Shireen Taweel: The Sacred and the Profane

Over a coffee in Darlinghurst on a sunny afternoon, Taweel, who has just returned from a residency at the Vermont Studio Center, spoke to VAULT about the pull of sacred geometry, the importance of creating space for ritual and the stories of migration that are written in the sky.

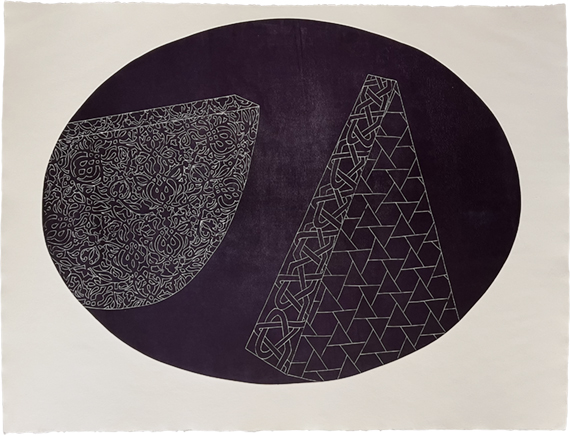

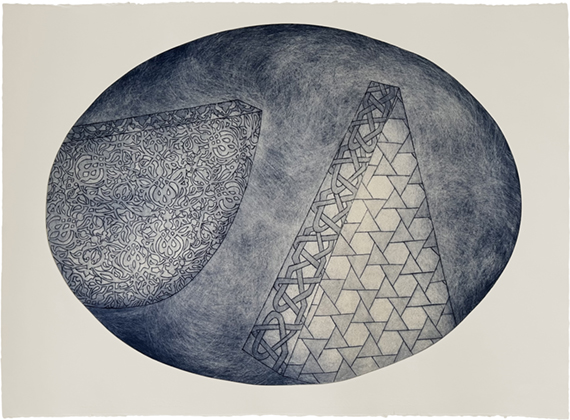

Image credit: Shireen Taweel, Astro architecture II, 2022, engraved copper plate, relief engraving, unique print, 55.0 x 75.0 cm

Shireen Taweel’s idea of the sacred isn’t distant or abstract. It pierces the surface of everyday life. As a child, the artist, who grew up between Western Sydney and the Northern Beaches, recalls marvelling at the interior of the Lakemba Mosque while colouring in verses at Arabic school. When she talks about copper, it’s with the reverence of someone who has apprenticed herself to a medium. “I am not allowed to have an ego,” says Taweel, who studied with coppersmiths in Gaziantep, Turkey. “It reminds me to listen to the material, be present with the work.”

Taweel draws on ancient techniques – hammering, carving, engraving – to realise installations, sculptures, drawings and prints that speak to heritage, knowledge and language. Her best works illuminate connections between our interior and exterior worlds, casting identity as an act of creation, always in flux.

You’ve long made work about the relationship between art, objects and architecture as well as the sacred geometry that is central to Islamic places of worship. We can see these early ideas in tomorrow, InshAllah, which showed at 55 Sydenham Road in 2016. How did that work come about?

A lot of my undergrad work looked at the internal architecture that we carry with us through experiences of migration. The phrase tomorrow, Inshallah comes from an expression of migrant’ hope: ‘Tomorrow will be better, God willing.’ It is the hope that we can build a better future from the circumstances we are in. That was a mantra my family had. I’ve always felt that I’ve lived that way. My sense of home is really fluid.

The exhibition was also my first engagement with the piercings and the light and the atmosphere of an artwork.

Migration really is a rupture!

That was the first time I left my sculptures very raw. Nothing was refined. I wanted to bring my studio processes directly into the installation space to share that experience. Those transformations are a time of significant growth. But they are also a vulnerable experience, quite painful.

Your installation tracing transcendence (2018–21), which is now on show as part of Making Worlds at Sydney Modern, was informed by the mosques in Broken Hill built by the Afghan cameleers who have been journeying through the outback since the mid-1800s. What were your hopes for it?

I only learned these histories in my adult life and I found that really frustrating, because I had such a turbulent youth during the 9/11 climate. I felt denied a sense of belonging here. It compelled me to bring that history into the public sphere and reflect on my community’s experience. The mosque is quite threatened in this environment – when there is a new mosque proposed, there is a lot of push back.

I was blown away by the humility of the cameleers and the incredible infrastructure they were able to build, even though they were not architects themselves. In Broken Hill, the mosque has a mihrab, a recess in the wall that indicates the qibla, the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca. Not only is this beautiful infrastructure built into this tin shed exterior, but they also lined the inside with pressed tin. There is a floral ceiling, an ornate carpet. I have never seen vernacular Australian materials used like that. I found their sense of the sacred so moving.

This cultural hybridity is a recurring theme in your work. I’m thinking of Switching Codes (2020–21), a series of copper sound sculptures and engraved copper tablets that explore the confluence of Arabic, French and English spoken in Lebanon. To me, it also reflects the ways in which migrants code-switch between different contexts to adapt. What sparked Switching Codes?

Switching Codes was very much about expressing how dynamic and rich languages are on this continent. In the Global South, you have so many languages in one household. The sound sculptures and tablets are about the fluidity of language and how it shifts between context, the old ancient lineage of codeswitching. I wanted to explore it in a way that was quite celebratory.

