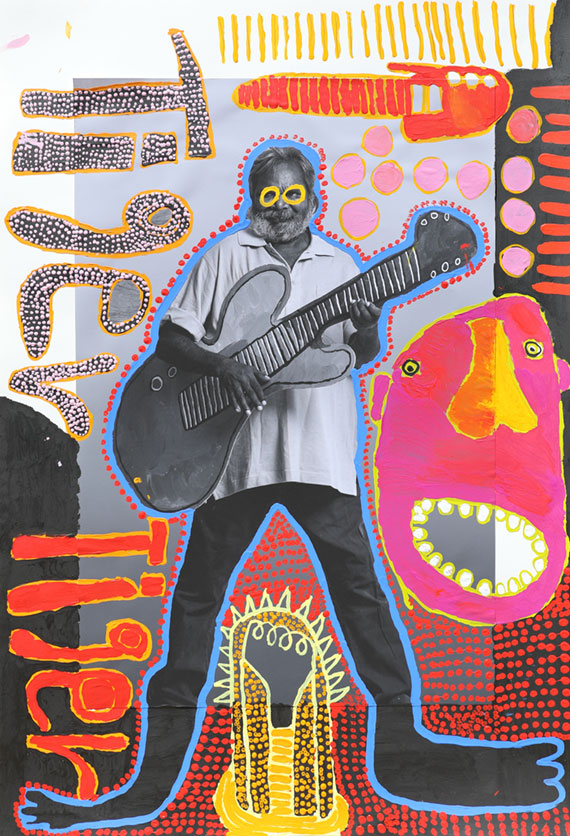

Highway to Tiger: Tiger Yaltangki

In vivid colour and dynamic compositions combining references to popular culture with his Anangu culture, Yankunytjatjara artist Tiger Yaltangki exudes the voice of a rock ‘n’ roll star.

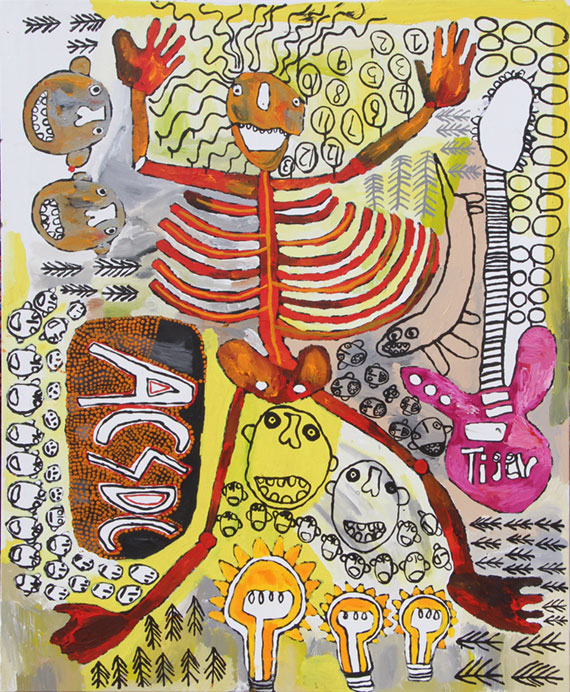

Image credit: Tiger Yaltangki, Malpa Wiru (Good Friends), 2023, synthetic polymer paint on digital print and paper, 76 x 112 cm. Courtesy Alcaston Gallery © The Artist, Iwantja Arts and Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne 2023.

In one of AC/DC’s most-loved tracks, ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Singer’, Bon Scott famously sang: “Gonna be a rock ‘n’ roll singer / I’m gonna be a rock ‘n’ roll star.” It’s a rebellious and determined sentiment that eschews moral and social standards in favour of a life of self-expression, authenticity and adventure, captured in the simplest of terms: rock ‘n’ roll star. For Yankunytjatjara artist Tiger Yaltangki, this music – along with that of bands such as Creedence Clearwater Revival, Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd – drives his artistic practice, manifesting in paintings, drawings and mixed media works that reference both popular culture and that of his Aṉangu people.

