Sarah Lucas: In Conversation With Dr Laini Burton

VAULT speaks to Sarah Lucas about sex, toilets and sculpture.

Image credit: Sarah Lucas, ALICE COOPER, 2020, tights, wire, wool, spring clamp, shoes, acrylic paint, metal chair, sculpture: 99 x 50 x 90 cm, plinth: 20.3 x 121.9 x 121.9 cm. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

Thank you for your time, Sarah. I imagine you are a busy woman, so I’m going to dive right in. Your use of humour has always been an effective way of circumventing or disarming bodily taboos. After so long exploring these moral and psychological dilemmas, what do you think is at the core of our discomfort with sex, genitalia, desire and bodies?

It’s a lot of things. Many of them very subtle, unspeakable and even unthinkable. Societies need taboos and conventions of behaviour. We’re born into a world that is not a blank page, and we have to learn the rules and get on with it as it is. Which we do, like learning to talk, unquestioningly, during our formative years. It’s a process of indoctrination from the outset.

Questions do occur to us along the way. We develop a sense, or learn through experience, which questions can be asked and which ones are better kept to ourselves. Swearing is a good example of this. We know what the bad words are before we know what they mean. And often, what they actually mean doesn’t seem as bad as we thought – unless they’re coming at you with aggression and venom behind them. Basically, we find ourselves in a situation of being judged all the time. It becomes an inner voice.

Think of the taboo around going to the toilet. Quite a perversion really. Building these little private rooms where we can be invisible, receptacles that carry our excreta far away from us and out of sight. Segregation in public places of men and women. All very unnatural. Only beasts are natural.

Insecurity. Women have more than their fair share of it. We’re vulnerable. Preyed upon. Unsafe on the streets, even in the home. Many women are juggling jobs, necessarily part time because they are also caring for children, elderly relatives and men. None of the things that confer great prestige.

The sexist, dominating language of our culture – including the constant television and film stories portraying women being raped and murdered – doesn’t help. Neither does continually being targeted by ads about how we can look better. Advertising is a major culprit. Insecurity shifts product. Constant self-consciousness.

Religion and taboos and expectations about what we should be exist to control and shame people. It is deeply ingrained humiliation on a complex and grand scale that we all dream of improving our way out of.

Thinking about the male gaze, do you feel it still weighs as heavy as it once did?

It’s still ubiquitous. Women are still sexualised everywhere you look. Make up, plastic surgery. In older women it’s about trying to hang on to some vestige of youthfulness. In younger women it seems the most popular procedures are lip fillers and breast augmentation. If you think about it at all, it’s clear that it’s about emphasising the sexual organs. Objectification. And it occupies a super important place in our culture. It may not only apply to women, but women are the model.

There have been significant shifts in gender and body politics since your sculptures took on their now-distinct polymorphous sexuality. Have you noticed these shifts affect the reception of your work?

Have there been significant shifts? Yes, there is more media coverage of nuances in sexual orientation. We hear a lot about it. But a lot of basic inequalities in gender and class still persist. Inequality of income is worse than ever. And that’s oppressive.

Leaving school at the age of 16, naturally I was dying to get out into the world. I hadn’t given any thought at all to what I’d do. I wanted money of course. I remember scanning the classifieds for a job and it hitting me just how badly paid and shit most of the jobs were, and so many required particular kinds of dress. I saw dreariness stretching ahead of me into infinity. Well, I think it’s a lot worse now and not going in a better direction. Shit money, no job security. The usual soul-destroying work benefitting the very few. Also, we are constantly being watched and monitored. Prison, in fact.

I find it impossible not to empathise with your Bunny sculptures. I am reminded of sex workers sitting behind glass walls as seen in red light districts – bored, world-weary, objectified, performing gender. However, they seem to have matured; some seem positively confident now – Elf Warrior (2018), for example. Does this echo your feelings about how the Bunnies and NUDS have evolved?

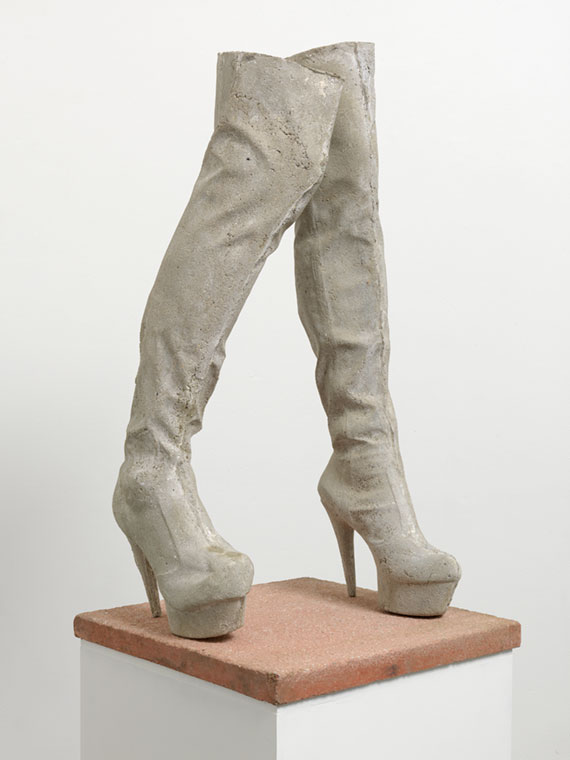

Elf Warrior is androgynous. In terms of the more clearly feminine Bunnies however, yes, they seem more exuberant and confident right now. And of course, there’s no reason why women shouldn’t revel in their sexuality. Or why high-powered women, politicians, CEOs, media stars shouldn’t totter around in high heels with a pancake mask on either, for that matter. That’s just the way it is. Or seems to be.