The situation in Lebanon is dire now, but the protests and uprisings were really fascinating. There was a really strong message of change, across so many different languages in one space. For me, the sound work was like a happening. It was dynamic, maybe even disorienting. There were many different languages and a lot of sound recordings from the protest. The sound sculptures themselves are very humanlike.

The seed of the work came from a long struggle in the Australian climate, and a desire to share the plurality of languages that my family speaks, which has always been denied. I’ve always grown up with hostility – never speaking Arabic in public spaces, only speaking English. It is so aggressive. It was very compelling for me to bring this into a public environment. To hold space for it.

The notion of holding space for connections to culture is a fixture of your art. For example, Shoe Bathers, your May 2022 installation at Firstdraft, draws from your family’s history of bathing at the Hammam al-Nouri in Tripoli …

For me, [art] is really about thinking through those communal and collective experiences. In the bathhouse, there is a sensuality. You are in light. You are in water. It is another form of sacred space and ritual. My family comes from Tripoli, from a very old part of the city and everyone in my family bathed there, including my mother’s generation.

I made all the olive oil soap, which spoke to olive oil soap production in Tripoli. I bathed with the soap too, so it was carved with my body. I wanted to share the architectural structure of the hammam. Over millennia, the marble softens and that talks to me about the movement of spaces and places. There is a sound work of me bathing. I wanted to include my aunt in that. My understanding of bathing and cleansing – on a physical and spiritual level – has been influenced by the matriarchy. How I learned to look after myself has always been through my aunt, through my mother. It’s about carving out spaces for those intergenerational experiences.

The last time we spoke, you were on residency at the Sydney Observatory, where you were using celestial navigation to explore the history of migration. Some of this new work will feature in your upcoming show at STATION, Sydney. What new direction has this opened up for you?

Celestial navigation [has] allowed humans to move across land and sea for millennia through the power of observation. [But] the picture of who is in space is so narrow. There were female astronomers in the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries. There was one woman, Mariam al Astrulabi, who advanced the astrolabe, an important device in terms of understanding the cosmos and the stars. I want to bring that cultural narrative into astronomy and research.

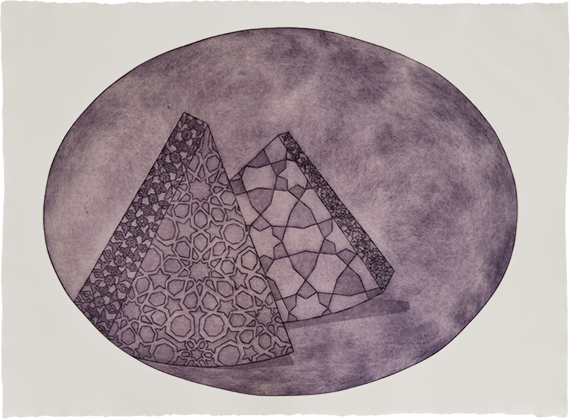

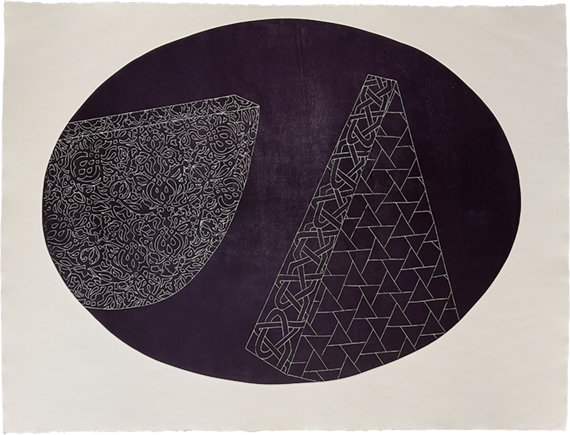

Our relationship to stars and space and the cosmos and the sacred is a continuation of this navigation. What would our culture look like in space? What type of mosques would evolve in space? A lot of [these ideas] are based on my research into these celestial instruments.

The STATION show is very much the first stage of a larger project. I’ve called it Sacred Architecture and the Celestial Body. I’ve decided to include a large drawing [I made] at the Observatory, as well as a series of prints that show astro-architecture and a series of sculptures that talk to each other about sacred architecture in space. There are also circular forms directly based on instruments I’ve found. We are engaging with space now and in a sense, doing so quite irresponsibly. If we had more cultural practitioners at NASA, maybe we could shift that relationship. The colonial dominance of space has annihilated everyone else’s voices, so I’m trying to bring [them] back in.

Shireen Taweel shows at STATION, Sydney from January 21 to February 11, 2023.

stationgallery.com.au

Image credit: Shireen Taweel, Astro architecture II, 2022, engraved copper plate, aquatint print, unique print 55.0 x 75.0 cm.

Image credit: Shireen Taweel in her printmaking studio, 2022 while on residency at the Vermont Studio Centre, USA Photo: Ann Ginsburgh Hofkin Courtesy the artist and STATION

Image credit: Shireen Taweel, Astro architecture I, 2022 engraved copper plate aquatint print, unique print 55.0 x 75.0 cm

Image credit: Shireen Taweel, Astro architecture II, 2022 engraved copper plate aquatint print unique print, 55.0 x 75.0 cm

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 41 (Feb – Apr).

Click here to Subscribe