Jenny Holzer: Sign of the Times

American artist Jenny Holzer’s practice explores the power of language as mediated by technology. VAULT looks at Holzer’s new exhibition, which engages with the current state of American politics – and employs AI to do so.

Image credit: Jenny Holzer, Ready For You When You Are, Installation view, Hauser & Wirth, West Hollywood, 2023. Photo: Collin LaFleche. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Jenny Holzer All rights reserved, DACS, London / ARS, New York 2023

“For an artist as interested in language and power as Holzer, it is perhaps unsurprising that this development coincides with the recent explosion of generative text AI applications available to the general public, including but not limited to the infamous ChatGPT”.

At the beginning of September 2023, READY FOR YOU WHEN YOU ARE, a major new solo exhibition by Jenny Holzer, opened at Hauser & Wirth’s new West Hollywood space in Los Angeles. Across precious metals and oil on linen, distressed metals, stone, and robotic LEDs, Holzer’s juxtapositions – fact and fiction, real and synthetic, digital and analogue, public and private, permanent and temporary – explore our recent past, present and possible future. The exhibition marks a pivotal moment in the artist’s practice.

Jenny Holzer’s name is synonymous with pithy texts – from her Truisms series (1977–79) across the streets of New York, to her public light projections shown in major cities across the globe. For five decades, across public and gallery spaces, Holzer has interrogated the form, function and power of language, asking audiences to consider what they see, think, read, write, hear and say. In READY FOR YOU WHEN YOU ARE, for the first time, Holzer features synthetic texts, representing her first forays into AI, alongside borrowed texts such as public tweets and declassified government documents. For an artist as interested in language and power as Holzer, it is perhaps unsurprising that this development coincides with the recent explosion of generative text AI applications available to the general public, including but not limited to the infamous ChatGPT.

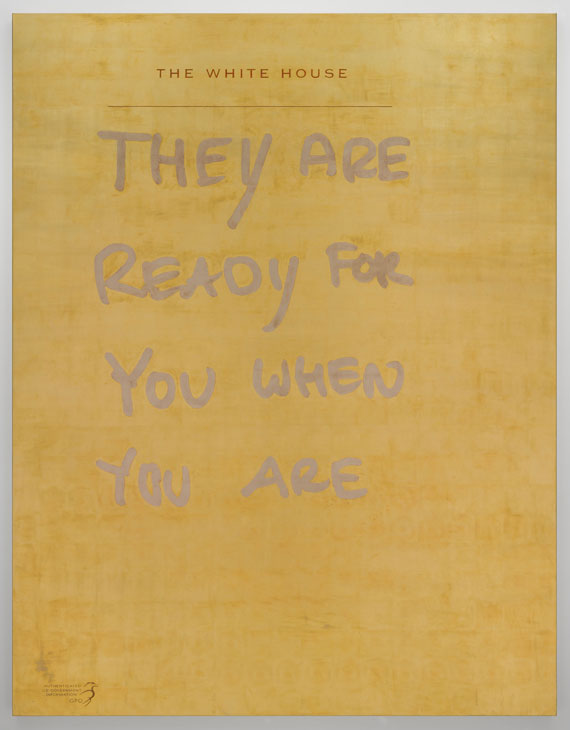

The exhibition takes its title not from these ‘new’ synthetic texts, but from the ‘borrowed’ text of one of its paintings. READY FOR YOU (2023) is a large-scale version in gold leaf and oil of a handwritten note passed by an aide to then-U.S. President Donald Trump on January 6, 2021 – the day of the attack on the United States Capitol by a mob of some ten thousand Trump supporters. Written on a White House pocket card, the note – and Holzer’s painting – reads: “THEY ARE READY FOR YOU WHEN YOU ARE” (sic). Shortly after receiving this note, Trump delivered a speech from the Ellipse in Washington D.C. In that speech, he encouraged his supporters to march on the United States Capitol, as Congress certified the results of the 2020 presidential election in favour of President Joe Biden. The original note was preserved by the National Archives and Records Administration, submitted to the United States House of Representatives’ committee investigating the attack, and cited in its final 2022 report.

