Kiki Smith: Turning Over, and Over, and Over, and Over

This multidisciplinary artist combines material and formal experimentation with a self-described pragmatism, resulting in a career of unusual longevity and vitality.

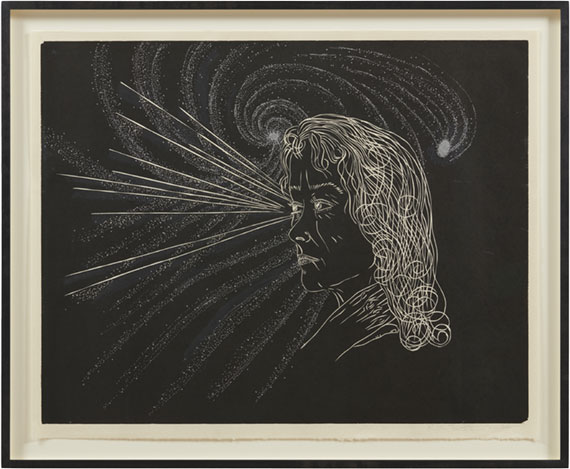

Image credit: Kiki Smith, Whirling 2, 2022, ink, acrylic paint on paper, 59.1 x 73.5 cm. Photo: Kyle Knodell

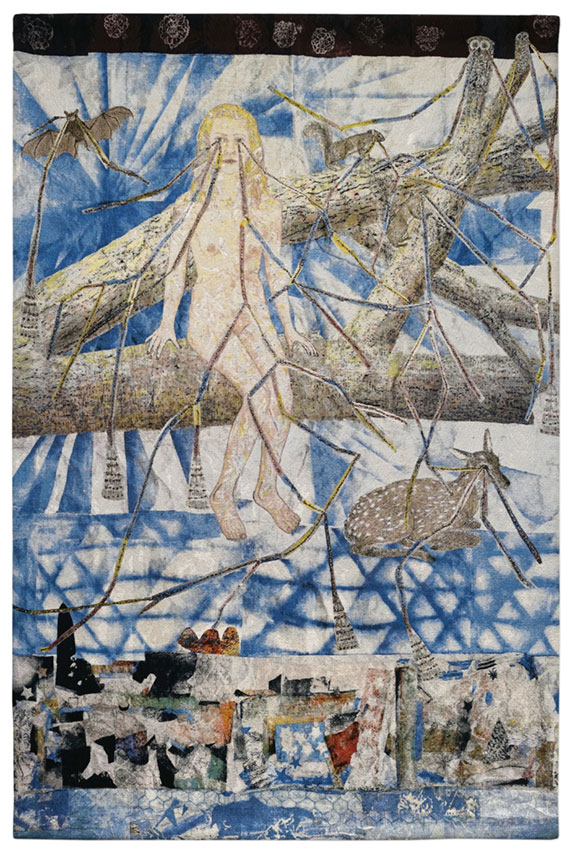

Kiki Smith has been exhibiting internationally for over thirty years, but only recently – as part of the 23rd Biennale of Sydney: rīvus – was a significant presentation of her work seen in Australia. Each of the five pieces shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art began as handmade collages, rendered over the course of a year-long collaborative process into largescale tapestries that echo their medieval forebears.

With a characteristic style that draws on mythology, fairytales and religious iconography, Smith often incorporates the human body as a form that unites us with one another, while also highlighting our interconnectedness with non-human players: birds, wolves, wild forests and starlit skies feature prominently. Though often large in scale, her works retain an intimacy and delicacy of touch, which perhaps can be tied to the central role that printmaking has played since her involvement in the New York artist group Colab in the late 1970s.

I spoke to the artist from her home state of New Jersey – where she grew up in the company of well-known minimalist and abstract artists of the 1950s and ’60s, among them her father Tony Smith – about her latest commission for the city of New York, her ongoing passion for printmaking, and the spiritual challenge of cleaning the house.

Thinking about the creatures – human and more-than-human – that have populated your work for decades now, it’s interesting to note that your lived experience of making work really started with abstraction.

Well, making work out of lumpen materials is completely abstract. If you’re printmaking, it’s just a piece of paper and ink; there’s nothing inherent in it that has to do with an image. It’s a complete illusion of an image. Making a representational image for me is a pleasure because I didn’t grow up with it. Representation was something stranger to me than abstraction.

For me, representation is an easy hook – it gives me a form to work around, a focal point. You can have all these secret things that you’re trying to do within the guise of making a picture of a bird. But at a certain point, the work takes the lead. You try to keep up with it, change with it, go where it wants to go.

And where does it want to go now?

