Dominique White ‘Deadweight’: Max Mara Art Prize for Women

“The sea is also a site for impossibility, a flattening of time and a rejection of order,” says Max Mara Art Prize for Women winner Dominique White, whose sculptural installation Deadweight is now on view at Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia.

Image credit: Dominique White, split obliteration, 2024, driftwood, high volatile charcoal, forged iron, metal wire, sisal, raffia, destroyed sails, exhausted ropes, Installation view, Dominique White: Deadweight, Max Mara Art Prize for Women (2022-24), 2 July - 15 September 2024, Whitechapel Gallery, London. Courtesy and © Above Ground Studio (Matt Greenwood)

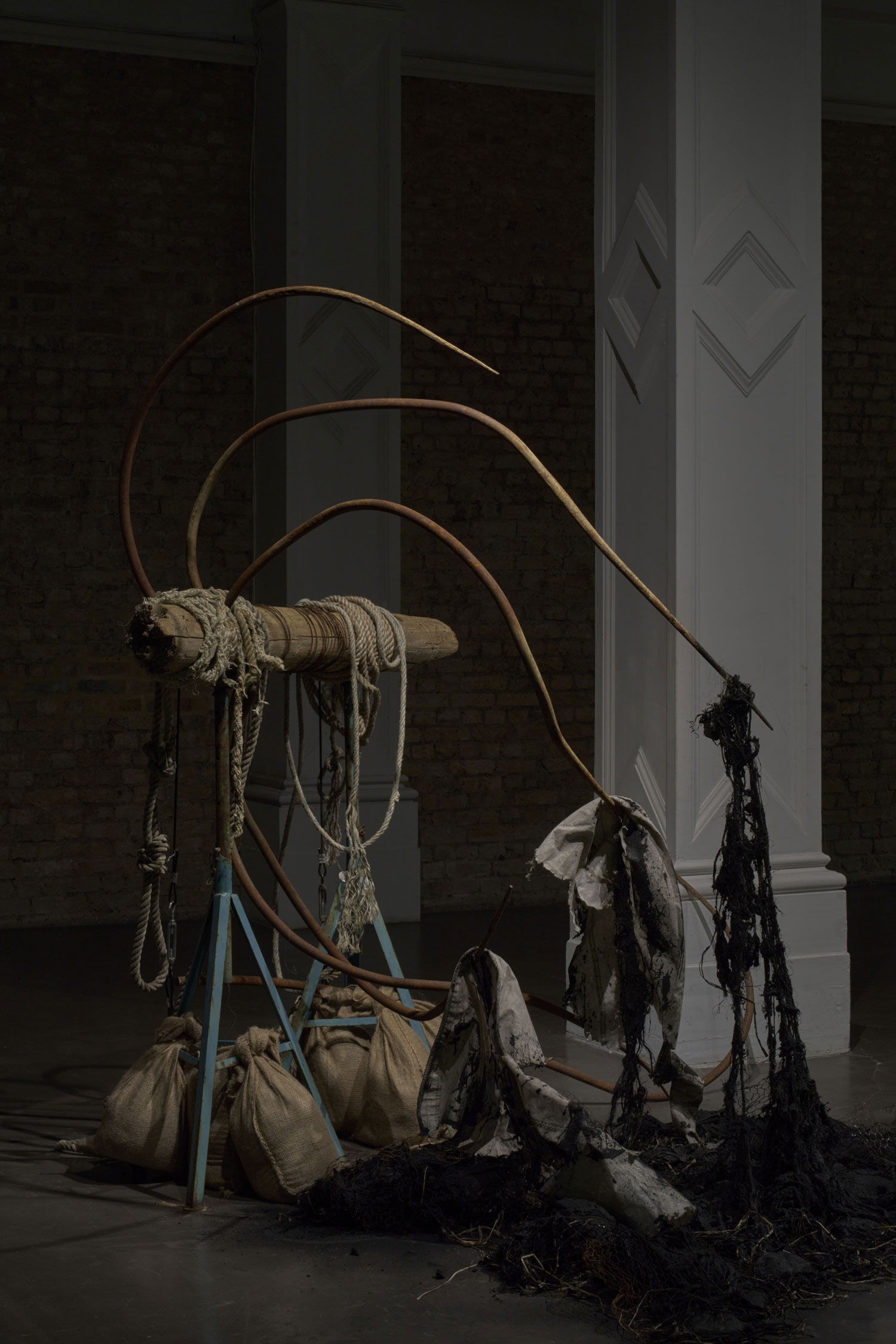

Sometimes, they look like ancient ship anchors on the verge of disintegration; other times, they resemble carcasses of giant prehistoric sea mammals bolstered to the seafloor. Deadweight– the sculptural installation by artist Dominique White–is inspired by her residency as the ninth winner of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women (2022-2024). Now on view at Collezione Maramotti, the exhibition space and contemporary art collection at the fashion house’s headquarters in Reggio Emilia, Deadweight is the culmination of White’s exploration into maritime and nautical themes and histories through the lens of Black Subjectivity. The work expresses the breadth of the artist’s research and conceptual explorations enriched by her residency across Italy as part of the biennial Prize, which is a long-standing initiative between Max Mara, Whitechapel Gallery (London) and Collezione Maramotti.