Yaltangki lives in Indulkana community on Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, where he has been working at the Indigenous-owned and governed Iwantja Arts since 2007. Predominantly non-verbal, Yaltangki is a prolific painter and a compulsive drawer. His works are vibrant, colourful and dynamic, combining handwritten band names, lively figures, guitars and refashioned lyrics like “Highway to Tiger” with depictions of Mamu – Aṉangu spirit beings that are scary to some, but for Yaltangki bring a benevolent, if mischievous, charisma. Iwantja Arts coordinator Heath Aarons says Yaltangki has produced thousands of canvasses across his career and will often draw on any surface available to him in lieu of a readied canvas. “He works really fast, and you can see the energy in the works,” Aarons explains. Aarons also tells me that since he acquired an old boom box, Yaltangki often works with rock music playing, sometimes even singing along – and that he obsessively collects cassette tapes.

While Yaltangki’s works are typically quite large, more recently he has been creating smaller-scale works using found AC/DC posters from the ’ 80s and ’90s, which he collages onto paper and works back into with paint. He embellishes the outline of the band members’ faces and figures with dots, lines and circles, emphasising the attitude in their stances or expressions and further glorifying their god-like status. These are paintings of worship. In one piece, a bare-chested Scott flashes his gold-buckled belt, microphone cord draped through his fingers and pure energy radiating out of him in the form of Yaltangki’s red and orange dots and circles. In another, larger white ovals bordered with orange spots appear like dressing room lights around the blackened canvas edge, while in the centre an image of Scott, long hair blown back, is plastered with the iconic AC/DC logo. Yaltangki has inserted the words INDULKANA and TIGER just below the image, elevating himself to rock star status. There is reverence here, yes, but this is Yaltangki’s world – Bon Scott is just living in it.

Iterations and expansions of these works will be shown in numerous major exhibitions across 2023. In Melbourne, Yaltangki has an upcoming solo show with his longstanding gallery, Beverly Knight’s Alcaston Gallery, and a largescale installation with the festival RISING – both opening in June. In October, he’ll present a solo showcase at the Art Gallery of South Australia’s (AGSA) Tarnanthi Festival.

Both the Alcaston and Tarnanthi exhibitions will contain a number of these collaged works, some of which – for the first time – contain photographs of the artist himself. Artistic director of Tarnanthi and curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at AGSA, Nici Cumpston, says that in positioning himself and references to his people next to these iconic band posters, Yaltangki “brings his community and himself in on the scene.” As she explains, “They’re posters, so it’s as if, you know, he’s the rock star now.”

Like the music it references, Yaltangki’s work is infused with rhythm. Various markings and motifs – lightbulbs, arrows, wavy lines – overlap, intersect and weave into rather masterful compositions which, despite his instinctive, repetitious approach, achieve a seemingly effortless freshness and spontaneity. He is confident with neon greens, bright reds and electric blues. Heads are flipped upside down and guitars soar, lifted up by figures that are amalgamations of Mamu, family, friends, television characters, rock stars and self. In some pieces, clustered numerals count up from one, as if tapping out a tempo. “He is playing that music through the numbers,” Cumpston says. “His work has a beat, it’s got rhythm, and it’s all about that mark making. It’s active, it’s alive.”

It is well-known that Yaltangki’s interest in art grew out of a daily ritual of painting his Akubra hat and boots, using acrylics from Iwantja. Yaltangki was encouraged to start painting by Indulkana cultural leaders such as Alec Baker, one of the art centre’s founding painters, and started exhibiting just three years later in 2010. Since then, he’s become a five-time finalist in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (2013–16 and 2018) and has exhibited widely across Australia and in the US, including in New York City.

Knight, who established Alcaston Gallery in 1989, first exhibited Yaltangki’s work in 2016. She is almost overcome recalling that first exhibition, at which he was joined by Iwantja trailblazer and close mentor Vincent Namatjira. “It was enlightening,” she says. “He was so happy, he was humming. There were tears streaming down people’s faces. It was emotional. There are exhibitions that look incredible, and people can see the work in their houses, but this was different. Tiger was different.”

Like Namatjira, whose work is famously political and witty, Yaltangki is part of a generation of First Nations artists who are working outside of traditional norms and who paint, as Knight says, “what they think more than what they see.” These are worlds as seen from the “third eye part of the brain” – imaginary, magical, but no less real. They are enlivened, heightened versions of their diverse worldly experiences. While Namatjira jibes at the absurdity of the colony, stripping figures of supposed power and influence back to bare their hypocrisy, Yaltangki’s veneration of pop culture icons – often elevated through a deceptively white version of ‘Australiana’ mythology – strikes as an act of personal reclamation. In this way, Yaltangki’s work is both highly personal and also firmly positioned within global dialogues about contemporary identities.