I’m very interested in printmaking and learning different aspects of it. Even though I’ve been making prints for twenty or thirty years, I’ve remained within a very narrow range. But it’s such an infinite space and I’m using it over and over and over again. I would say that 80 to 90% [of my works] come directly out of prints that I’ve made – reconfiguring those prints, making them into sculpture, tapestry. That’s what I really enjoy the most – making images, or making patterns, and having them transmutate into something else and something else and something else and change scale, change dimension, change material.

I just made these big mosaics for the city of New York [in the new Grand Central Madison Station], working with mosaicists in Munich. There’d been 30 people working on them over two years. The mosaics are rehashes of everything else I’ve ever done in my life. I really love that now I have years of these images turning over and turning over and turning over and turning over – showing facets of them, giving them different lives. A great deal of the images I work with I made in 1994.

What was happening in 1994?

I did a residency at Alfred University and then a residency at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt). At Alfred, the janitor had a collection of dead birds and I made etchings from them that I’ve used a lot in my work. And at MassArt I went to Harvard, to the Peabody Museum, and they had all these stuffed animals – I could go there and draw them and they didn’t move. I made etchings and photo-lithography from them. I wanted to draw all the animals in the bible but then I started thinking about whales and I like making things one-to-one and I didn’t have the energy. Those are the images that I keep using, and I’ve added more to the vocabulary.

I never had any particular aptitude for doing things. I knew people who could really draw very well, but it didn’t mean anything to them. I see that with lots of able to render things, but they don’t need it. For me, I really like being in a struggle with something, not being good at something but struggling until I can make it my own. Your deficits are where you find energy inside of you. The couple of times when I thought I was sort of getting good at something it totally bored me to death.

So, when you look at your finished work are you still thinking about how you could improve it or what you could have done differently?

I used to wish lots of things I made would spontaneously combust. But you get to a point where somehow it satisfies you. It’s a temporary satisfaction. Art is inherently unsatisfying; you have to keep gnawing away at it.

Making calms my brain down. It’s a way to be present. When I was younger I had to be doing something with my hands all the time or I’d go crazy. It was excruciating just to sit. There’re physical activities you can be doing which are acceptable to do around other people, like knitting, but working on sculptures wasn’t always what people thought was okay.

Your work is often framed in relation to spirituality and mysticism. I’m wondering if you think about it in this way?

I think that it’s certainly good to be in body, mind and spirit – whatever that means. I’m not sure that I contain all of those things at any given moment. Our idea of those things comes and goes in life. My spiritual endeavour today is just to keep a clean house.

That’s a Sisyphean task.

If I could be a good housewife I would be very content in life. But I fight it. Today I cleaned the house and I thought, this would go by so much faster if I would stop fighting and resenting having to take care of myself. But I don’t feel like that with work, I don’t resent it or feel like it’s in my way. So I think that our spiritual challenges are very mundane and very abstract at the same time. And sometimes not very much connected to daily life and sometimes endlessly connected to daily life. Spirituality has many different guises.

Let’s jump from spirituality to feminism. Could you reflect on being a woman in the arts over the span of your career?

I’m 68 years old. The previous generation [of women artists] were present in the art world when I came in, and that gave me a sense of possibility for myself. I feel super lucky because there was really a strong interjection of women in the generation before me, who are now in their 80s or 90s. Those women fought a great deal for inclusion and had, in general, very marginal inclusion. And now I see a younger generation feeling entitled to be artists. I feel very privileged that I got to be an artist and that for half of my life I’ve supported myself as an artist.

There’s still not economic or representational equity, and there certainly wasn’t a variation of cultural representation when I started out, but all these things have changed and continue to change to make a more equitable, open society, where people can go about doing what they want. And some artists will be paid attention to not based on the particulars of who they are but on how their work functions.

I know great artists whose work was just not seen. Sometimes, with women, they are exhibited towards the end of their lives because the art world realises there’s a big cache of work that’s been sitting around.

A ‘discovery’ ...

Exactly. But I know men and women whose work has not made sense at all. Something had to change in society and all of a sudden it opened a window or enabled a language for seeing their work that wasn’t there before. We’re not on our own time. That has to do with larger cultural things happening at any given moment. I made things at a given moment that sort of fit with what people were thinking about. I think if I had come in with what I make now it would have seemed very odd.

Is there a particular work or series that you’re thinking about?

Well, I made things about bodies because bodies were something that people were very actively thinking about. The body, the autonomy, the integrity of the person in relation to society. Even now, the last several years with these pandemics have brought all of these issues very much to the forefront again – trying to figure out what the individual and the whole mean in relation to each other, how to exist together.

In the late ’70s and ’80s, I was young and had to think about what those things meant to me. I had to live through myself, the uneasiness and awkwardness of myself. At the same time, there was a tremendous pressure from the world to try and fit into some version of myself that I didn’t identify with, or didn’t want to. It just fit with the times, because people were very directly talking about bodies and I was sitting at home fabricating them.