Image credit: Dominique White in her studio in Todi, 2024. Photo: Zouhair Bellahmar

“Deadweight (tonnage) is a unit used to measure how much weight a ship can carry. It is the sum of the weights of cargo, fuel, fresh water, ballast water, provisions, passengers and crew. Instead of using it to ensure the ship stays afloat and moves seamlessly, I want to use it to figure out its tipping point which is the possibility to sink it, destroy it, and free its cargo in the process,” says the artist.

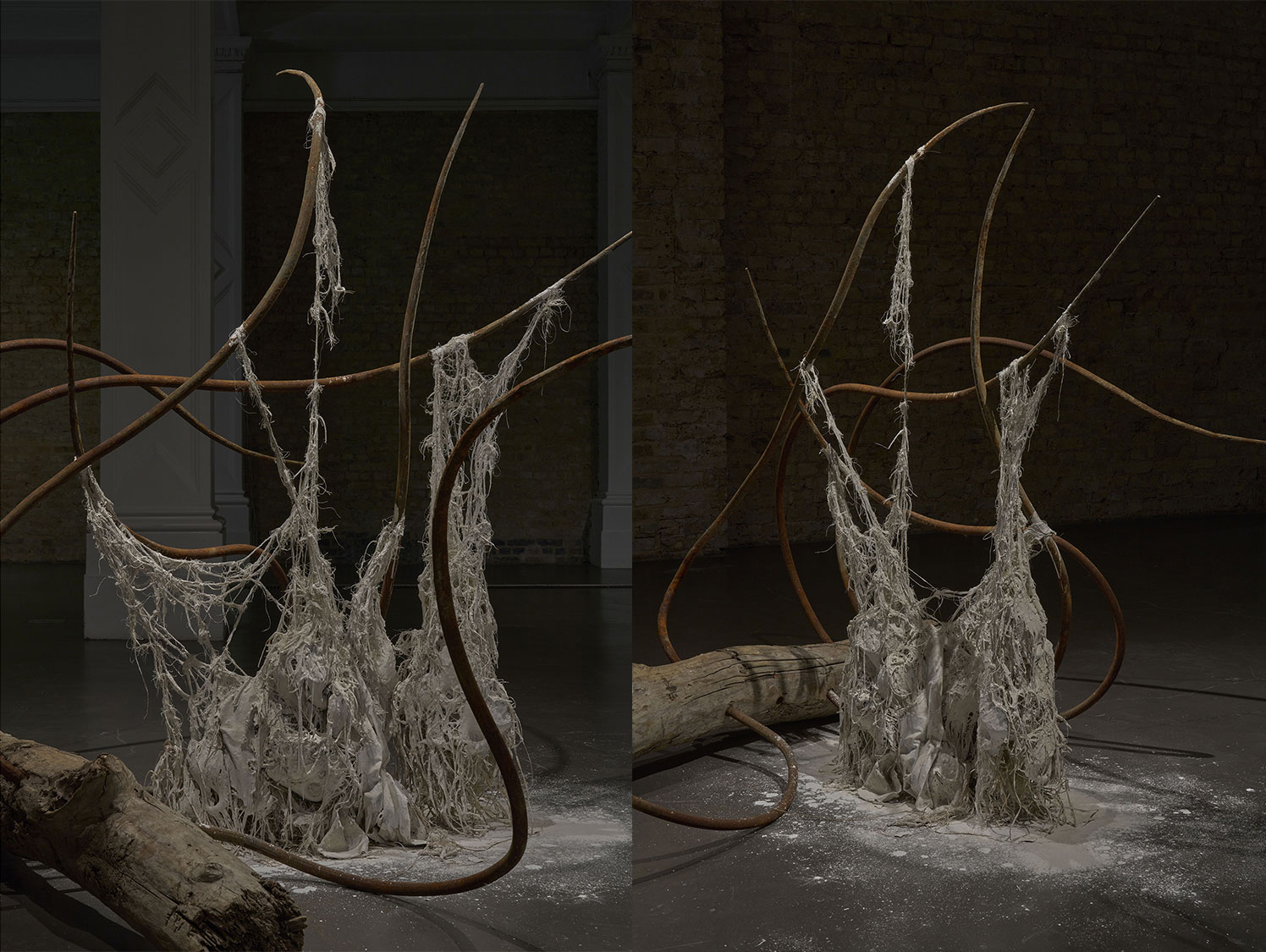

Mass and ephemerality, preservation and decay, disruption and liberation. Deadweight interrogates centuries-old maritime traditions and terminology, particularly their loaded histories of slavery and oppression. White’s four sculptures are, in her words, “hope” for an “alternative [Black] future that must be born from the ashes of the present.” Stark and angular in form, they have been created from maritime relics, including sails, masts, wood and rope that appear to have weathered their share of storms. The works also feature clay, driftwood and untreated iron, a material which, for the artist, signifies the presence of ‘Blackness’ and slavery in a historical maritime context. Deadweight’s materiality is inherent in the aesthetic and conceptual narrative, made all the more visceral by the sculptures’ evocative titles such as Ineligible for Death (2024, driftwood and forged iron) and The Swelling Enemy (2024, driftwood, forged iron, raffia, kaolin clay, destroyed sails). Ghostly yet immovable, impenetrable yet fragile, the sculptures were even submerged in the Mediterranean Sea as part of White’s artistic experimentation, an act that further charged their thematic potency.

Image credit: Dominique White, ineligible for Death, 2024, driftwood, forged iron, Installation view, Dominique White: Deadweight, Max Mara Art Prize for Women (2022-24), 2 July - 15 September 2024, Whitechapel Gallery, London. Courtesy and © Above Ground Studio (Matt Greenwood)

“I’m very interested in this idea of disrupting the power dynamic between object and viewer. I think when it comes to object making we’re taught to keep the viewer and the audience in mind– in the sense that the viewer will always have the power. For me, the tension between the actual heaviness of the work, the materials and the process of creating them, and their seemingly fragile appearance is where the disruption of power happens. It’s almost like a self-defence mechanism in the work –if you get too close, it might either destroy itself or harm the viewer. There’s a menace within the fragility,” White explains. Through this tension between fragility and harshness, the artistinverts historical ideas about a ship’s cargo, or as she describes it: “The idea is that those deemed as cargo or having limited value within a ship–pirates, runaway slaves, slaves and others–can overthrow the hierarchy on board and therefore destroy order on land.” The sea, therefore, is a site of transformative power for the artist, capable of rejecting order and levelling the current of time physically and conceptually.