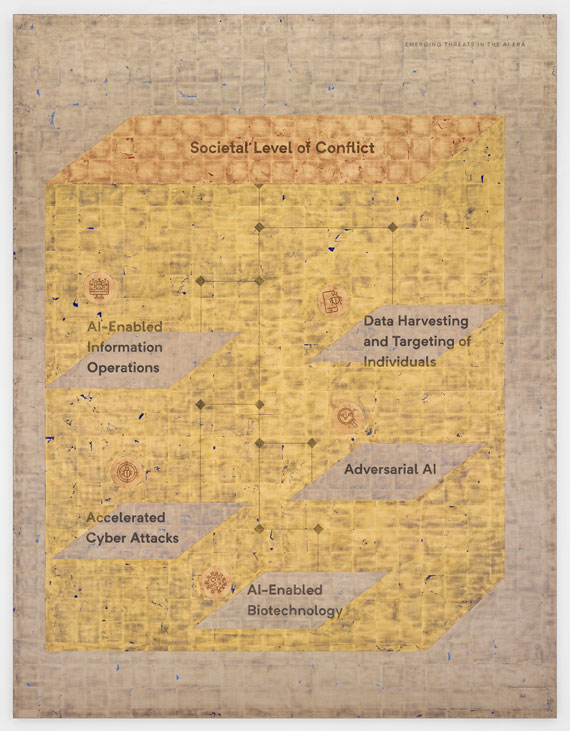

READY FOR YOU is one of 13 iridescent large-scale paintings in precious metals and oil on linen lining the exhibition’s walls, with a 14th presented on the floor. Most of these paintings belong to Holzer’s ongoing Redaction Paintings series. Since 2005, Holzer has been producing these paintings using her extensive research into declassified U.S. government documents – including FBI reports, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and National Security Archive (NSA) documents, and government memos – often released through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests and sourced by the artist through the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), NSA websites, and government agency websites. The titles of these paintings are drawn from their few surviving lines of text. SOFTER TARGETS (2023), for example, is a recreation of a page from a 2004 FBI counterterrorism report, assessing international and domestic threats including Al-Qaeda, right-wing extremists, white supremacists, animal rights groups, eco-terrorists, anti-abortion extremists and hacktivists. The text is entirely redacted except for the subheading “Shifting to Softer Targets”. In her Redaction Paintings, Holzer casts light on the machinations of military and intelligence bureaucracies in the shadows of our everyday lives.

The unearthed texts from declassified documents in these paintings are juxtaposed with works using public tweets by Donald Trump and online posts by Q, the anonymous leader of the far-right QAnon conspiracy movement. Q – whose posts reference government corruption, media brainwashing and revolution – claimed to be a high-level government official with access to classified information in the Trump administration. The QAnon movement spread misinformation in favour of Trump’s 2020 re-election bid, which was amplified by Trump via his social media platforms. QAnon was classified as a domestic terrorist threat by the FBI in 2019, on the grounds of having incited violent incidents.

Tweets by Trump and posts by Q are continuing subjects and sources for Holzer. Putin and I Discussed (2022), for example – produced by the artist on the occasion of the major Ever Goya (2021–22) exhibition at Fondation Beyeler – uses selected tweets by Trump from his presidential term. One of the 11 tweets in the editioned work on Hahnemüle photo rag reads: “… if Turkey does anything that I, in my great and unmatched wisdom, consider to be off limits, I will totally destroy and obliterate the Economy of Turkey (I’ve done before!)” (sic). Extracting these texts from their original setting on our screens and newsfeeds, Holzer emphasises the ways in which we regularly dismiss and discard their messages, their power and their consequences. Holzer asks audiences to remember that this is real life.