I think the use of colour in the recent Bunnies is a bit like they’ve started to use make-up.

You work with a vast range of media and materials in a non-hierarchical yet precise way. You’re now working with bronze, which has such art-historical gravitas. Can you describe how the turn to bronze came about?

I made a few early forays into using bronze and other metals. Small things – a cast of bollocks, a beer can penis. I’ve been open about materials and the values ascribed to them. I certainly don’t think that a sculpture is better or has more gravitas for being made out of precious metal. Quite the contrary a lot of the time. I’d take a concrete cube over a bronze one any day of the week, personally. Nor do I see why any material should be off limits.

Materials all mean something in themselves. As do gestures, make-up, body augmentation, what we wear – collars come to mind, all the little affectations, all the blunt onslaughts. The Jimmy Choo heels versus the steel toe-cap Doc Martens.

I was prompted to make a set of six NUDS/Bunnies in bronze when I was invited to exhibit in the Garden of Carlo Scarpa during the 2013 Venice Biennale. I needed work that could cope with being exposed to the elements, so bronze was an ideal choice. Since then, I’ve developed it in terms of introducing other materials into the process, different metals, concrete. Also, colour. Occasionally going larger in scale, particularly for outdoor sculptures. It opened the door to a lot of new possibilities.

Turning to the body casts of your friends (collectively titled Muses) with cigarettes poking out of their genitalia, they feel like quite intimate and sincere portraits. Do you see them as collaborations? What does working collaboratively bring to your practice?

Yes, I do see them as collaborations. Being friends is collaboration. Making art, putting on exhibitions. Living in the world is a collaboration too.

They were very intimate to make. Each woman chose from a selection of furniture that I had gathered – a couple of chairs, a desk, a toilet or two. Items fairly typical of my practice over the years, that I wanted represented within the show of new work. Each woman assumed a position they were comfortable with – in terms of exposure that is. Nobody was very comfortable during the casting process itself, which takes about an hour when things go well. Longer if there are mishaps.

Four of the women also assisted me during the process of casting from the body, and making the eventual sculptures.

Sarah, what’s motivating you these days? Is it materials and techniques, things you’re reading, external politics or something closer to home?

I read a lot. All sorts of stuff. It can be a form of escapism; I’m often wanting to escape. Years ago, in another interview, I described art making as an “escape from Alcatraz.” That was to illustrate the need to be creative with whatever is on hand, applying whatever you have to the problem that needs solving – however longwinded or flippant the process might therefore be. Taking a nail file to an iron bar or throwing a rock.

I’m reading a lot of stuff that makes me want to escape too. I’d recommend two of them; one I’ve just finished, the other I’m halfway through.

This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends (2021) by Nicole Perlroth. It’s about the cyber weapons arms race. And The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (2018) by Shoshana Zuboff – for anyone who would like to try and grasp just how vulnerable we are these days.

They’re pretty heavy tomes. For those who feel unable to take them on, I’d recommend 12 Bytes: How Artificial Intelligence Will Change the Way We Live and Love (2021) by Jeanette Winterson. In fact, she recommends the surveillance book and many other good ones in her bibliography.

Reflecting on your status as a veteran in the field, does it feel strange to consider yourself in these terms? The enduring relevance of your work is a hard thing for artists to maintain.

I’m not reflecting on it much. Most of the time I’m just me in my normal life. I love to be at home. I like domestic things – cooking, spending time in the garden. I like hanging out with friends. Rummaging in junk shops and book shops. Driving about the country lanes. Dropping into the pub. I think the best thing success has conferred on me is that there’s a lot of room in my life for all these things. Interestingly, I saw all this clearly for the first time when I left school and looked at my prospects. Not that I’d be a successful artist, I had no idea about that, but that I wanted some room in my life, not to be always striving after bullshit. That seems to me the great luxury.

Well, that tough girl ‘fuck you, take this!’ attitude that characterised much of your early practice really resonated with me as a young woman. It was as if you gave women everywhere the permission and courage to just go for it. Sarah, what does it mean to you to be considered a feminist icon?

I’m often surprised by it. The world has moved on so much, these past 20 years especially, I’m surprised I’m not obsolete. I’m also surprised that these somewhat off-the-wall objects have that kind of reach. I was in China for the first time in 2019. I had no idea what to expect from such a foreign place. I was really moved by the reaction of young women there.

Sarah Lucas is represented by Sadie Coles HQ, London and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

sadiecoles.com

gladstonegallery.com

nga.gov.au

Image credit: Sarah Lucas, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996, from a portfolio of 12 iris prints, Self Portraits 1990 – 1998, 1999, iris print, 60 x 80 cm. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

Image credit: Sarah Lucas, Elf Warrior, 2018, bronze, concrete and cast iron, 183 x 77 x 88 cm. Photo: Steve Russell Studios. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

Image credit: Sarah Lucas, Jubilee, 2013, concrete, concrete paving slab, 85 x 44.5 x 44.5 cm. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 37 (Feb – April 2022).

Click here to Subscribe