Founded in 2005 by Whitechapel Gallery in collaboration with Max Mara, the Max Mara Art Prize for Women offers female or female-identifying artists the opportunity to undertake a bespoke residency tailored to their research objectives. Engaging with both maritime history and traditional artisanal practices, White’s residency commenced in Agnone (Molise), where she explored the nuances and limitations of working with bronze during a workshop at the historic family-run Pontificia Fonderia di Campane Marinelli, where some of Italy’s oldest and most storied bells have been produced for over one thousand years. She then explored ship navigation technology and colonialism in Palermo (Sicily), engaging with renowned historian Giovanna Fiume as part of her detailed research and development. This was followed by a series of naval and archaeological discoveries in Genova (Liguria)–historically one of the most important port cities in the Mediterranean–under the guidance of professors Claudia Tacchella and Massimo Corradi. A workshop at Milan's Fonderia Artistica Battaglia enabled White to experience the centuries-old tradition of crafting bronze artefacts by hand, while in the medieval town of Todi (Umbria), she honed her metalwork and fabrication skills with mentor Michele Ciribifera. It seems that Italy, with its abundance of historical, cultural and artistic inspiration spanning the regions, enriched White's preferred research method based on amassing a ‘library’ of references, including theory and history, poetry, music and found objects which inform her sketches, preliminary studies and decisions on materials and forms for her artwork.

Image credit: Dominique White, the swelling enemy, 2024, driftwood, forged iron, sisal, raffia, kaolin clay, destroyed sails, Installation view, Dominique White: Deadweight, Max Mara Art Prize for Women (2022-24), 2 July - 15 September 2024, Whitechapel Gallery, London. Courtesy and © Above Ground Studio (Matt Greenwood)

“One of the main criteria of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women is that the winning artist has not yet had a major solo survey exhibition. As a result, the Prize nurtures emerging artists by giving them time and resources to develop ambitious new work and valuable exposure through exhibition opportunities. Previous winners reflect that it’s a life-changing experience, and most of them go on to have great recognition in their artistic careers following the Prize,” says Sara Piccinini, Director of Collezione Maramotti.

Located in Max Mara’s headquarters on the outskirts of Reggio Emilia, Collezione Maramotti is the permanent site of a contemporary art collection initiated by the fashion house’s founder, Achille Maramotti, in the 1970s. Reflecting the founder and collector’s vision to nurture the most pioneering and progressive artistic innovations of his time, the Permanent Collection consists of several hundred works by artists including Lucio Fontana, Alighiero Boetti, Francis Bacon, Alex Katz and Chantal Joffe. This spirit of innovation, experimentation and discovery continues today through initiatives like the Max Mara Art Prize for Women, which, in Dominique White’s case, has nurtured the creation of her most ambitious sculptural work yet:

“The forms of these works are something I’ve never created before, which both excites me and scares me - for good reasons. It’s good to be scared.”

Deadweight is now on view at Collezione Maramotti until 16 February, 2025.