In READY FOR YOU WHEN YOU ARE, Holzer takes this even further, presenting selected tweets by Trump as CURSED (2022) – 296 ‘curse tablets’. These are contemporary versions of Ancient Greek and Roman defixiones (κατάδεσμος/katadesmos, from the Greek and Latin words for ‘bind’ and ‘pierce’). Some 1600 of these artefacts have been discovered across Europe, inscribed in Greek and Latin by ‘curse writers’ on metal, stone and ceramic tablets. They are petitions for divine intervention, typically to gods of the underworld (Hades, Hecate, Persephone and others), asking for the exaction of vengeance or the return of stolen property. Their use of quasi-legal phraseology endows them with a particular authority; consequentially, some academics describe them as ‘judicial prayers’. Usually, after being rolled, folded or pierced with nails, these tablets were placed underground – in graves, in subterranean temples and in bodies of water.

Holzer’s curse tablets, however, are meant to be seen. Taking texts intended for public consumption and presenting them in the tradition of curse tablets and in the mode of artefacts, Holzer asks whether these will become the relics of our time. In lead, copper, brass and nickel-silver stamped with text, ‘aged’ and distressed through various physical and chemical processes, Holzer’s curse tablets are scattered in a diagonal line stretching across the gallery’s polished concrete floor before ascending the wall like climbing, corroded ivy. Their subjects include Trump’s personal life, pop culture, international and domestic politics, criticism of the media, impeachment and alleged election fraud. “Fake President!” concludes a 2020 tweet carved into one weathered tablet.

Despite the hyperbolic and divisive nature of the texts used in CURSED, and in Holzer’s paintings, these works ground the exhibition. Their perhaps unexpected stillness functions as a counterpoint to the robotic LEDs, and the AI presented alongside and above them. Suspended from the rafters directly above CURSED, for example, is WTF (2022), a kinetic sculptural work affixed to heavy steel tracks with a system of pulleys and cables. A chaotic, digital battering ram, WTF is a four-sided LED beam emblazoned with all-caps texts drawn from tweets by Trump and posts by Q. These texts scroll across the four narrow LED panels changing direction, fading in and out, colours switching and pixels glitching, as the beam swings and jerks in unpredictable fits and starts up, down, back and forth across the gallery. Holzer’s intention is for the beam’s erratic movements to mirror the manner in which these messages from Trump and Q were shared online.

Despite the energetic spectacle of WTF, neither it nor CURSED nor the 14 metallic paintings that set the exhibition’s tone are its focus. READY FOR YOU WHEN YOU ARE instead centres on GOOD (2023) and BAD (2023), a pair of kinetic LED works created using robotics and AI. Holzer has been experimenting with different types of hardware and software in her practice since 1982, when she presented Truisms on electronic signs in New York’s Times Square. Since the 1990s, she has worked with multi-sided LEDs – such as those in WTF, GOOD and BAD – and in projection mapping. Since 2015 she has also experimented with robotics, and in more recent years with augmented reality (AR) – such as with Like Beauty in Flames (2021), a dedicated AR application for the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

GOOD and BAD mark an inflection point in Holzer’s practice, and in her five decades of explorations with ‘original’ and ‘borrowed’ texts. While Holzer largely retired from producing language herself some time ago, and in recent years has sourced texts from poets, authors, leaders and public figures, GOOD and BAD are her first works using AI-generated texts. GOOD and BAD were created using large language models (LLMs), a type of generative AI to which ChatGPT, for example, belongs. Such pieces of software (computer programs) are ‘trained’ on millions of pieces of text data, which are processed using what is termed a ‘neural network’. These programs are then prompted to create new texts based on their ‘learning’. Where LLMs sit on the spectrum of automation to AI (simple robotics belonging to the former) is a subject of debate. In essence, they provide, based on their large-scale statistical analysis of the texts on which they are trained, to generate new sequences of words.

For GOOD, the AI text generators used by Holzer were prompted to create texts about human, nonhuman, physical and immaterial ‘good’ things. The resulting texts describe love, dreams, visions, inspiration, light, nature, utopian communities, immortality, extra-terrestrials and more. For BAD, the AI text generators were prompted to create statements and poems in the rhetorical style of alt-right and far-right groups, using excerpts of extremist content for reference. The resulting texts describe disinformation from mainstream media, political correctness, the threat of socialism, the deception of climate science, the danger of federal regulation, fraudulent elections, corrupt leaders, secret cabals, insurrection, invasion and a coming doomsday or civil war.

