: I think it was such a massive outpouring of energy, resources, and modi that what I really want to do now during this winter is sit in Wānanga and be a student again, visit my teachers, and re-establish the foundation of my practice—kind of come back down, really.

I'm still recovering from the whole process.

AK: I often talk with artists about how art is a process, right? The finished product is not the art; it's the product. The process is the art, and what you're describing is precisely that, right?

NH: Yeah, it's like a dance. It's a choreography, and it's a negotiation between the makers, but also between the plants and a negotiation of the plants' pigments.

AK: That’s beautiful. To finish, could you tell us why birds appear in your work? I'm working on a project about migratory birds with some First Nations artists.

NH: So, in Oana, I made these Manu Aute, which have lived in our consciousness for a very long time, even though the practice of Aute has declined in Aotearoa.

Manu Aute exists as an abstract, vague idea in our stories, constellations, and illustrations. But since the beginning of my practice with Aute, ten years ago, I've wanted to create these Manu Aute and materialise these forms that have existed in our consciousness for a long time.

Manu, their bird kites, have divination qualities. Our kites can have a potent impact on the result of war or dividing lands between siblings.

Also, White Bay is like this industrial void, and Aute represents everything that is the opposite. These Manu are flying in the air, and they lift up all of the other works to hang suspended in the space. Usually, you would never see cloths like this hanging in mid-air, so Manu can serve as conceptual beings that justify this work in this space and context.

All these pieces are trying to reclaim some of the technologies, processes, and knowledge systems that have maybe been sleeping or resting and attempting to achieve the fineness, flexibility, or softness of the ancestor cloths.