Knight says the painterly quality of Yaltangki’s work is constantly developing. She is excited to show every new body of work, each one more confident, more boldly idiosyncratic than the last. At the same time, the work has maintained a potent simplicity. “He’s thinking about a lot of things, and he can’t talk to you about them, so in his way he is putting them down on paper. He’s telling you: this is me, this is my story.” She credits a lot of Yaltangki’s success to the support he enjoys at Iwantja, where he has been able to freely explore his artistic potential and capitalise on growing interest in his work.

Currently, Yaltangki is undertaking a significant expansion of his practice for an immersive installation at RISING: in Melbourne, commissioned by curator Kimberley Moulton for the festival’s headline group exhibition, Shadow Spirit. The exhibition will transform an old ballroom and 12 large rooms on the top floor of Flinders Street Station into a celestial realm weaving together the different spirit-world connections of 15 First Nations artists. Yaltangki is collaborating with Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara musician Jeremy Whiskey to create the aptly titled Rock ‘n’ Roll, an installation combining largescale painted sculpture with a screen and sound work. Moulton says that Yaltangki and Whiskey have a strong relationship, bound by their shared appreciation for the music that empowers and excites them. “Seeing them work together in the recording studio, Jeremy just ripping the guitar … it’s pretty special.”

Within Shadow Spirit, as in the spirit world itself, Moulton says, “there are light moments and there are dark moments.” Where some stories presented in the exhibition contain old, enduring wisdom, maybe heeding warning or offering protection, Tiger’s work brings spirits of Country into direct conversation with contemporary culture in vivid colour. “Having Tiger’s work was important because it provides an interesting entry point for people to understand his culture and experience, and to provide a moment of lightness and humour,” she explains. “There is a nostalgia to AC/DC that I think most Australians can tap into, and music itself is a common language that Indigenous people can connect to strongly. They know how music can inspire and energise, or ‘re-spirit’, you.”

This is perhaps what is so powerful about Yaltangki’s work: through music, his pure artistic essence is stirred up and made plain on canvas and paper. Painting has enabled him to have a voice, to be a rock ‘n’ roll singer. It is cathartic and honest. As Knight simply states: “He is telling you about himself, what he loves and what’s important to him.” In doing so, he is also showing us all how we might discover what’s important: through listening in, and letting simple truths flow out.

Tiger Yaltagki is showing in Shadow Spirit as part of RISING, Melbourne from June 7–18, 2023 and in Tarnanthi Festival at Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide from October 20, 2023 to January 2024.

rising.melbourne

agsa.sa.gov.au

Tiger Yaltangki is represented by Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne.

alcastongallery.com.au

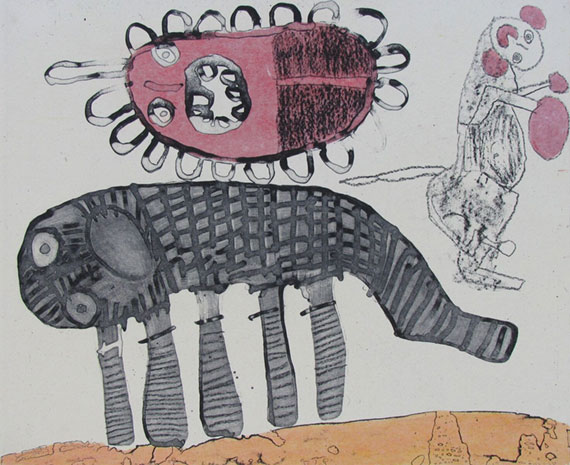

Image credit: Tiger Yaltangki, Malpa Wiru (Good Friends), 2018, etching with Chine Colle, 39 x 47 cm. Courtesy Alcaston Gallery © The Artist, Iwantja Arts and Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne 2022

Image credit: Tiger Yaltangki, Malpa Wiru (Good Friends), 2018, etching with Chine Colle, 39 x 47 cm. Courtesy Alcaston, Malpa Wiru (Good Friends), 2022, synthetic polymer paint on linen, 152 x 122 cm. Courtesy Alcaston Gallery © The Artist, Iwantja Arts and Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne 2022

This article was originally published in VAULT Magazine Issue 42 (May – Jul).

Click here to Subscribe