It strikes me that one of the great strengths of your work is that while very personal it is not autobiographical, it operates via symbolism.

I don’t want to speak about myself personally at all. I mean, it’s personal. I’m doing things because I want to make my life better but I don’t want it to be autobiographical, even when I use my own image.

This guy [Donald] Winnicott, a psychoanalyst, had some nice sentence that was about artists revealing themselves and remaining hidden. I always liked that. I like that you get to put yourself out there in the absolute most personal way you could possibly imagine and at the same time there’s a space between you and the audience. There’s something that represents you in the world but it also protects you from the world. I’m not interested in people knowing anything about me particularly, because I’m just concerned with cleaning the house. I’m totally interested in endlessly mundane things, like how not to kill plants.

I’m such a pragmatic person. If you want to be an artist, I think it really helps to have a pragmatic side because you have to get things done. You can’t just talk about it, you have to manifest it and live through the uncertainty of having a relationship with inanimate objects.

Where does that pragmatism come from? Was it learned?

Certainly from my father. He was an architect before he was artist. Architects can draw something on a piece of paper and it can become a city, or a building. They can make that leap of faith. And I saw it happen. My father would make a little doodle on a piece of paper, then he would have us make models for him and then he’d call up the foundry and send them drawings and we would go see it. So I saw this process, that it was possible to make something.

The thing I always like, that I think is revolutionary about artists, is that it’s self-proclaimed. You take it. You say: “I need this, I want this, this is what I’m willing to put my energy into.” And it’s certainly an unknown space to go into. I’ve been endlessly fortunate in it since I was 34 years old. That’s highly unusual for 99% of artists. And I’ve had times when I’ve said I don’t want to be an artist anymore, or when I thought it was all going to end, to dry up, that I’d never have another idea again.

Do you still think that?

Well, now I don’t care. But it doesn’t happen. You have to have faith in the process, that it’ll reveal itself on its own terms. It’s like a collaboration between you and the universe. And it goes in sometimes very uncomfortable ways. But if you follow it, it’s a lot better than trying to control it.

Your work can do a great deal in sustaining you if it sustains your interest – then you always have something to attend to. I think that’s very brave of people.

Are you in the studio every day?

I live and work in the same space. I do something everyday but it’s not always making. Sometimes it’s answering emails incessantly. Or making layouts with people. Sending packages to people. A lot of it is really boring. It’s like having a job. That’s where I say I’m pragmatic. I don’t like doing it but I see it’s in my interest to do it. It enables me to do things that I want to do.

Who are the artists that you pay attention to?

I like all artists. I grew up around artists. I practically only know people who are artists. Everyone’s so singularly on their own weird trip. I have great respect for many artists, just watching them sustain themselves. I really like art a lot. I like how it can go anywhere. There can be endless discovery. There’s nothing finite about it. People are always having personal discoveries and then larger cultural discoveries. It’s an infinite language. I can have my taste, but I think that’s the most limiting, the most corrupting part of oneself, that appreciation for one thing over another. Certain things that really annoy you at one point in your life, become completely fascinating at another point.

I think the best work resonates across multiple aspects and at multiple levels of consciousness when you engage with it.

Let’s talk a bit about what’s next for you. You’ve been practising for so long and experimented with so many different forms …

But I’m not practising. I’m just doing it. Practise can imply you’re getting somewhere. I’m not getting anywhere, I’m having a pure momentary experience. I used to like that [term], practising, because it’s like Buddhism sneaking in, but it has so infiltrated the art world.

Ha, that’s true. Okay so you’ve been doing it for decades – is there a particular material or technique that you have your eye on to work with?

I always want to make more stained glass without poisoning myself with lead. I’ve basically just used black on clear or milky glass, and I would really like to learn how to use colour. And to make another mosaic. And tapestry. And lots of prints still. I have to keep around for a little while longer. I’m not intentionally trying to do anything really, things just come and up and I think, “Okay, that’s possible.”

Kiki Smith’s Free Fall is at Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), Korea, until March 12, 2023.

sema.seoul.go.kr

Kiki Smith is represented by Pace Gallery, New York and Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston.

krakowwitkingallery.com

pacegallery.com

Image credit: Kiki Smith, Congregation, 2014, cotton Jacquard tapestry, hand-painting and gold leaf, 287 × 190.5 cm. Published by Magnolia Editions. Photo: Magnolia Editions

Image credit: Kiki Smith, Restless Drawing, 1994, collaged letterpress and lithograph on Nepalese paper, 119.4 x 227.3 cm. Courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo: Ellen Page Wilson

Image credit: Kiki Smith, Pilgrim, 2007-2010, leaded stained glass in steel frames 41 elements; installation dimensions variable. Photo: G.R. Christmas

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 41 (Feb – Apr).

Click here to Subscribe