GOOD and BAD are each composed of a vertical four-sided LED beam, suspended from the ceiling and rotating – in an unpredictable pattern, clockwise and counter clockwise – on a robotic axis. In shades of black, white, red, violet and fuchsia, their AI-generated texts glide up and down each side of the LED beams. The vertical, angled, circular motion of the LED beams hints at incantation, while letters and words appear to rise from the floor, evaporate into the air, and materialise through crackling static. An excerpt from BAD reads: “The cloud of fear is over us. Alarm – suspicions grow. Do you believe in corrupt power? Do you fear a secret cabal? Trust us – we are in charge. Patriots. Wake up sheeple. The deep state tyrants are here. They will try to manipulate and take away our rights. We must stand united against this evil. We must fight back. We must defend our freedoms!” Flashes of red, violet and fuchsia from the LED beams are reflected on the smooth concrete floor, bouncing off and onto the gallery walls and dancing across the mottled texture of nearby paintings. The effect is a digital sort of mystical or magical space.

We find ourselves, in 2023, at a turning point for art-and-AI – marked most decisively, perhaps, by Jerry Saltz’s recent review of Refik Anadol’s exhibition at MoMA, which he described as a “narcoleptic soup”. Mainstream awareness and understanding of AI, and especially of generative AI, is at an all-time high. Much of the initial novelty and stupefied awe engendered by AI’s applications across creative pursuits has worn off, giving way to more sober reflection and criticism. A computer creates an image or a text and, instead of unfettered applause, we now ask: so what? How does this ‘new’ image or text transcend its source material? What does this ‘new’ work mean? Does it mean anything at all?

The substance and significance of the ‘creative’ output of generative AI systems depends on the type of system and data in question (how and by whom it was built, how it operates, whose data has been used to train it, and how). It is essential, as art-and-AI continues and evolves, that artists and creative practitioners share, publicly and in some detail, the methodology behind their AI works – not only because it provides essential context for interpretation and critical evaluation, but also in the interest of rights and attribution for any and all collaborators. Holzer might have provided more details here for GOOD and BAD.

Language is a specific and limited form of knowledge representation – a set of shared symbols used for communication, connection and meaning. We view language as limited because we understand it to be an extension of thought, and of the wild and nebulous landscape of cognition. To move from cognition and thought to language requires intention. What, then, do we make of language ‘created’ by a computer, an entity without verifiable intention, thought or cognition – at least as within our current, anthropological definitions.

In the case of Holzer’s GOOD and BAD, the AI-generated language might be seen as not language at all, but as abstractions of language. There are no pretensions of consciousness for the AI text generators Holzer has used; their lack of originality or authorship is, in fact, the point. Holzer has utilised these tools not to create new texts and marvel at the ostensible sentience of a machine, but to create statistical imitations of the language of our day – the things we see, think, read, write, hear and say – and reflect it back to us. Juxtaposed with ‘borrowed’ texts, these ‘new’ synthetic texts, and their artworks, are simply a continuation and evolution of what Holzer does best: a sign of the times.

Jenny Holzer is represented by Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles and Sprüth Magers, Berlin and London.

hauserwirth.com

spruethmagers.com

projects.jennyholzer.com

Image credit: Jenny Holzer, Ready For You, 2023, 24k gold and moon gold leaf and oil on linen, 203.2 x 157.5 x 3.8 cm. Photo: Sveva Costa Sanseverino. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Jenny Holzer, All rights reserved ARS, New York 2023

Image credit: Jenny Holzer, Ready For You When You Are, Installation view, Hauser & Wirth, West Hollywood, 2023. Photo: Collin LaFleche. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Jenny Holzer All rights reserved, DACS, London / ARS, New York 2023

Image credit: Jenny Holzer, Accelerated, 2023, 24k gold, moon gold and red gold leaf and oil on linen, 259.7 x 200.7 x 3.8 cm. Photo: Sveva Costa Sanseverino. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Jenny Holzer, All rights reserved ARS, New York 2023

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 44 (November 2023 – January 2024).

Click here to Subscribe